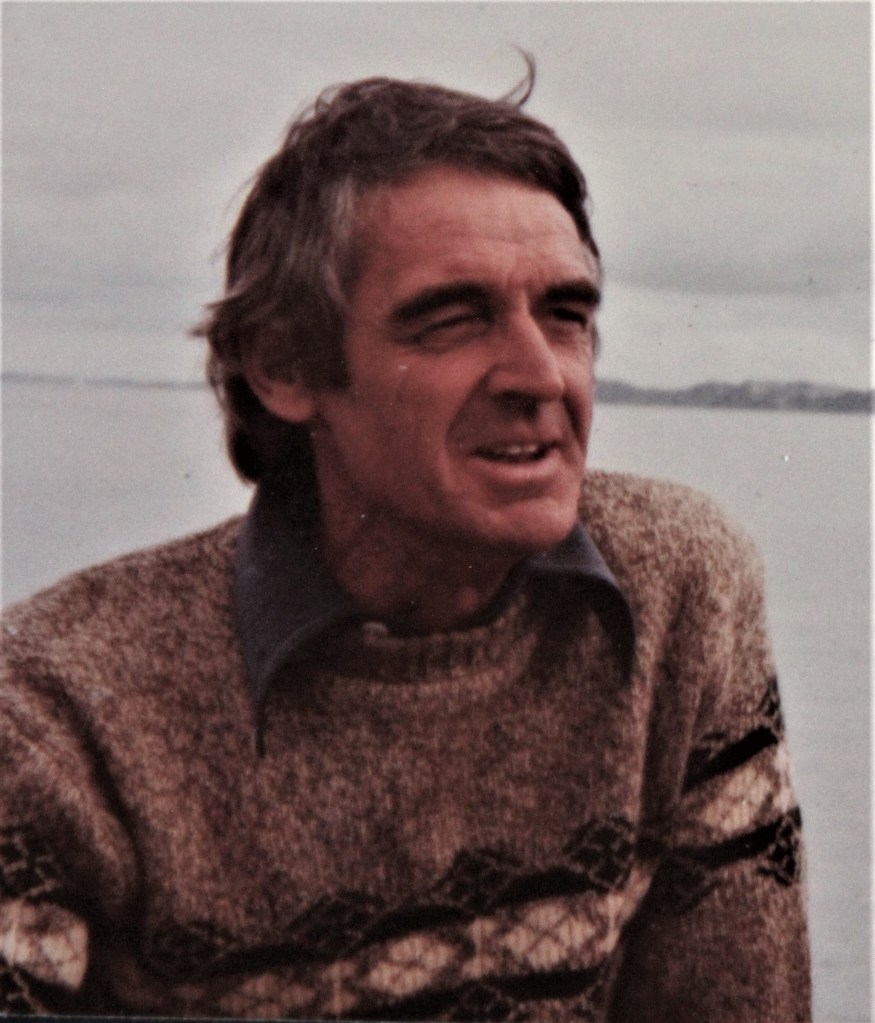

John’s Personal History

A happy Auckland childhood

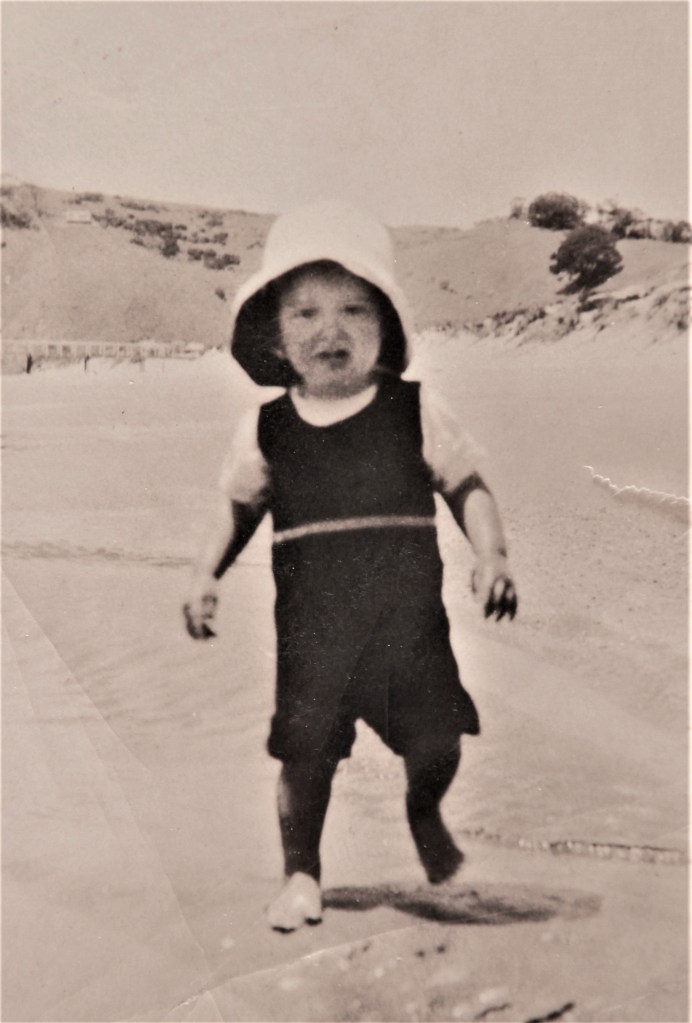

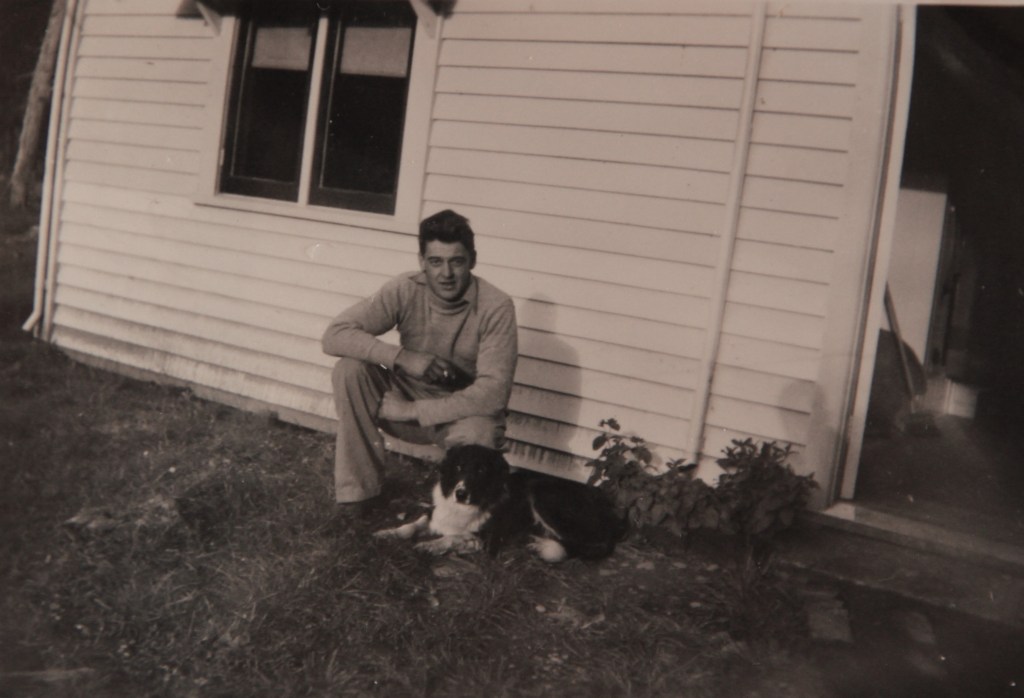

My father was born into a moderately well-off Auckland family on the 15th of August 1926. His parents were relatively newly married – first marriage for his mother and second for his father – and he was the first of what was to become a family of four children. They lived in what was then, a relatively substantial house in Exeter Road in Mount Albert, Auckland. His father was an accountant, and his mother a stay-at-home mum.

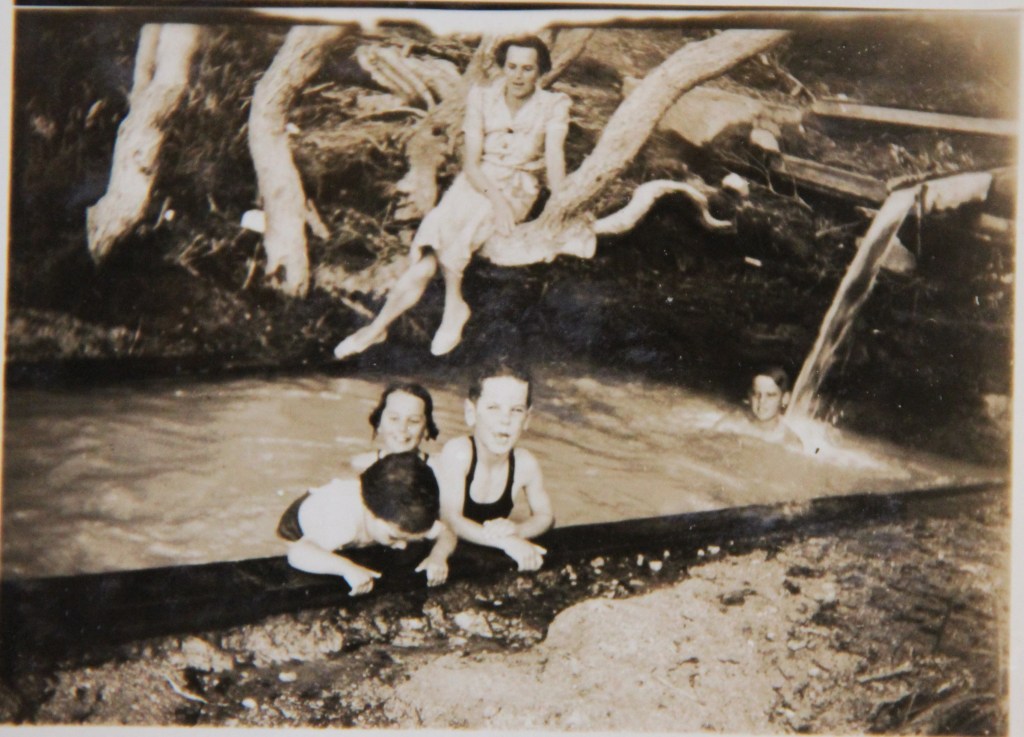

He claimed to have had a good childhood, and although he never said as much, I feel sure he was well-loved by his parents. Although he never spoke unkindly of his father, he had little in common with him and was largely left to pursue his own interests. Family holidays are strongly featured in his childhood memories. They were usually with his mother’s family and in places like Onetangi on Waiheke, Tindalls beach on the Whangaparāoa, Cornwallis with his older half-sister Peggy, and Lake Rotoiti. Other influential experiences included the times he spent on his aunt and uncle Kathleen and Arthur’s farm at Mauku in south Auckland, and time with another aunt and uncle, Mary and Harold, and their two daughters who were around his age and who he was very close to. Harold also had a launch, which was a great attraction for a boy with a growing interest in the sea.

So, although born a city boy, he was exposed very early, to a rural life and to boats, beaches and the sea. He also travelled more than many children did at the time.

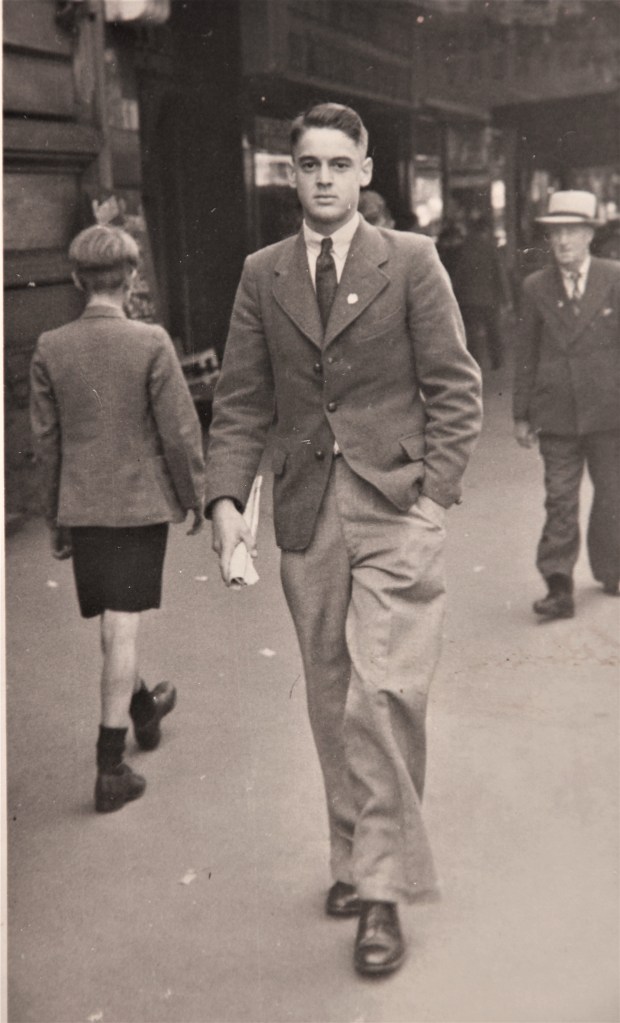

He went to Mount Albert Primary and high school at Auckland Grammar and claimed not to have liked it much. Despite this, he did moderately well academically and became a very good gymnast, representing Auckland Grammar. He also played hockey, and in his last year there, he received his ‘colours’ as a rep. hockey player for Auckland Grammar. Not being socially gregarious, he didn’t have a wide group of friends at school, so he didn’t take full advantage of the Grammar ‘old boys’ network’ in furthering his career.

In the time after the 1929-33 Great Depression, his father’s business ventures were doing very well (unlike his son, he was taking full advantage of his connections in the Auckland business community), so, around 1937, his father built a large house at 54 Selwyn Avenue in Mission Bay. He also bought a beach-front section at Tindalls Beach next to a section and bach owned by his brother and sister-in-law Harold and Mary Taylor. Dad loved both these places; Selwyn Ave with its easy access to the beach and ample space to house the growing family, and Tindalls for the camping holidays and pottering around in boats. The family lived at Selwyn Ave for the remainder of his teenage years.

Preparing for a career in agriculture

In 1943, the war in Europe was coming to an end, and as a very young sixteen-year-old, Dad was contemplating his future. Instead of waiting to qualify for the armed services draft, he enrolled in a Diploma of Agriculture course at Massey College. This precluded the need for him to begin training for the armed services when he reached seventeen, as it was providing training for an essential service – agriculture. For him, this was an obvious choice. While not a pacifist, the requirement to surrender self-determination and to follow all orders without question would have killed him long before any enemy gunfire.

Unlike school, he loved his training at Massey. It exposed him to knowledge that interested him, and it confirmed his plan to pursue a career in agriculture. As was required for his diploma course, he worked on several farms over the next four years.

The first was a farm in Southland and his first task there was to clean out the whare he was to live in. This was being used as a chook house, so he had to evict the hens and clean out chicken shit before he could set up his ‘home’. He told of coming in for breakfast after milking the cows to find his porridge in a plate above the Arga, cold with a thick skin on it, and of finding his mid day dinner of roast in the same place – cold with the meat fly blown. It tells something of farmer attitudes to staff at the time and partly explains why he ended up in Kew Hospital in Invercargill with hepatitis. A friend took him off to Stewart Island to recover, but this illness was to affect his health for many years to come. He worked on three steep North Island hill country farms; at Taoroa, east of Taihape; a farm in the Pohangina Valley on the western slopes of the Ruahine Range; and Hauturu, a farm south-east of the Kawhia Harbour. They were all in their development phase, and Hauturu in particular appeared to be hard and challenging country. Here, he lived in what looked like an old, abandoned house that he said was completely bare when he moved in, but for a bed. Apple boxes sufficed for storage and sacking covered broken windows. Soon after he moved in, his mother wrote and asked if she could send him anything to make his lodgings more comfortable. With dry irony that she completely missed, he replied, “Thanks Mum, but I have everything I need except perhaps some picture hooks for my paintings.” She duly sent him some picture hooks.

He also worked on an extensive pastoral property in the upper end of the Maniatoto known as The Styx. The latter was farmed by Laurie and Marge Falconer, friends of Charlie and Dorothy Aitchison, and their daughter Beverly who was later to become his wife. Laurie had a reputation as a hard man to work for and had gone through a number of shepherds who had only brief stays on his farm, but Dad and Laurie got on very well to everyone’s surprise.

He was also to later work on an arable property at Waihao Downs in the lower Hakataramea Valley, a place that kept him moderately close to the Maniatoto.

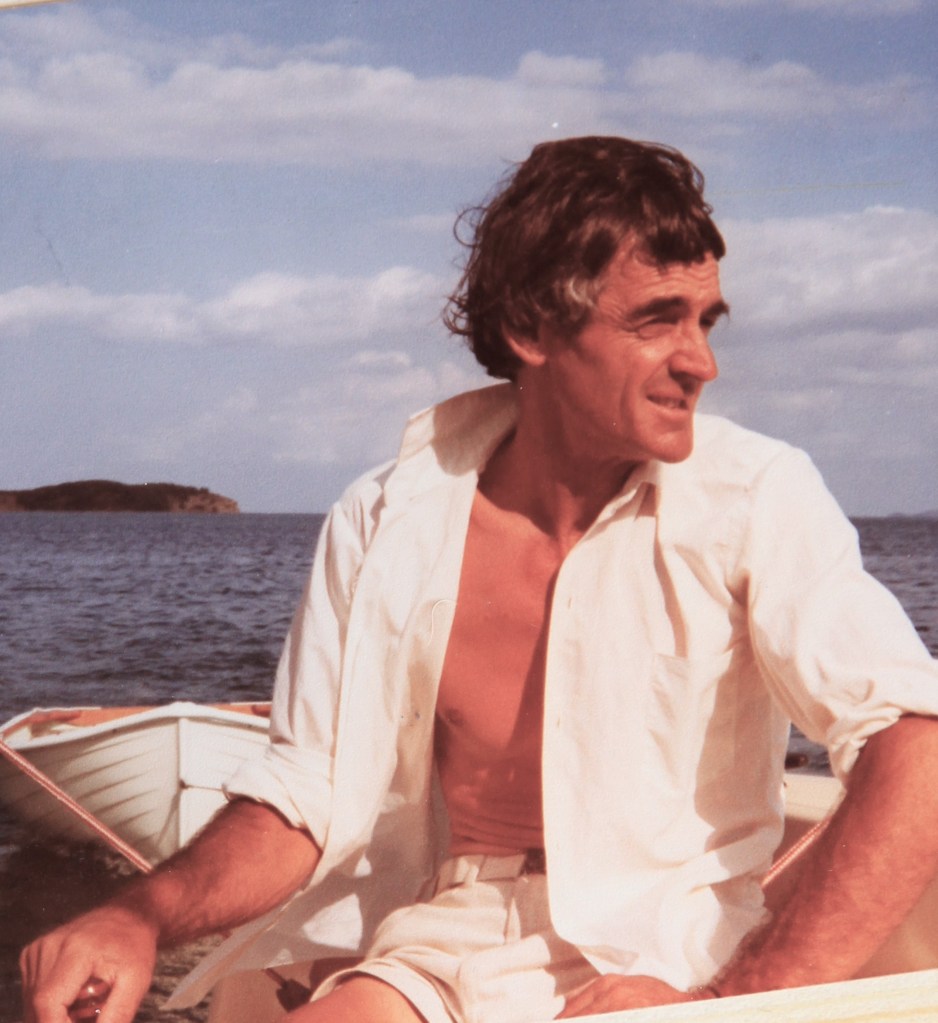

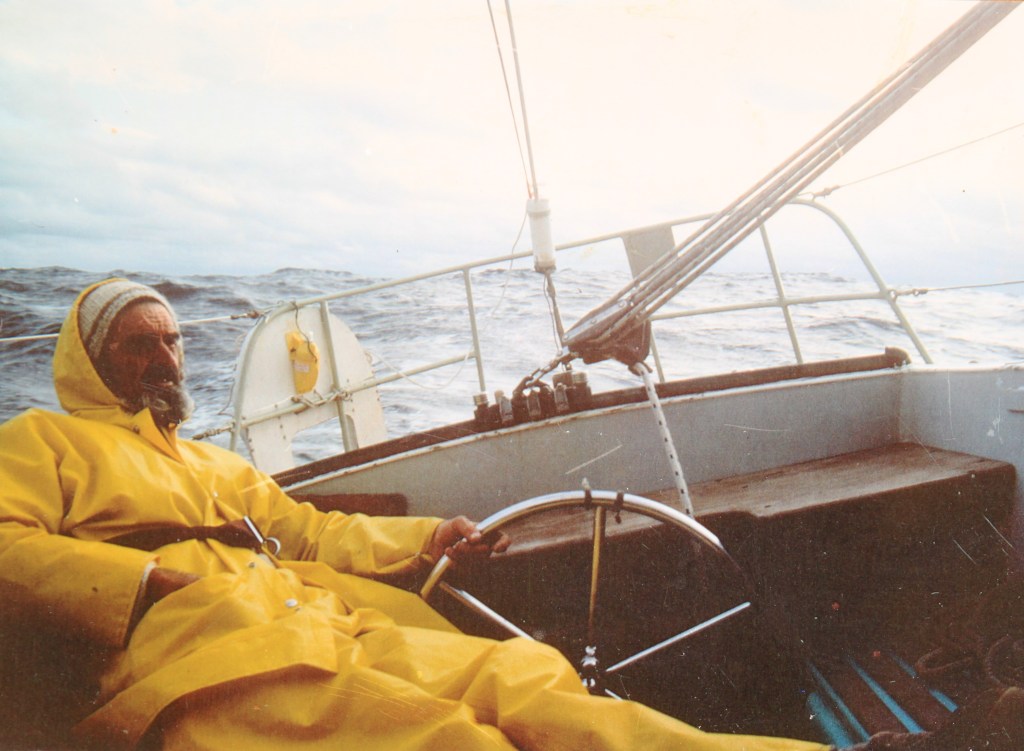

The paradox and ‘the human situation’

My father inherited the same restlessness and energy that was common in many of his ancestors (he could spend days at an anchorage waiting out some bad weather or away at sea and be constantly on the move). He shared with them an active mind and curiosity, and like them, he seemed to need a mission in life – a purpose beyond raising a family and building a comfortable life. While he lacked the inclination to simply make money, build a business or become a leader in his community, he was intellectually capable of conceiving a purpose, investigating it and putting together a plan that would achieve it. He did, then, have many projects and plans, and many of these required some courage to implement – like sailing the Pacific. He did not walk a well-trod path and never felt he had to conform to convention, so his plans often came as a surprise to many who knew him.

He was also a cautious man who liked certainty in his life. Unlike Mum, he could not cope with an adventure predicated on, say, following a yellow car to see where it would take him. He wanted to know what the plan was, where they would go and how much time it would take. He was, therefore, a meticulous planner, and he applied risk mitigation strategies long before they became fashionable in business. Grandson Richard tells the story of Grampa giving him a useful dictum for future use when planning for a trip – “Piss poor planning always leads to poor performance”.

So, that was the paradox in the man. Conservative and cautious on the one hand and, on the other, apt to venture into schemes and plans that were unconventional and consequently involved considerable risk and uncertainty.

He never let his cautious nature or need for certainty prevent him from doing things, but for all his energy and all his schemes and ventures, there was never a point where he settled on some grand plan or when he felt he’d achieved his purpose in life.

He was further toward the conceptual thinking end of the spectrum than Mum. He thought much about what he called ‘the human situation’ and about environmental issues. He was not a religious man, so he was not happy to surrender to complex issues and leave them in the hands of God to fix. However, neither was he a political animal. He didn’t have sufficient confidence to foist his opinions on others – he was too ready to accept that he might be wrong. Having said that, he shared his ancestors’ propensity to reach for the pen whenever he felt strongly about something clearly within his knowledge and expertise. Some of his musings in his ‘Little Red Book’ reflect this tussle with this human situation’:

“Understanding the complexity of the human situation is confounded by the fact that smart cookies don’t recognise any complexity which occurs beyond their understanding and their ability to cope.

“To even begin to understand the human situation one needs to at least mentally surrender one’s own (comfortable) situation.

“It’s a bit much to expect that ecological processes should cease just because human beings have become civilised.

“To attain ultimate wisdom, one must reconcile humanity’s intellectual and technological superiority, with the absolute necessity for us to have regard for our place on earth as simply another species of animal. For some, this wisdom rests only with God, and they’re happy to leave things in his hands. I know it is hard to move the common attitudes even slightly, but we must try surely. There just must be a guiding hand for goodness’ sake!”1

JH Murray. ‘Thoughts of Mine – The Little Red Notebook’

He’d mostly seek to ‘reconcile’ the world’s social and environmental challenges in his own head. The problem was that he saw all the complexity and would often get lost in it all. As he couldn’t handle ambiguity and because he was always trying to reconcile the irreconcilable, he never quite landed on the answer. Toward the end of his life, he thought that maybe he had:

“My oh my! You just get a few ideas together and you find your time is up!“

However, even then, I’m not sure he really felt he had the answer to the human situation, let alone how it might be improved.

Having said that, he achieved a quality of life that was the envy of many. He always remained true to his values – good experiences, a relatively light touch on the environment, and less dependence on material possessions – and in this respect, he was ahead of his time. Perhaps this was the answer to ‘the human situation’; maybe this is a lesson he gave those who must face life in a post-carbon economy.

A romantic in the clasical sense

He was, in essence, a romantic in the classical sense – he focused on individual experience; he had a strong sense for the natural environment; he revered women; and he was very happy in his own company. He also had a tendency toward melancholy. His story about the girl and the gannet reflects his romantic ideals about life and experiences:

“A girl from a yacht rows a dinghy across the cove, and a gannet dives for his (or her) dinner, not ten metres off her beam. She stopped rowing and witnessed this simple natural event – the froth, foam and bubbles as the bird dived and then the emergence of this immaculate bird with prey in its beak. While this happens, the gannet’s dominance of the scene is absolute. She may not just now, know that she is privileged, this lass in the dinghy, but for sure she’s been inoculated, and its effects will be for a lifetime.“

While Dad delved into the abstract often, both he and Mum were experiential people – Mum more so than Dad. They noticed the details in the world around them, and they enjoyed the feel of a new place, a new scene or a new activity. However, where Mum would enjoy a scene for what it was, and her curiosity would have her investigate its context and history, Dad would see both the scene and its historical context as one. Their respective reactions to the Isle of Skye demonstrated this difference well. Mum just saw the brooding landscape and acknowledged its beauty. She was curious about its history, but that wasn’t part of what she saw. Dad saw not just a landscape but also the processes that created it, both physical and cultural, which together formed a different picture from the one that Mum saw. As Mum noted, he got it. She did not.

His own man

He was the antithesis of his father. My grandfather was, if not an extravert, a social being for whom position and status within his community were paramount. My father was an introvert who was very much at home in his own company or with a small group of friends, and he was never greatly interested in what others thought of him. Grandpa was competitive, a good sportsman, and a team player, playing cricket, hockey and later golf. Dad was a very good athlete, representing Auckland Grammar in gymnastics and hockey and Massey College in hockey. Still, he was not competitive and preferred individual pursuits where he could challenge himself. Grandpa did not inherit the interest in farming that was so prevalent in his great uncles (in fact, neither did his father or grandfather), whereas Dad had a deep love for the land, was a natural stockman, and was an innovative and capable farmer. Dad also had a deep love for the sea, which Grandpa did not seem to share.

This must have very much shaped the person that he was. From an early age, he wanted to shape his own future, and as his father could not be the role model that perhaps Dad sought, he found these in other members of the family. His uncle Harold Taylor was hugely influential in shaping his knowledge and love for the sea, taking him on boating holidays with his daughters Joselyn (Jossie) and June. Also, his aunt Kathleen and, to a lesser extent, his uncle Arthur Hill exposed him to a farming life on their farm at Mauku. Holidays here must have helped shape his interest and love for the land and for agriculture.

For all his differences from his father, he shared the same belief in what was right and proper. He felt there were certain codes of behaviour that people should uphold and while he did not seek social status for himself, he was conscious and even proud of his family history, and he felt a certain obligation to uphold the family belief in its position as honourable and respectable members of the community.

Because of this behavioural code, he was often labelled as a gentleman. He was invariably courteous, polite and respectful of others. He would take people at face value and trust that they were as they professed themselves to be. It was not that he was naïve or overly trusting, but he was slow to judgment and preferred to give people the benefit of the doubt. Peggy Slater, a friend of Mum and Dad’s from Los Angeles told me once that she could not believe the trust they had bestowed on her when they asked her to sell their yacht Cecilene on their behalf (Peggy was a yacht broker). Her first thought was that it was some sort of scam – no one could be so trusting. She thought then perhaps it was naivety but came to understand that they were simply trusting that she would do as she had promised. With that, she felt an obligation to satisfy her client like she had never felt before.

Although he couldn’t have been described as a feminist in the strictest sense, he did adhere to many of the basic tenets of feminism. He related to women better than he did to men, perhaps because with women, he didn’t feel the expectation from them to compete. For whatever reason, he was always much happier sharing his thoughts with women than he was with men.

“I have tremendous admiration for the Cindys* of this world, those young, healthy, confident women who, without alienating their peers in this sophisticated era, nor demeaning themselves in any way, live by a timeless and simple code of being themselves. They must surely represent the new and an effective aristocracy.“

JH Murray. ‘Thoughts of Mine – ‘The Little Red Notebook’

*(I have no idea who Cindy was)

Dad lacked the skills to read a room and to do small talk, so he tended to avoid these situations if he could and often looked uncomfortable if he couldn’t. He could, though, ‘talk the leg off an iron pot’ if given the right subject and audience. I recall many occasions when he would use his family as the audience for sharing his thoughts. I have a vivid image of Dad rolling breadcrumbs around the dinner table (he liked to have some dry bread with his meal) while he pontificated on whatever subject was currently on his mind.

Anxiety and self-doubt

I think he suffered much from anxiety at a time when this was not acknowledged or talked about. He was not good at sharing his worries, especially with his children, so he tended to go quiet and bottle them up. He was, however, self-aware enough to recognise this, which he reflects in his ‘Little Red Book’:

“I knew full well that I didn’t get the best out of many experiences or projects, or a whole era for that matter. Maybe because I was nervous or diffident or timid or whatever.

“I’m sad that I didn’t have the confidence to pursue a course of farming [at Kaharoa] and be prepared to live beyond the resources of an uneconomic unit without worrying about it to the point of illness.”

JH Murray. ‘Thoughts of Mine – ‘The Little Red Notebook’

(Later, in 1989, he recanted on this: “Heavens! How fortunate we were to have moved on.”).

It is likely that his nervousness and anxiety (he was certainly not timid) did act as a break on some of his plans, probably for the better, and it was undoubtedly true that his worrying did lead to ill health. However, I think he was being a bit hard on himself. He almost acknowledges this in another piece he wrote:

“Someone once told me that I was an escapist, presumably because I ventured into new areas of interest and endeavour. I hadn’t the whit in those days to realise that the biggest escapists are those in a position of utmost serenity, like work horses with blinkers on – seeing only what is in front of them and on a predetermined path, and not being brave enough to step off.“

JH Murray. ‘Thoughts of Mine – ‘The Little Red Notebook’

One exception to his unwillingness to share his worries was when, in 1989, Mum decided to go off to Europe on her own after he refused to go. Two months into her absence and after several letters suggesting that she was having a ball, he decided that he had lost her. He was quite beside himself and unburdened his fears onto his children. We eventually persuaded him to join her, and of course, when he got there, he found out he hadn’t.

Cleanliness

He was always quite particular about cleanliness and his personal appearance. He mostly wore the farmer’s uniform – check shirts and the like, and his clothes weren’t exactly fashionable, at least in later years, but they had to be clean and tidy. The elegance Mum described in him could make even the most ordinary clothes look respectable. Morning routines of washing and shaving would occur regardless of whether he was at home, cramped up in a tiny boat, or parked somewhere in a campervan, and shoes were always spotless.

Even in the hour before his death, drugged up with morphine and barely conscious, he was worried about making a mess. I recall him once yelling at me after he decided I’d been to the toilet and had not washed my hands. He was standing in the garden on the hill at Algies Bay as I was waiting for the school bus some half a kilometre away across the paddocks – “Get back here and wash your hands with hot soap and water”. I don’t recall whether I had washed my hands or not, but I was left in no doubt that these things were important to him.

Tradible skills

Two of Dad’s attributes that lent themselves to a farming life were his ability with his hands (which also served him well with boats) and his ability with animals. He could turn his hand to almost anything, and although the quality of his workmanship was not masterly (he felt that if a construction task couldn’t be done with a saw, a Sure-form blade, some screws, and epoxy resin, it was a task for someone else), it was always functional. He also had what farmers call good stock sense – he related well to animals and understood them implicitly – a quality he passed on to my sister Kay in spades. So, as an excellent handyman and stockman with a good grasp of the relationship between stock, fertility and the land’s inherent qualities, he was a very good farmer in his day, if not a good farm business manager.

Another attribute that perhaps didn’t serve him as well as it might was his sense of land and the forces that make it what it is and give it value. He had an unerring ability to hunt out good property, land that would serve the immediate purpose, but which would also have potential. Without exception, all the properties they bought, or that he found for others, were exceptionally good buys, and subsequent markets proved him right. He had a brief fling with being a real estate agent in the 1960s when he found a dairy farm for his brother and sister-in-law, Richard and Margaret, at Matakana. However, I don’t think he was cut out for the cut and thrust of that game, and his poor grasp of the monetary value of things did not serve him well.

A husband, father and community man

He took his perceived responsibility to provide for his family seriously and did exceptionally well regarding ‘experiences’. So, my childhood memories are full of happy trips away on various boats, camping at places like Matauri Bay and camping roadies around the East Cape and the South Island. Ironically, he didn’t come on this latter trip because he felt he needed to tend to our material needs by making some money selling fish on the side of the road at Orewa.

With Mum’s considerable support, he also adequately provided our material needs. While he recognised that material things were a necessary part of life, he had a poor sense of their monetary value and his interest in material possessions extended only to their utility. Even boats, which he loved with a passion, were not bought for their own sake but to serve a purpose, either fishing or family experiences.

Unlike Mum, who shared her father’s interest in cars, Dad saw them only as a means of getting from A to B. He once went off to town in the mid-1960s and, without consulting anyone, came home with a new Simca. It was a cheap and ugly French car that so embarrassed John A. that he refused to drive it and chose to stay with the old series II Land Rover. Dad was genuinely bemused that we could not share his enthusiasm for the bargain that he felt he’d got.

Although Dad would, if possible, avoid organised community events, he understood the importance of a cohesive community and the role that community service played in achieving this. The thought of joining something like Rotary was anathema to him, and he’d often say that it simply wasn’t him. But, after much angst, he did join Rotary in the mid-1960s, feeling that as a proprietor of a local Warkworth business, he should do his bit. This lasted about a year.

He and Mum between them took on several of their own community ‘beautification’ initiatives in the town over the years, cleaning up rubbish-covered banks and planting them up. One such place was the slope below the Stubb’s butcher shop on Wharf Road in Warkworth where they planted, among other things, a magnolia which is still there today. Another was the small spit of land in Sunny (Shark) Bay in Bon Accord Harbour, Kawau. Here, they cleaned up the weeds and planted pohutukawa and kowhai that they’d propagated themselves.

He also felt he should pass on his skills as a seaman and a navigator, so he was, for several years in the late 1960s, a tutor at the Mahurangi Polytech. He taught Launch Masters, Yacht Masters, and celestial navigation courses, often to his fellow fishermen who were increasingly being required to have these qualifications. Despite his social reticence, I think he enjoyed this, which is quite an irony as in my experience, he was a bloody awful teacher because he would always want to take over and do it himself.

As a father, he was always interested and supportive of what we did. While he was clearly pleased that I had pursued a career in agriculture and then natural resource management, he never pushed me in any particular direction. While he considered self-discipline important, he was rarely a disciplinarian. I recall getting the odd whack on the backside or clip on the ear as happened in those days, but mostly, he resorted to a firm word or often used his famous “black-eyed glare”. It could quell the staunchest child, and somehow, it could convey exactly what you had done wrong and what you needed to do to fix it. That is not to say that he didn’t have a quick temper. Anger could flare in an instant, but it was rare enough to always instil some shock. A hand crashing down on the table, salt, pepper, the milk jug, all leaping into the air when some miscreant child breached a code of decorum. This was usually around breaches of table manners (he was big on table manners) but could also include answering back or not showing sufficient parental respect. For all that, I was left in no doubt that he loved us all deeply, although he would never have used that word.

For obvious reasons, I’m not well qualified to describe him as a husband, but Mum wrote about why she loved her husband of nearly 50 years in ‘Message to Our Grandchildren’.

“There’s lots of reasons. He used to tease me by telling people I grabbed him in order to get out of the Maniatoto. This had some truth to it but there was much more. I loved the grace and precision with which he did everything. I told him sometimes that he moved like a black man, and I loved that in him.

“Early on in our life together, I think he set his sights on experiences and a search for wisdom rather than the material success sought by others. A tendency to experience a total change in personality sometimes gave rise to much strife, but he made progress in overcoming this in time.

“I knew always that I could count on his support, and he seemed always to accept my shortcomings as part of the package. We had spats about minor things, but he never ‘hit below the belt’. We seemed to have developed rules of warfare.

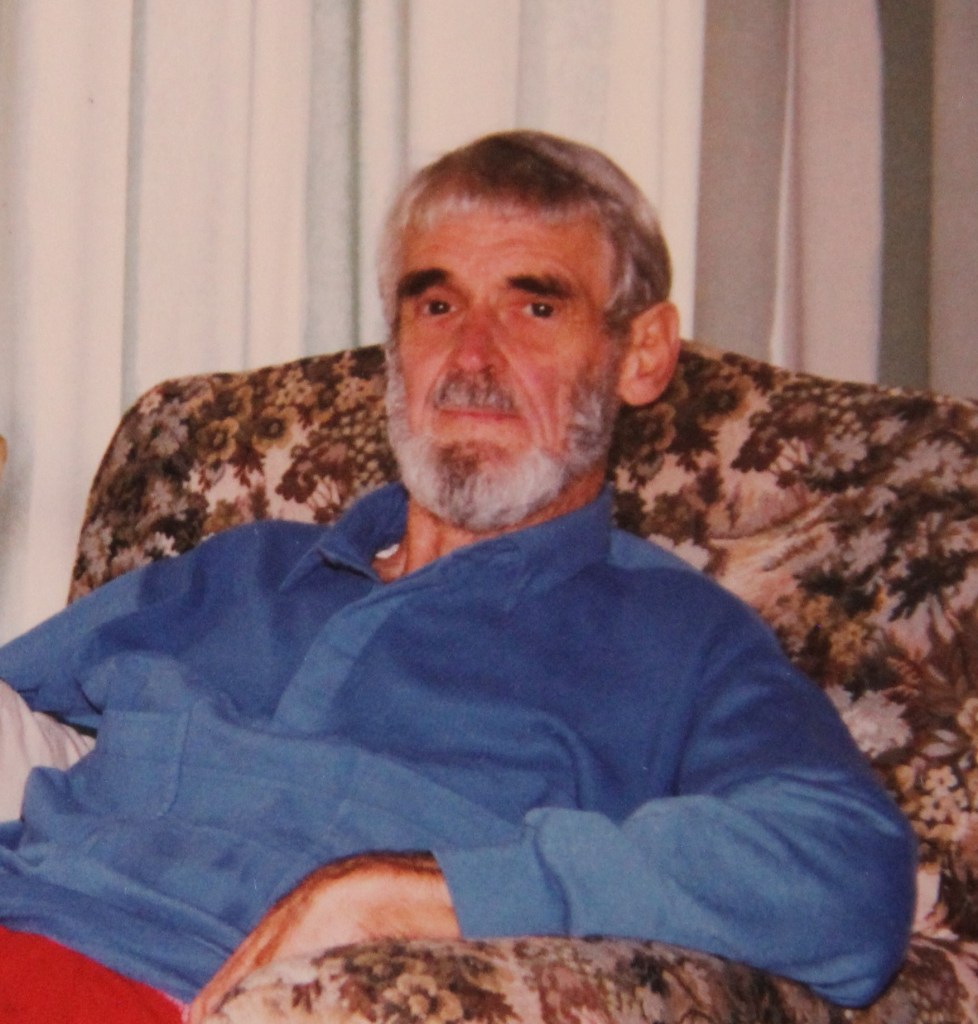

“He was also so well-tuned in walking in other’s moccasins. I recall his first words to me on returning to me in the waiting room after receiving the news of the state of his cancer, “…such a nice young man that”. Referring to the doctor who must have had to dish out similar bad news day after day.“

In those short three months between his pancreatic cancer diagnosis and his death, I spoke to him often about how he felt about his condition and the dire diagnosis. He was remarkably phlegmatic about it, and he accepted his lot with equanimity. He felt he had had a great life and had no burning sense of leaving things undone or unsaid. At the time, I was amazed by how well he managed this. I’m sure, were it me, I would have, in Dillan Thomas’ words, “…raged, raged against the dying of the light.” He had, after all, lived a mere 73 years, and I felt he should have had many more years to share with Mum. As it was, he had less than four months from when they returned from the Bay of Islands in late January 1998. He died at their home on Green Road on the 28th of May, 1998.

Leave a comment