Dad’s father, John Murray (1885-1973) was the first of our branch of the Murray’s to have been born in New Zealand. His father, John McLeod Murray (1856-1943) came to New Zealand from Scotland as a 10-year-old boy in 1866, and his grandfather and great-grandfather (all Johns) came in 1858. Their departure from Scotland and their early days in New Zealand were a complicated story of ambition, regret, drunkenness, and ultimately family success and they very much shaped the course that the family took in New Zealand in subsequent years. So, it is worth relating in some detail.

The Scottish Heritage

We Murrays are a part of the Scottish clan, Murray of Atholl. This clan had its beginnings in the 12th Century in Scotland. At the time, much of Scotland was ruled by a bunch of native Gaelic clan warlords, particularly in the north. They fought among themselves, frequently raided the lowlands to the south for cattle and other produce, and, more significantly, resisted the rule of the Scottish kings. Not unlike the efforts of early colonisers in New Zealand, King David I of Scotland attempted to bring some order to this and to give some protection to the lands in the south. To help him, he imported several Flemish enforcers to suppress these unruly natives.

One of these was a guy by the name of Freskin (d circa 1171). He was a Flemish nobleman and, by all accounts, a very effective warrior. For his services, King David I granted him lands at Strathbrock (in Lanarkshire and West Lothian near Edinburgh) and to the north in what is now the county of Moray in the highlands.

Freskin had one son, William (died c. 1203), who took on the name Moravia – of Moravia, or “of Moray” in English and Murray in the Lowland Scottish language. William’s descendants included Sir William Moray of Bothwell (died c.1278) and it was Sir William who held extensive lands in Lanarkshire, Berwickshire and at Lilleford in Lincolnshire.

They were a politically influential and powerful family that significantly shaped Scotland through the 13th and 14th centuries. William de Moravia’s grandson, Walter Moray of Petty (d.1278), was the Justiciar of Lothian from 1255 to 1257, and his son, Andrew the Elder of Petty (d. 1298), became Justiciar of Scotia, the most senior legal officer in the Kingdom of Scotland. He inherited the title Earl of Bothwell through his wife (she was from the Oliphant family, but her name is unknown). One of his descendants, Walter Murray, began the construction of Bothwell Castle in the mid-13th Century and was hugely wealthy and influential. His castle became one of the most powerful strongholds in Scotland and was the seat of the chiefs of Clan Murray until 1360, when it passed over to Clan Douglas through want of a male heir. At some time in the 14th century, some of Walter’s family moved south-east to settle on his Berwickshire lands. Our branch of the family is likely descended from these settlers.

Despite their ancestors having come to Scotland as enforcers of a rule the natives did not support, the clan was staunchly Scottish from its very early days and often fought for Scottish independence. Sir Andrew Moray the Elder and his son were part of a force attacked by the English King’s (Edward I) army in the Battle of Dunbar in 1296, which marked the end of the First War of Independence. The Scots were defeated, and the English seized much of the Scottish Lowlands. Andrew The Elder was carted off to the Tower of London in chains and died there in 1298. Andrew The Younger, a prisoner of lesser importance, was imprisoned in Chester Castle, but he escaped and proceeded to muster a force in Scotland to rebel against the English. This culminated in the Battle of Stirling Bridge in 1297, where a force led by Andrew Moray the Younger and William Wallace defeated the English. Andrew The Younger died in that battle, but his young son, Sir Andrew Murray (1293-1338), took up the cause of Scottish independence. Five years of age at the time of his father’s death, he had been taken hostage by the English and lived for some years in England. However, he escaped and returned to Scotland to support King David II of Scotland in the Second War of Independence in 1313. He took on the title of Lord of Bothwell previously held by his family and was twice appointed the Guardian of Scotland.

It is not clear exactly when the Murrays of Berwickshire split off from what was to become the clan Murrays of Tullibardine and Atholl; that part of the clan that has its seat at Blair Castle near present-day Perth and who was to attain the chieftainship of the whole clan. However, this likely occurred very early, probably around the 14th century. The Murrays of Tullibardine and Atholl were descended from those who held lands in the highlands in Moray and later Perthshire, while the Berwickshire Murrays descended from those who held land in Lanarkshire and Berwickshire and who moved south-east sometime in the 13th century.

One of the more significant members of the latter branch was John Murray (d. 1640), the 1st Earl of Annandale. He was the Groom of the Bedchamber to James VI of Scotland and was granted the title for his efforts to support the union of the English and Scottish crowns – a delightful piece of irony given his family’s history of fighting the English.

It seems then, that our branch of the Murray Clan were not Highlanders as Dad believed, but Lowlanders. Those who consider themselves the ‘true’ Murrays of Atholl (those that remained in the highlands around Perthshire) considered that the branch that moved to the lowlands in Berwickshire were somewhat lesser beings. Mum relates in her diary of their travels in England and Scotland, that when visiting Blair Castle, they were accorded some respect until it was disclosed that Dad was connected to ‘that lowland lot’.

The Immigrants

Scottish farmers

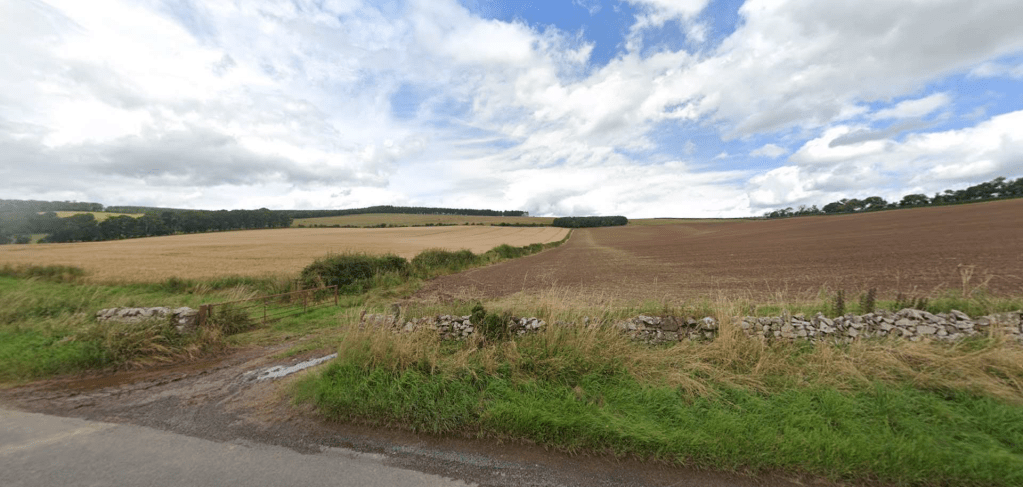

The New Zealand connection begins with John Murray (1786-1863), born in Foulden in Berwickshire in 1786 (he was Dad’s great-great-grandfather). He was the son of a prominent Foulden farmer, George Murray (1743- 1835), and his wife, Isobel (nee Wilson, b. 1789), who were themselves from a long line of Foulden farmers.

In 1815, John married Jane (or Jean as she was known to her family and friends) Hunter (1795-1872). Jean was from nearby Duns, although she was born in Moray in northern Scotland. About the same time, John acquired a lease of 880 acres of land at Marygold in the Parish of Bunkle and Preston, some 10 miles northeast of Foulden (insert footnote re 1851 census). The land was leased from Lord Douglas Gordon-Hallyburton (insert footnote) (a distant relative), and it had probably been in the wider family for many years. Oral family history refers to land farmed by this family at Ladywell. This name does appear on maps of the time, some 6 miles southeast of Marygold. However, there is no record of John Murray owning or leasing land in Bunkle under that name. I suspect, then, that this was the name he gave his farm in Marygold. The name Ladywell occurs in several places around Scotland and is featured in several Murray of Atholl records. So, it may have previously been used for lands held elsewhere by his ancestors, just as Dad had done with their farm at Kaharoa.

Over the next 17 years, they had six children, Margaret (b.1816); Thomas (1817-1899); George (1818-1889); John (1824-1898), Dad’s great-grandfather; James Hunter (1829-1907); and William Archibald (1832-1900). The family farmed sheep with a Border Leister stud and grew ‘corn’ (wheat, barley and oats). Over the next 38 years, they improved the land and established themselves as prominent and respected farmers in the area, employing many people (reference).

John Murray Snr.’s ambitions to improve the land were evident in a letter he wrote to Lord Douglas Gordon-Hallyburton dated 24 December 1841, where he asks somewhat obsequiously for approval and support to undertake some tile drainage on 100 acres of the lease. However, the letter was never sent, and it is unclear whether the drainage ever got done. I had always wondered why it was not sent, but it seems Lord Douglas died the day after the letter was written – on Christmas Day, 1841. Clearly, John felt that it would be pointless to send it.

Dad’s grandfather related a story in 1932 in a brief family history in which he said that Thomas took some Border Leicester rams to the Great Exhibition in Paris in 1854 (it was actually in 1855) and was awarded a bronze medal that he said he had held until it was stolen in a house break-in. The story relates that Napoleon Bonaparte was most impressed with the rams and gave instructions for them to be acquired. Thomas refused to sell them but agreed to gift them to Napoleon instead.

By the mid-1850s, the farm was doing very well, John Snr. and his sons were regarded as innovative and capable farmers, and he was well respected as a prominent member of his community. The five sons were in their early twenties to mid-thirties and were presumably all engaged in farming in one way or another. Son John (1824 – 1898) was a possible exception as he had married a city girl from Edinburgh and may have been living there at the time.

Despite their apparent success, John Snr., Jean, and their five sons (history doesn’t relate to what happened to Margaret) made the decision to emigrate to New Zealand in 1858. We can only speculate as to why they would do this, but it would seem reasonable to assume that it was ambition.

Even with a relatively substantial lease for the time, it would never be sufficient to provide for the ambitions of five sons and their families. New Zealand offered a unique opportunity to acquire land beyond what they could have dreamed of in Scotland. It is also possible that they all possessed that inability to sit still for any length of time, a characteristic which seems to be highly prevalent in the Murray gene pool.

In search of land

So, in 1858, they gave up their lease, said goodbye to their family, and moved to New Zealand. At the time, son John (Dad’s great-grandfather) was married to Mary Hamilton McLeod, and they had a two-year-old son, John McLeod Murray (1856-1943). However, he left these two behind in Scotland. Mary remained and died there in 1865. After his mother’s death, John McLeod Murray came out to New Zealand to join the family and arrived in Dunedin in 1866 as a 10-year-old.

Sons John, James, and William Archibald were the first to arrive aboard the “Nourmahal”, London – Dunedin on 5th May 1858. They began the task of finding land and a home for their parents to settle in when they arrived and land for themselves to farm.

John Snr. Jean, George and his wife Ann, their three children, and Thomas arrived aboard the “Agra”, London – Dunedin on 27th October 1858. John Snr. and Jean were 77 and 63 years old, respectively, at the time of their arrival in New Zealand.

When they first arrived in Port Chalmers in October 1858, John Snr., Jean, Thomas and a young single woman, Jane, moved into a house that their son William had found for them somewhere to the east of Port Chalmers, possibly in present-day Deborah Bay (footnote referring to Jean’s diary). It is unclear where Jane fits into the story, but she came out with the Murrays and was possibly an employee. She features heavily in Jean’s writings at the time, and she appears to be treated like another member of the family. George, his wife Ann and their three children moved initially to a small property at Burnside – the present-day industrial area of Dunedin. I don’t know where John, James, and William, who had been in New Zealand for six months, were living, but they all made regular appearances at their parent’s house in the first six months.

There must have been some land with the house they leased, as this is where they initially kept the livestock that they had bought with them (the sheep proceeded to produce lambs in February). John Snr. and Jean did not venture far from here in those first six months, but they went to Port Chalmers occasionally, once walked to the ‘flats’ (probably around Roseneath) and only once went into Dunedin:

24 January 1858. We have been at Dunedin which is not a more respectable like place than Chirnside (a town in Berwickshire just to the West of Foulden) nearly all the houses are wood. By chance met George and James. The family were at Caversham. Called for Mrs. Murrell and took tea with Mrs. Livingstone. Experienced much kindness from them. Posted a letter to Mrs. Guthrie. (reference Jean’s diary)

The sons, on the other hand, were constantly on the move, mostly by boat and on foot. Thomas bought a horse after a couple of months, but it seemed that they mostly walked everywhere and spent much time exploring Otago.

At some point after that first six months, the family bought a small block of land near Glenore, north of Milton and near what was to become the Glenore Railway Station. Here, Thomas, John, James, and William built a house made of compacted mud and straw for the family. This was to become the homestead for the 8,000-acre Mount Stuart Station, which Thomas later subleased from a John Cargill1 in partnership with a Mr Musgrave. That house is still there today.

After a temporary stay at Burnside, George, Ann and their family moved to East Taieri onto a property they called The Grange, where George substantially enlarged his Border Leicester flock. James and William Archibald purchased 3,000 acres at Waitahuna, north of Mount Stuart, which they called North Branch. By 1868, they were farming these three properties together, sharing the work and regularly moving stock between properties. Sheep grazing was clearly a significant focus, but they were also growing ‘corn’ and, with that, using new reaping and threshing machines that were not widely used in New Zealand at that time.

While these three properties were being farmed as one entity, it seems Mother Jean was managing the finances. His diary shows that she had a keen interest in finances, recording how much things cost and what they received for their produce. She also kept a bank cashbook in which she recorded all bank transactions in meticulous detail and maintained regular balances. This would have represented their working capital and amounted to around £8,200, which, in today’s terms, is around $2.2million. They were, therefore, running a substantial operation.

John Snr. and his wife Jean

We can infer from the things John Snr. did throughout his life something about the person he was. He was clearly a capable and innovative farmer and was very well respected within his community in Berwickshire. He was also ambitious and forward-thinking enough to up-stake his whole family and move to New Zealand, which would have taken some considerable courage at that time, especially when it was driven not by economic desperation but by ambition. Unfortunately, Jean’s diaries don’t shed much more light on his personality. She rarely refers to him; when she does, it is Mr. Murray. She records that he was devout, read much, and liked to walk and investigate this new land they chose. Beyond that, there is nothing. She does not record any opinions or observations that he might have had on what their sons were doing or what he thought of this new land he’d adopted.

John Murray Snr. died at their home at Glenore in 1863 at the age of 77.

Jean lived for another 9 years after her husband’s death. She remained at Glenore, living with Thomas, John, and ‘Little John’, and it seems from her diary that she continued with her keen interest in the family business affairs and continued to worry about her sons. She rarely left the home, but she had a constant stream of visitors to dinner, many of whom stayed the night.

She was probably a typical woman of her time who demurred to her husband’s wishes but who, nonetheless, managed to exert significant influence on what the family did. She was clearly highly intelligent and, through the force of her own will, managed to keep the family together while she was still alive. She brought that deeply entrenched sense of class that existed in the UK at the time. She regarded herself and her family as having a certain elevated social position. Interestingly, in her diary, she refers to fellow landed wives as Mrs. this and Mrs. that, while she refers to fellow shipmates from ‘steerage’ and the workers’ wives simply by their surnames. This is not to say that she demeaned them. In fact, she often really enjoyed their company, and it seems they, too, enjoyed hers, but she was always conscious of the class difference. Having said that, she was not afraid to get in to do the washing, make jam, and clean the house, and she would often enlist the help of her sons in these chores. Perhaps also in keeping with women of her time, she was deeply religious and wrote a great deal about the blessings of God and life lessons from religious thinkers and scholars.

She too, died at Glenore on the 20th of January 1872.

The Five Sons

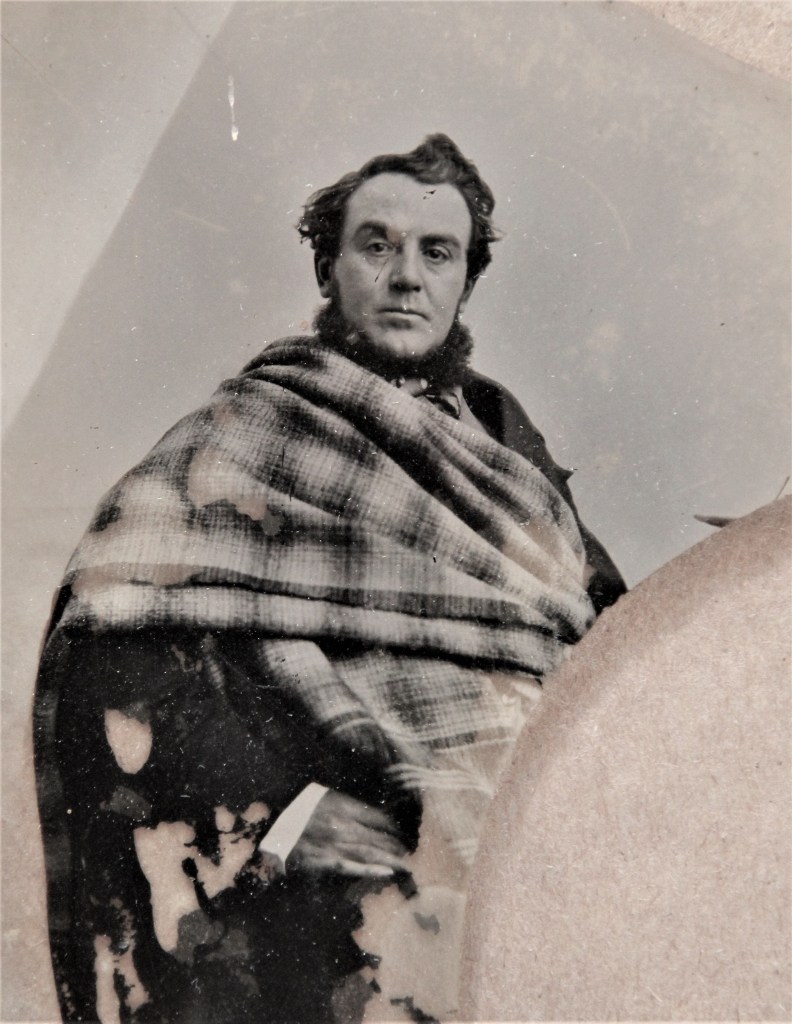

John struggles to settle

John Snr. and Jean Murray’s son John (1824-1898), Dad’s great-grandfather, was the only one of the five sons who did not acquire land when they arrived in New Zealand. He lived at Glenore with his mother and older brother Thomas and worked on the family farming business, but it seemed that he did not have his heart in it. He struggled to settle and became moody, argumentative and a worry to his mother. This was perhaps not surprising given that he possibly regretted abandoning his wife and child in Scotland and maybe also because he wasn’t enamoured with the farming life.

After 10 years in New Zealand, he was still living at Glenore and working on the farm, but he had taken to drink and was increasingly troublesome. There are several telling entries in Jean’s dairy in 1968 that reflect the state of her son John’s mind:

25 January 1868. John, I regret to say, is causing me much grief.

19 March 1868. John ordered to leave the house, but he is still hanging about.

20 March 1868, Thomas and Little John (John McLeod) gone to North Branch with 600 sheep. John again has been away all day and I am alone left to deplore, among other things, the misery he has bought upon himself, but he still has the view, that in persisting with this behaviour, that he is correct.

9 April 1868. McMaster here for sheep. John sent the horse with him, but he has been in that state of mind to abuse all.

16 April. John still under the influence of drink. He has been in bed all day and has not come into the house tonight.

18 May 1868. Rob here for sheep. John still given way to intemperance.

This perhaps goes some way to explain why Little John, as he was called (John McLeod Murray, his son and Dad’s grandfather), was in later life an ardent tea-totaller and partly why he got on so well with his father-in-law, George Devey, who was a staunch Methodist and prohibitionist.

The family stuck with him and largely kept him out of trouble. He went north to Piako in the Waikato with his younger brother, William Archibald, in the mid-1870s and worked with him in developing the Annandale Estate. In his paper on William Archibald Murray, Hart suggests that he may have had a financial interest in that property, along with Thomas. However, he showed more interest in the mining operations in and around Te Aroha and Wairongamai at the time. He was recorded as developing land and doing land deals in these areas in the early 1880s.

He died at his son John McLeod’s home in Waitekauri in 1896 at the age of 72 year.

William Archibald Murray

William Archibald Murray (1834-1900) was probably the most ambitious and self-confident of the brothers and the one whom the other brothers tended to follow. He became a Member of Parliament for the Bruce Electorate in 1871 and retained the seat for 10 years. When he and James sold in Waitahuna in around 1875, he purchased the Maungatapu block, 3,727 acres, in the Piako district near what was to become the township of Morrinsville.

He ultimately acquired around 12,000 acres of both freehold and Māori leasehold land in the Piako district. This he named the Annandale Estate after his 17th-century ancestor, John Murray, the 1st Earl of Annandale. Most of this was sold in 1884, but William Archibald retained some land in the area which he called Mount Pleasant Estate. He remained here until around 1890, when he sold this and, with his brother James, purchased 6,000 acres of largely undeveloped land at what was to become Glen Murray, his portion of which he called Bothwell.

While he was at Piako, he was involved with mining in and around Te Aroha and Wairongamai with his brother John and was a key player in establishing the first frozen meat shipments to Britain in 1888. He was also a strong proponent of tunnelling the rail line under the Kaimai Ranges to Tauranga. In addition to his interest in farming and politics, he was also an inventor. He shared this interest with his brother Thomas, and between them, they applied for several patents for a range of agricultural equipment such as a wire strainer, a potato planting machine and a device for lifting bags onto a dray. While utterly committed to his new country, he was still deeply connected to his native Scotland and proud of his long Scottish heritage. He was also clearly an enlightened and successful farmer, possessing many of the technical skills and knowledge he felt his new country needed. However, he lacked the interpersonal skills to bring others along with him. He was a highly opinionated and confrontational personality who loved to present his opinions on a wide variety of issues irrespective of the audience. There were also some contradictions between his political arguments and his actions. He strongly advocated for community development but was often accused of self-interest, particularly in benefiting his farming interests. He argued forcefully for settling people on the land, yet he was often accused of being a “land shark” himself. He lobbied strongly for Government investment in drainage schemes and the like but was firmly of the view that the Government should, wherever possible, not interfere in people’s lives.

The Otago Daily Times, in 1881, described him in a summary of candidates for the 1881 election as follows:

William Archibald Murray, the member for Bruce, is a tall, active, restless man with an original, daring mind that, in the days of the Caesars or Stuarts, would have certainly brought him to the gallows. He has no reverence for existing institutions, no veneration for the powers that be, no fear of the most daring novelties, and no want of confidence in himself.

Like his older brother Thomas, William Archibald never married and he died in New Market, Auckland on 26 June 1900 at the age of 68.

Thomas Murray

Thomas (1818-1899) also showed considerable drive and effectiveness as a farmer with his efforts to develop Mount Stuart. He seemed always to be looking to improve things, be they roading, land drainage or agricultural equipment. Like his younger brother William Archibald, he was an inventor, but also like his brother, he had strong views about how the world could be improved and was not reluctant to voice them. He often wrote to the Government and the media about the benefits of land drainage, among other things.

He also gained some notoriety for his involvement in the discovery of gold at Gabriel’s Gully. His nephew John McLeod Murray related a story about Thomas having had a chance encounter with Black Pete who had told him of his gold find in what would become Gabriel’s Gully. On this intelligence, Thomas and others from his church, including a Mr. Hardy, fitted out Gabriel Reid and sent him off to investigate the area. Gabriel was working for Mr. Hardy as a shepherd at the time. His findings from this expedition were to spark the beginnings of the Otago gold rush.

Ultimately, he too moved north to Piako, perhaps attracted by the prospects of acquiring and draining land in the Hauraki Plains, and joined his brothers William and John in developing the Annandale Estate.

George and James Murray

George (1816-1889) also eventually moved north from the Taieri, initially to the Opotiki district, where some of his family remain today, and then to Mangapai, south-west of Whangarei, where he died in 1889. He outlived three wives, the last of whom, Elizabeth Harrison, he married at the age of 66 and with whom he had two surviving children.

James (1829-1907) moved north to the Auckland Province after he and William sold in Waitahuna in 1875. The details of what he did immediately following Waitahuna are scant, but he too may have worked with William Archibald, John and Thomas to develop the Piako, Annandale Estate. In 1889, with his brother William Archibald and two sons, he bought 6,000 acres in the Opuatia block, in the lower Waikato, which they called Glen Murray.

Their legacy

For all their energy and obvious ability as farmers, none of this family left behind a substantial estate. In his paper on William Archibald, Philip Hart notes that even William Archibald’s estate was worth little more than £2,000. The others much less. Presumably, he believed that this was then and is, perhaps now, considered the measure of man at his death. While I can’t agree with this, it possibly demonstrates that this family, at least, was not motivated by money alone, a characteristic inherited by some of their descendants. However, while they may not have acquired great wealth, it was clear that they were able to bring together their extraordinary energy, technical farming skills and innovation to make a significant influence on the development of New Zealand’s early agricultural economy.

It occurs to me, though, that the Murray brothers spent much of their lives in New Zealand, clearing the land of native vegetation and draining wetlands. William Archibald, at least, was a strong political advocate for supporting settler land development, including ‘undeveloped’ Māori land that he felt should be acquired by the Government and settled by those who could make better use of it. This was very much in keeping with the prevailing views of the time; however, the irony is not lost on me that many of their opinionated descendants of today are arguing, perhaps with equal conviction, that our native vegetation and wetlands should be restored, and that Māori should be compensated for the loss of their lands and given more sovereignty over their customary interests.

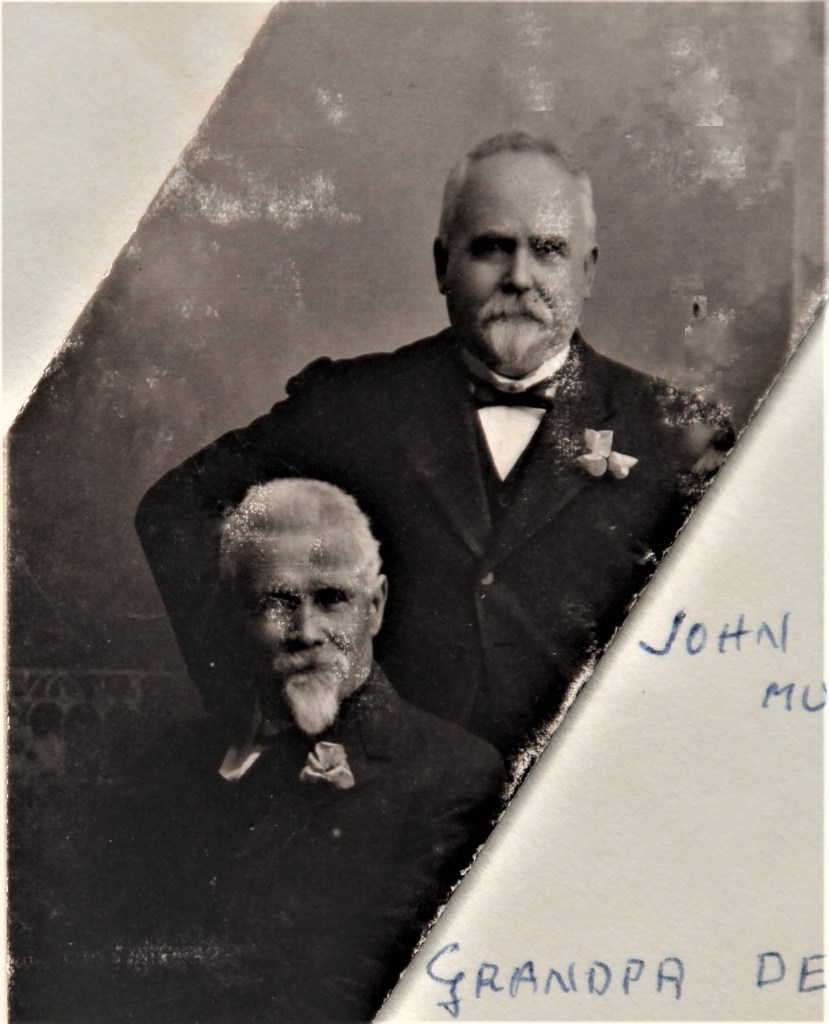

John McLeod Murray

John McLeod Murray (1856-1943), Dad’s grandfather, was born in Edinburgh on 21 June 1856, two years before his father left for New Zealand with his parents and brothers. He eventually joined his father in New Zealand after his mother died in 1865.

He lived with his grandparents, father, and Uncle Thomas at Glenore through his teen years and began working in the family farming business. However, like his father, he didn’t share his grandfather’s and uncles’ passion for farming, so he joined the Bank of New Zealand in Dunedin for a time. He later moved north to Te Aroha, and by 1884, he was working with his father and William Archibald on land and mining deals in the area.

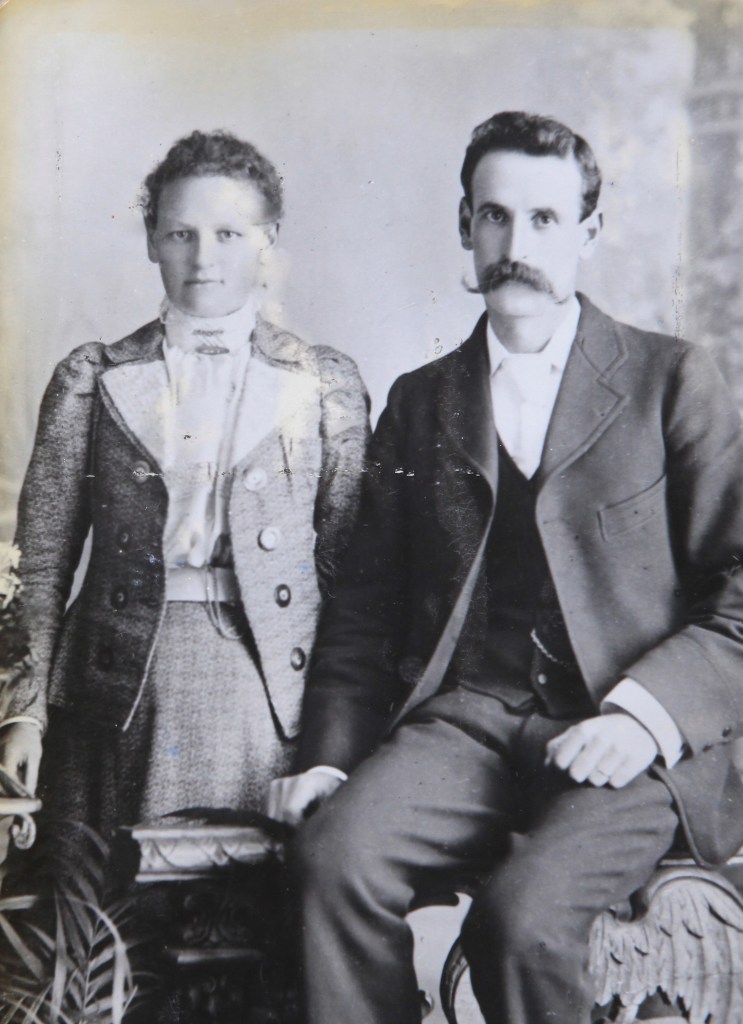

In 1885, he married the daughter of a local Te Aroha identity, Caroline Ida Devey (Kate as she was known), at the age of 27. They had six children; John (1885-1973); George Archibald (b.1887); Eva (b.1888); Laurence Albert (b. 1890); Earnest Robert (b.1896); and Mary (b. 1897 and died as an infant). I don’t recall John’s (my grandfather) siblings being spoken of often when I was a child, although I do recall Aunt Eva, who married George Gardner, and their son Jonny, who was born about the same time as my father.

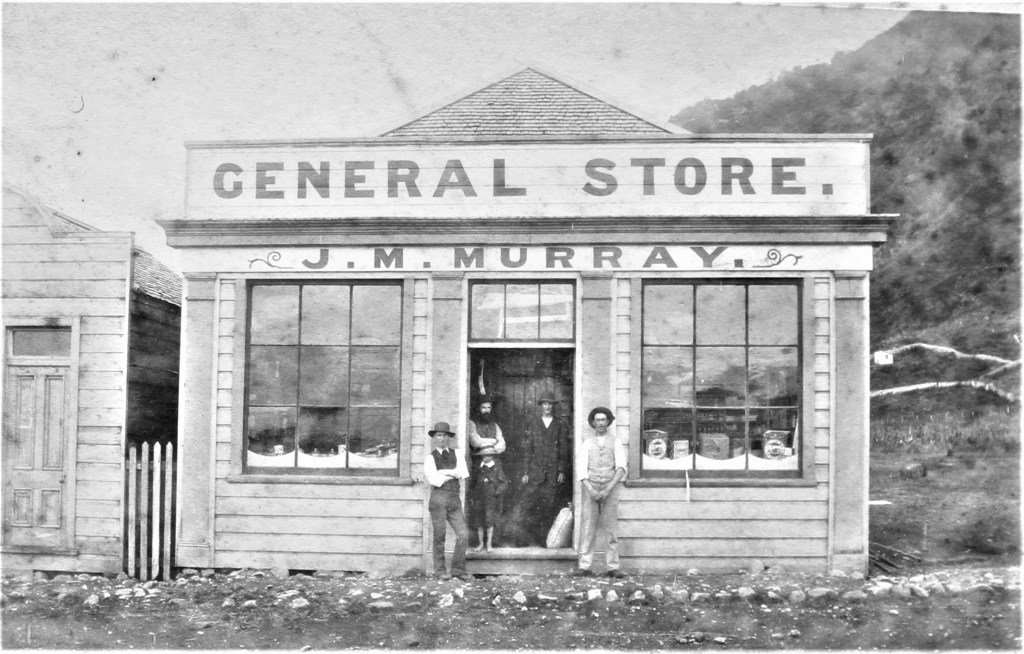

After their marriage, John continued to acquire and sell mining rights around Te Aroha and Wairongamai, and he held shares in several mining companies in the area. While not mining himself, he was involved in opening up mining in the Wairongamai Valley and managed a number of mining contracts. He described himself as a bookkeeper, but also managed and owned stores in Te Aroha and Quartzville where he sold ‘personally selected stock of groceries, drapery, boots and shoes, glassware, ironmongery, and mining requisites, and would deliver goods to Te Aroha’.

In 1891, he and presumably his wife and young family of 3 returned to Lawrence in Otago for some five years where he attempted to find the source of what he thought might be diamonds that Gabriel Reid said he’d found in the ‘Woolshed diggings’ at Mount Stuart and which he’d shown to his father. This was clearly unsuccessful, and in 1895, he returned to Waitekauri and began working for the Waitekauri Gold Mining Company as an ‘accountant, cashier, and storekeeper’.

He remained in that role until 1901. He then moved to Auckland, where he was employed as an accountant for various mining companies. He lived at 1 Kingsland Terrace in Auckland during his later years and ultimately died there in 1943. While John McLeod did not attain the same political profile as his uncle William, he was quite active in local politics and services in the Te Aroha and Waitekauri areas. As a staunch temperance advocate, he was elected to the local licensing authority (much to his Methodist father-in-law’s delight), was on several local committees and was a Justice of the Peace.

Caroline Ida Devey

Dad’s grandmother Kate was born in the United Kingdom on the 11th of December 1865 and came to New Zealand as a young child with her parents, her two siblings and her uncle Jess in 1864. After settling in Thames, from 1883 onwards, they lived in Te Aroha, where her father, George, trained as a cabinet maker, erected houses, built coaches, and was the local undertaker.

George was also a leader of the Methodist community, in particular supervising the Sunday School at Wairongamai for many years. He was heavily involved in the local community and lived long enough to be regarded as one of the ‘old-timers’ of the district and would live until the age of 97.

Caroline Ida’s mother, Ann, first achieved prominence in 1877 for assaulting a teacher because one of her daughters had been chastised. In Te Aroha, she worked as a nurse for many years and was fondly remembered, although previously, when at Thames, her nursing was in part responsible for a maternal death. After she died, the community ensured that her memory was kept alive.

There are no family anecdotes about Kate and I’ve not been able to find anything recorded about her life, other than her role as wife and mother to her six children. She died at Kingsland, Auckland on 29th of September 1934.

Grandpa – John Murray

His early life

My grandfather John was born in Te Aroha on the 1st of February 1885. He spent much of his childhood in and around Waitekauri while his father was working for the Waitekauri Gold Mining Company and in Lawrence while he was searching for diamonds. I can find little written about his early life, but his oral family history suggests that he worked at various clerical jobs in the mining industry around Waitekauri before moving to Auckland in 1903 at the age of 18.

He married Dorothy Pearl Gilfillan in 1911. Dorothy came from a prominent Auckland pioneering family which was deeply involved in the politics and business of Auckland at the time. They had five children: Dorothy Ruth (b. 1911), Pearl Joyce (b.1913), Margaret Blanche – Peggy (1915-1998), John Douglas Gilfillan (1916-1983), and Arthur Keith – Bill (1919-2003). Dorothy filed for divorce in 1923, arguing in the Divorce Courts, as was required at the time, that her husband was “…more attentive to her lady help than to her”. In 1924, she married David James Thorpe.

Oral history (Gwen Murray) recalls that her father retained some responsibility for the care of his young family after the divorce, particularly for Peggy and Bill. So, he wrote to an acquaintance in Waitekauri, Theophilus John Hollis, who had a young daughter, Edith Hollis, whom John had known since childhood and whom he thought might help with the care of the children. Edith was around 22 years old at the time and agreed to go to Auckland to help. They ultimately married in 1925 and, over the next 14 years, had four children: John Hollis (1926-1998), Barbara (1930-1998), Richard McLeod (1934-2001), and Gweneth (b.1939).

Cars and fine furnishings

John (1885-1973) followed in his father’s footsteps in training as an accountant. He worked for Tonson Garlick Ltd., a house furnishing warehouse in Auckland, as their accountant before the First World War and possibly through the war.

He would have been 29 years old when war broke out in Europe, so he would have been eligible for the draft when it was introduced in 1916. However, he never joined the New Zealand Expeditionary Forces, and history doesn’t relate to why this was or what he was doing during this period. However, by 1920, he was working for Hoiland and Gillet Ltd, a car sales company in Auckland as their accountant. It is possible that he had been working for them since 1916.

Following his father’s interest in fine furnishings and equipment, he established a business that imported fine furniture and household goods – probably in the mid to late 30s after the Depression. This did particularly well before the Second World War, and he began to mix with many of Auckland’s wealthy citizens. He built a large house on Selwyn Avenue in Mission Bay, played golf, went on long fishing trips to Great Barrier with his friends, and holidayed in the fashionable locations of the time like Rotorua. However, the Black Budget of 1958 dealt a fatal blow to his importing business with heavy duties imposed on the import of luxury goods. He had to retrench, so he sold the Selwyn Ave house and moved his family back to Exeter Road in Mount Albert to the home they had formerly lived in.

He was the secretary for the Titirangi Golf Club from 1949 and remained in that role until 1965 when he was 80. In 1973, he and Nan sold at Exeter Road and moved into Mum and Dad’s house at Okura after they had left on their first Pacific Cruise. Grandpa died here on the 8th of November 1973 at the age of 88.

A sportsman, a Freemason and a grandfather

Two fixtures of his latter life that spoke to me of ‘Grandpa’ were their house in Exeter Road and his old green 1947 Chevrolet car. The house, with its ‘down the garden path’ toilet, pokey kitchen, and sunless aspect, was classic very early 20th century construction. It was probably quite superior in its day, but by the 1960’s it was very much showing its age. An integral part of this image for me was Grandpa, dressed in a dressing gown and slippers, fly swat in hand, pottering about the house or, more often, the back shed and his workshop. This was always immaculately tidy. Everything had a place and was invariably in its place. Hence, children were rarely permitted entry. The old Chev, the other essential part of my ’Grandpa’ image, must have been a triumph of American engineering at the time as it was always there, and it always went. He had bought it new, retained it right through my childhood and still held it when he died in 1973, despite being forced to give up driving some years before after one too many narrow shaves on the road. It still ran well even then.

Despite my vivid images of him as a grandfather, I never really got to know John the man. While capable of telling a joke and teasing grandchildren, he mostly seemed aloof and uncommunicative. He rarely travelled out of Auckland and seemed to spend much of his time at the Titirangi Golf Club when not at home. As a passionate golfer and someone who always felt the need to belong, the golf club must have been a haven. He had had a long history with the club, was well respected there, and was made a life member in 1967 (an honour bestowed on very few). It was little wonder, then, that he was reluctant to retire and would retreat to the club often.

Another significant interest he had was Freemasonry, an interest he presumably inherited from his Grandfather John (he was appointed “Vice Grand” of the Otago branch of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows in 1876. ) As he was not a religious man and was not particularly politically motivated, it seems the secular and apolitical nature of Freemasonry appealed. It was a group with whom he felt a real sense of belonging. As is the practice of Freemasons, he never spoke of it, but papers he left behind suggested that he was an active member throughout his adult life and attained some senior positions as a Lodge Master in New Zealand and an Expert Master in the international field.

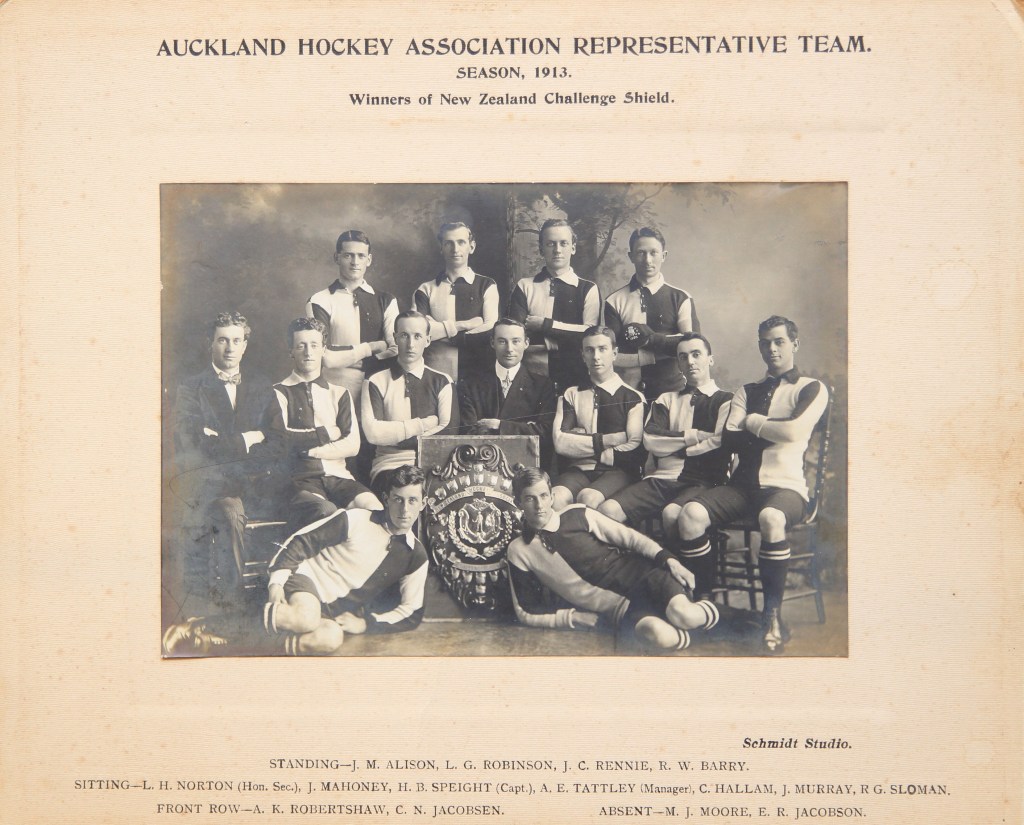

Golf was not his only sporting interest or skill. In his youth, he was apparently an excellent hockey player and cricketer. Several media commentaries sang his praises as both a batsman and a bowler. There is a letter written by a senior manager in the Waitekauri Mining Company in 1903, as he moved to Auckland, to a senior partner in an Auckland law firm recommending John Murray as “…an excellent field and a promising bowler” for their cricket team.

He played hockey from the time he moved to Auckland in 1903, at least through to 1913, when he played for Auckland and they won the New Zealand Challenge Shield. He was also a keen tennis player and according to his son Richard, was a very good one. So, clearly, he was both an adept sportsman and a keen sports follower.

Another interest and skill he had as a younger man was photography. This, too, he inherited from his father, who was apparently a keen photographer. Sadly, few of their photographs survive. I recall several boxes of glass plates that Grandpa left behind. I spent many hours browsing through these and feeling at the time that he had a great eye for a photo. Many of these were of holidays in Rotorua, Onetangi, Tindell’s Beach and fishing trips to Great Barrier, but many too were of landscapes, which suggests that he had more of a feel for the land than I had given him credit for.

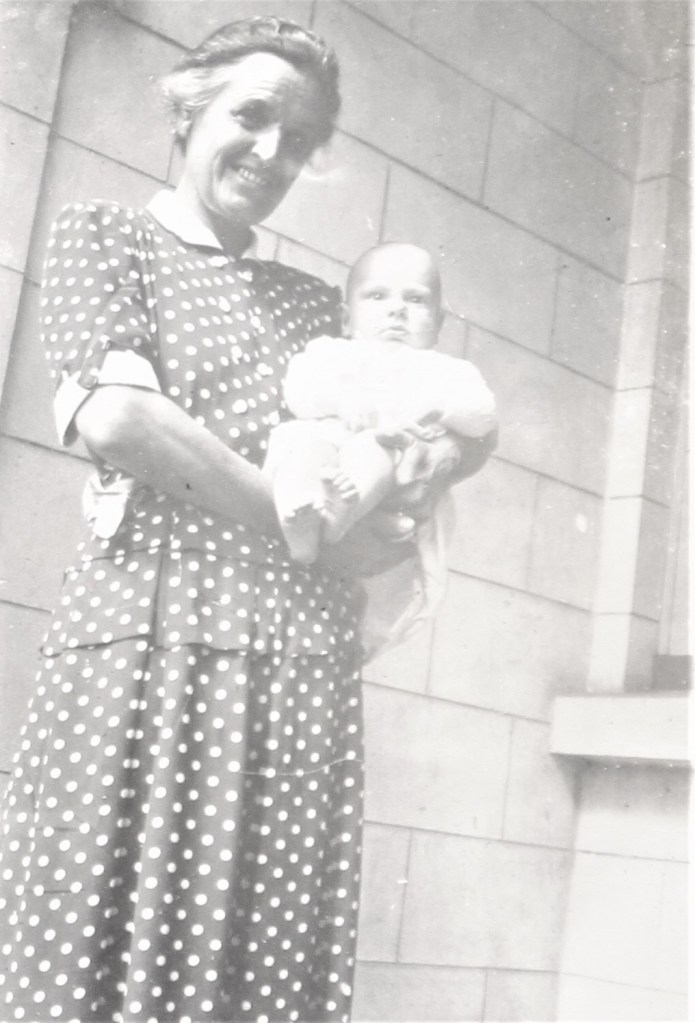

Nan – Edith Murray (nee Hollis)

My grandmother, Edith was one of four daughters born to Theophilus John and Edith Emily Hollis (nee Corbett 1870-1948) in Waitekauri; Mary (1901); Edith (1902); Kathleen Jean (1909-died as a child); and Joan Marion (1912).

Nan’s mother’s parents, Edward Mann Corbett (1842-1898) and Edith Corbett, nee Mainer (circa 1842-1872), were very early settlers in the Thames and Waihi district, having arrived in New Zealand from Berkshire with their young son Edward in 1864. Edward Mann Corbett was an engineer who became a key figure in opening up and managing mining operations, initially around Thames and later at Waitekauri. Nan’s mother, Edith Emily, Edward and Edith’s third child, was born in a nikau whare at Waitekauri and was reputed to have been the first person of European descent to be born there. Nan’s grandmother died of consumption while Edith Emily was still a young child, and Edward Mann Corbett then married Emily’s sister, Mary Anne Mainer, with whom he went on to have ten more children. Their homestead at Waitekauri, known as ‘Shirley’, is still there today and has recently been restored.

Mum recorded that Edith Emily was a very capable and intelligent woman who was responsible for building the very strong bonds that existed within their family. She did not meet her until she was in her late 70s, just before she died, but Mum said she was struck even then by her sharp mind and worldly outlook. Her granddaughter, Gwen, remembers her as a very stern and even grumpy old woman.

One of Edith Emily’s sisters-in-law, Bessie Corbett, was apparently an intrepid and beautiful lady, and she was said to have shot pheasants out of her living room window in Mission Bay, Auckland. Once, on holiday at Hooker Lodge, word went out that breakfast would be late because no one had come to milk the cow. Bessie responded, “Get me a bucket; I’ll milk your cow!”

Another story that Gwen relates involves the local postman. Bessie was apparently lining up a peahen with her rifle out the bedroom window. As the postman knocked on the door, she whipped the gun around in fright and shot a hole in the bed. The postman was convinced that she’d shot someone and fled. She spent the rest of the day carefully sewing up all the layers of the mattress so her husband John wouldn’t discover what she’d done (he was a teacher).

Nan’s father, Theophilus John Hollis (1866-1943), was also from a Coromandel mining family. His father, William Hollis (1828-1897), was born in Kent, England, and his mother, Agnes Hollis, née Graham, was born in Midlothian, Scotland. They had both emigrated to New Zealand with their respective families in the late 1840s and met and married in Auckland circa 1850. They later settled in Te Aroha and became involved in the mining industry. Theophilus John was born in Te Aroha, and he and his wife, Edith Emily, remained in or around the Coromandel mining towns of Te Aroha, Waitekauri and Waihi, working in the mining industry until the 1930s. They then moved to Takutai Avenue Bucklands Beach, overlooking what is now the Half Moon Bay Marina, where they remained until their deaths. Gwen and my mother remember him as a quiet and unassuming man for whom family was an important part of his life.

Nan was exceptionally close to her sisters. Gwen recalls her being constantly on the phone with Mary and often with Joan and her aunt Kathleen (from Mauku). They frequently holidayed together at Onetangi on Waiheke, Lake Rotoiti and Tindell’s Beach on the Whangaparaoa Peninsula and often took their parents with them.

Mary married Harold Taylor (1898-1977) in 1921, a successful baker who owned and ran Taylor’s Bakery on the North Shore. He was later to become a significant influence in shaping my father’s love for the sea. I remember him to be a kind, gentle and clever man, while Mary always seemed to be complaining – mostly about Harold, who she frequently called a fool. She probably loved him dearly, but as a child, I was horrified by this and could never understand why he never reacted. They had two daughters, Jocelyn and June, who Dad was very close to and with whom he spent much time as a child.

Joan was, I felt, an absolute delight. I remember her as a bright, inquisitive person with something interesting to say. She married Ian Stewart sometime in the early 1950s, and they lived most of their married lives in Gisborne, where Ian was a bank manager for the Bank of New Zealand. They had one child, Ann, with whom my dad was quite enamoured. She was very clever and charming, always doing interesting things, and I suspect she shared many of his interests. She married George Richardson, a farmer from Kawakawa Bay in East Auckland, and they remain there today.

Another member of the wider family who both Nan and Dad were close to was Kathleen Hill nee Corbett (1890-1975). She was Edith Emily’s half-sister and Nan’s aunt, being one of the younger members of Edward Mann and Mary Ann Corbett’s large family. She married Arthur Vincent Hill (1898-1975), who, with his brother, owned a large swathe of land between Pukekohe and Waiuku in the Mauku area. Kathleen was the energy in the partnership, according to Gwen, and she, too, had a big influence in shaping Dad’s interest in farming. They had no children of their own but brought up Allan Farley (a relative of Arthur’s) from the age of nine, who later married Dad’s sister, Barbara. They were also frequent hosts to Dad and his siblings during holidays.

My memory of my grandmother Edith (Nan) was of a warm and loving person who took real delight in having her grandchildren around her. She never seemed to growl and was very inclined to spoil us. There were lots of good memories of trips to the Farmers and the Auckland Zoo on the tram for us ‘country bumkins’, and there were several memorable holidays at Tindell’s beach where she and Grandpa had a section next to the Taylor’s bach. Family for her was a complete preoccupation – she didn’t seem to have any other interests, and I don’t recall her having much of a friends network beyond her sisters. Her life, then, must have been very confined. Sadly, though, I never really got to know her as a person, so I never understood whether this was an issue for her. She and Grandpa were highly dependent on each other in their later lives, so she did seem to struggle after he died. She was to live another twelve years after his death and died on 25 March 1985.

Footnotes

- John Cargill was an early settler in Otago and held large sheep runs in Otago and Southland, including one at Mount Stuart. It was this property that Thomas Murray and Mr. Musgrave sub-let. Cargill was later elected to New Zealand’s 1st Parliament in 1853 and was the Bruce Electorate representative before William Archibald Murray’s election to this seat.

Leave a comment