I have struggled with describing my mother. Conventional wisdom suggests that at some stage in your later youth, you cease seeing your parents as mum and dad and get to know them as people. This holds for me to only some extent. When I joined them on their first Pacific cruise at the age of nineteen, I got to know her and Dad better as their own people, but mostly she was simply Mum – and I loved her dearly to the day she died.

Her early life

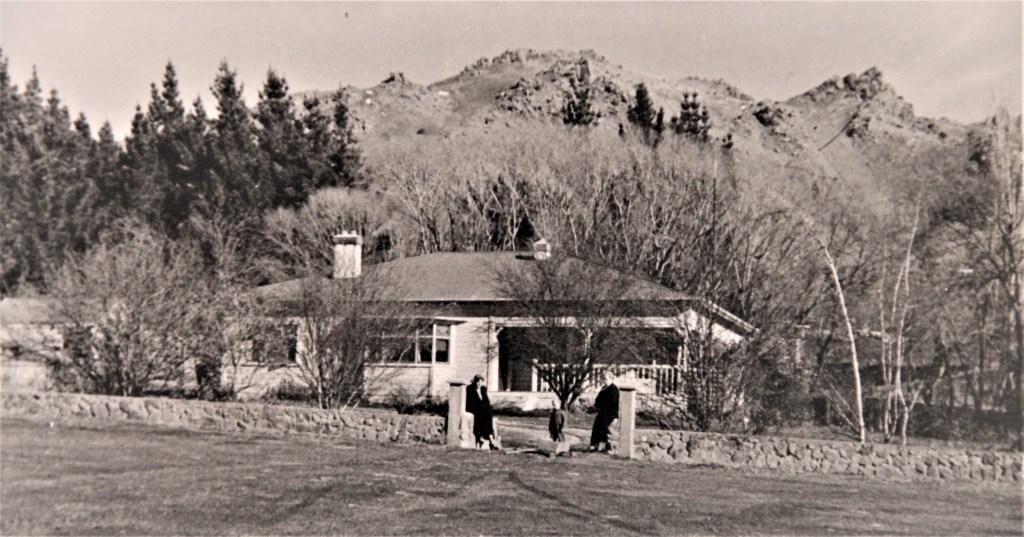

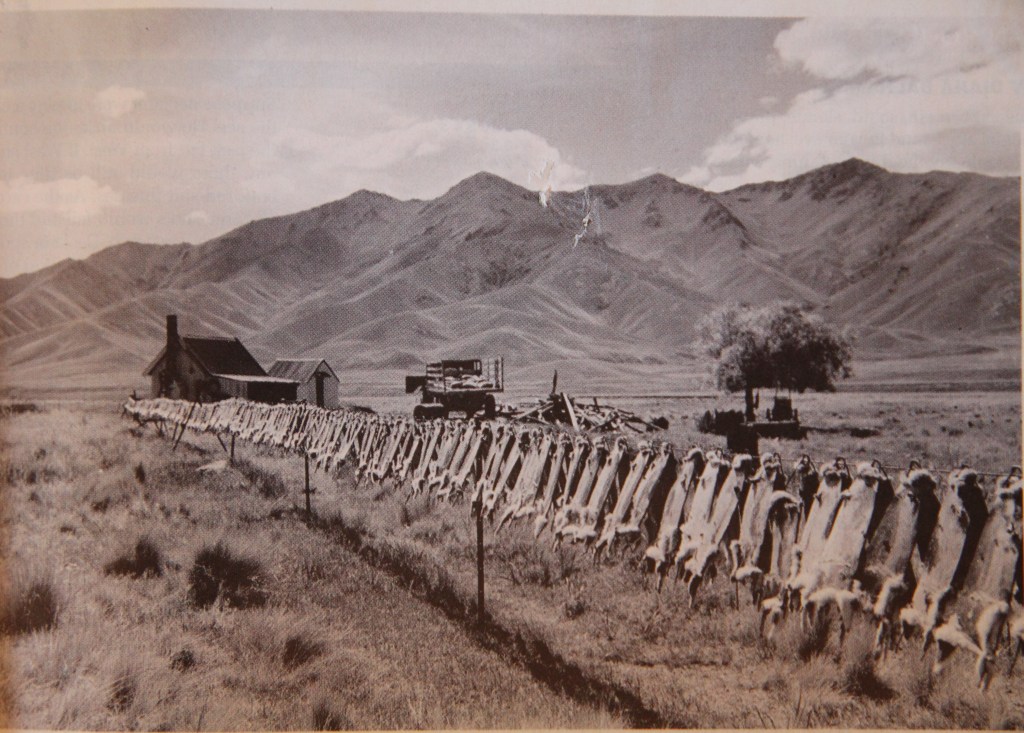

She was born to a South Island high-country farming family in 1930. This was more an accidental farming family than one deeply entrenched in farming over generations, but a farming family they were, nonetheless. Her father was trained as a blacksmith and passionate about everything mechanical, including cars and motorbikes. Her mother was the ultimate city girl who grew up in the Hutt Valley.

Her father had fought in the First World War and had come home physically and probably psychologically damaged. When he returned, he took a job selling tractors in Dunedin. However, he was also successful in getting a services settlement block in the Maniatoto, which they were required to live on, so they ultimately moved onto the farm. Mum’s father continued to sell tractors during the week, leaving her mother at home on her own during the week with two young daughters. Worse was to come (see the piece on Dorothy Jones below).

This then, was the environment within which my mother was born on the 7th of April 1930.

It is perhaps a testament to the strength of the human spirit that her parents were able to give Mum what she described as an idyllic childhood (she wrote in her notebook entitled ‘Message to My Grandchildren’:

“If, as I’ve heard it said, that happy childhoods are not remembered, then mine was idyllic.”

She did remember it though, and she had many stories to tell about it, only some of which are recorded in the abovementioned notebook.

She recalled that she once went to visit an old family friend and neighbour, Syd Andrews, in the Chalet Maniatoto Hospital. He was going on 100 years of age, but he gave her a lecture, which she felt was well rehearsed, about being grateful that she was allowed to run wild and not be protected like her sisters had been. She was indeed grateful. She understood that the farm and the outdoors were not her mother’s thing, so she was thankful that her mother was supportive of her involvement in these things as a child. She wrote that it brought to mind a chook bringing up a duckling, not really understanding the mechanics but loving it, nonetheless.

As a young child, she contracted polio, and while it was not severe enough to warrant her being confined for weeks in those huge iron lungs of the time, she did have to wear callipers on her legs for some years. However, she said she could never recall this inhibiting her significantly.

Of Maniatoto, she wrote:

“…it was a pretty restrictive society and short on drama, but for an only child with a taste for freedom and the outdoors, it was perfect. Two boys on the station next door my own age and a series of old men who worked on Clachanburn were my companions”.

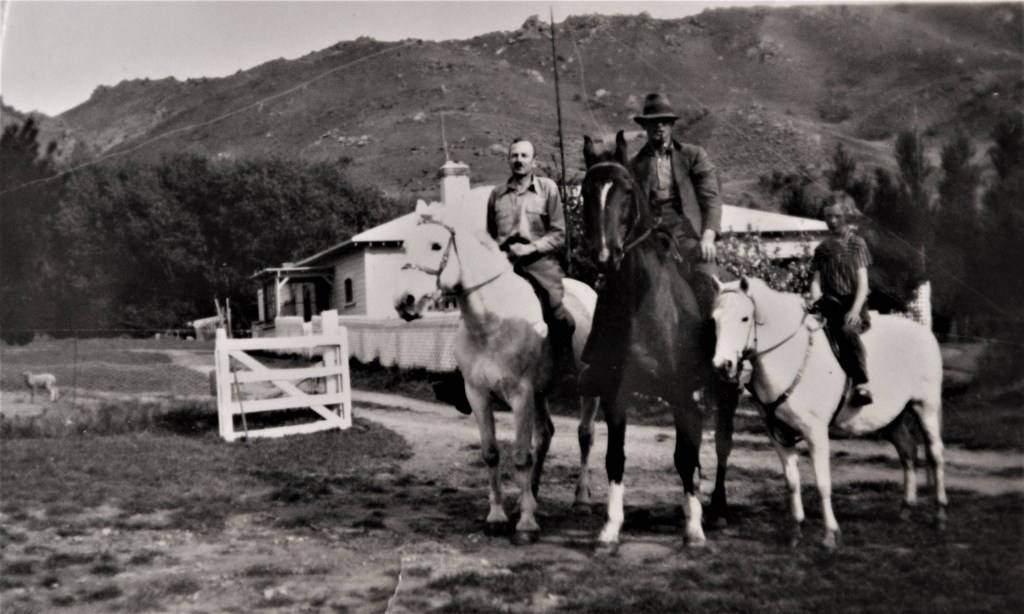

The two boys she refers to were Dixon and Rodger Andrews whose parents farmed the property next door. They became her proxy brothers, and almost every story she told of her childhood at Clachanburn involved these two boys. (It was their father, Sid, who, years later, reminded her that she should be grateful for the freedom she had).

Another proxy brother she had was Laurie Falconer, a young man who Grandpa Aitchison had employed before the Second World War. He was some years older than Mum, but they got on very well. Mum said it occurred to her only years later how tolerant he was of her always tagging along with him on the farm when she was a small child. Laurie would become a close friend of the Aitchison family and would later be a great help as Grandpa Aitchison’s health deteriorated. I have explored this in some more detail under Grandpa Aitchison’s section.

One of the old men she refers to and who is often featured in her stories is Mr. Peek. He was reputed to have run away from home to become a postilion boy on the carriages travelling between the gold fields and Dunedin. He worked for Grandpa Aitchison as a rabbiter and general hand. Mum claimed that the smell of some soups would always instantly take her back to his hut where, through the winter, he’d keep a soup pot hanging over his fire. He never cleaned it but periodically, he’d top it up with leftover meat, vege-trimmings and water.

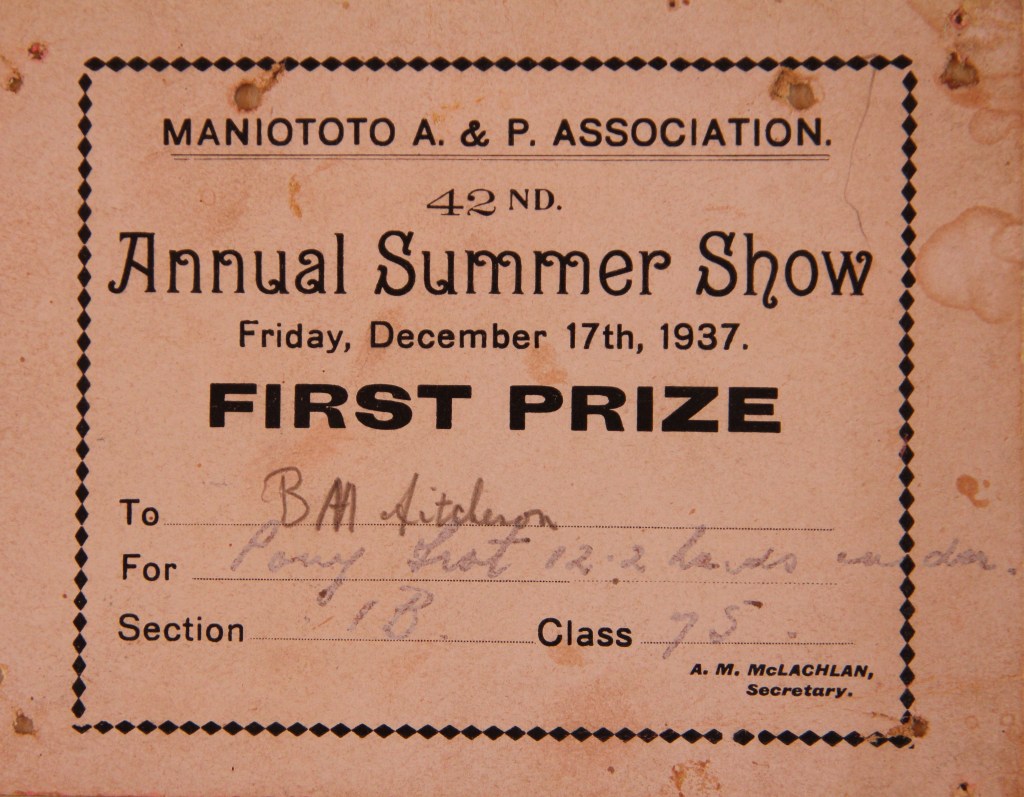

Rabbits featured heavily in her childhood memories. On those dry, grazed landscapes, rabbits thrived, often reached plague proportions, and came close to driving people off their land across Otago. Rabbit control was, then, a matter of economic survival. She recalled that you could go outside on an evening, clap your hands, and then watch the whole hill move with rabbits. She also recalled rabbit drives where they would seal the rabbit warrens in a rabbit-fenced paddock and drive thousands into netting and scrim enclosures. She was well schooled in a wide range of gruesome ways to kill a rabbit, and applied these regularly, not just because it was needed, but also, it seems, because it was fun. Her favourite pets at the time were two greyhounds and some ferrets that they used to hunt down rabbits. She bought her first car at 16 with the proceeds from selling rabbit pelts.

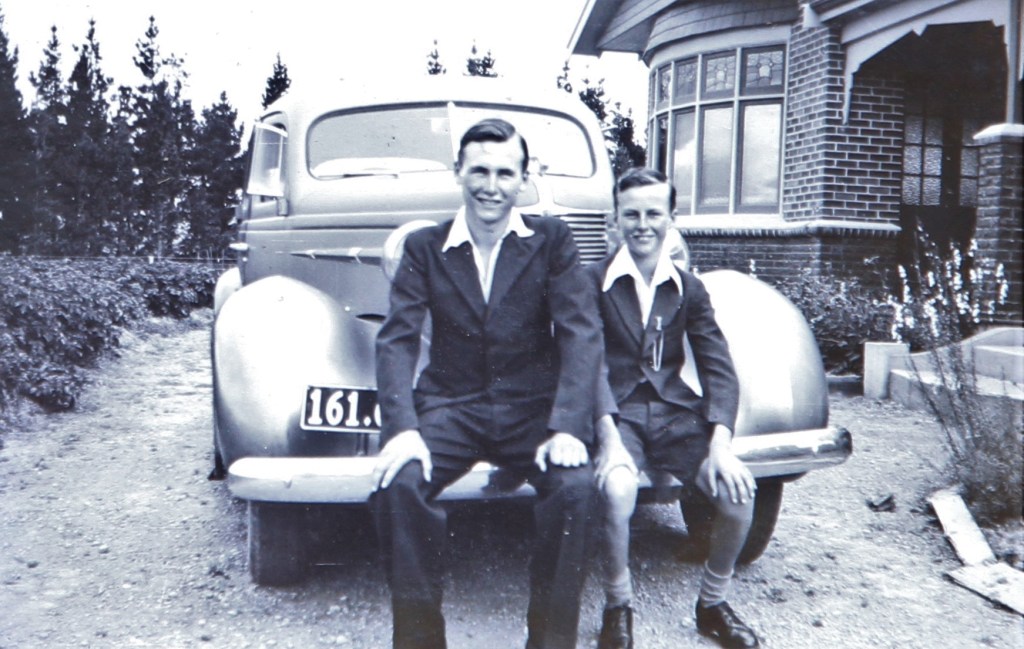

While her first car came at 16, she got her driver’s license at 12. They were making hay at the time and being helped by the local Ranfurly cop. He noticed Mum driving the truck on the road and said; “That girl needs a driver’s license”. The next time he visited, he bought one out for her.

Primary school was eight and a half miles to the east at Patearoa. She was quite an enthusiastic student and quickly developed a passion for reading. She also enjoyed the added social contact this gave her. She would claim to be very happy in her own company and would not actively seek social contact, and she admitted to being socially lazy. It was true that she needed her own space from time to time, and she could sometimes be reluctant to initiate social contact, but when she found herself in others’ company, she enjoyed it and excelled in building social connections.

Widening horizons

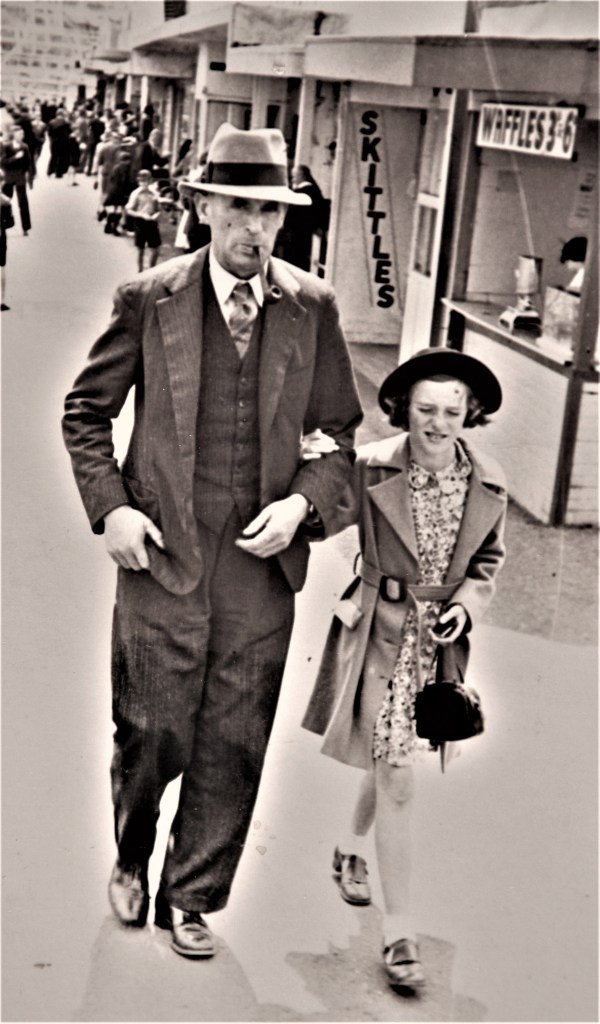

Life as a child was not all confined to the Maniatoto. She and her parents seemed to travel to Dunedin often, especially after the Depression when things began to lift financially. They also frequently travelled to Wellington to visit her mother’s and father’s families. She recalled feeling like a rough country kid in the urban context with her many cousins, aunts and uncles, but it seemed she had no difficulty adapting to this environment. It also gave her a taste of what life could be like beyond the Maniatoto.

However, the real shift in opening up her horizons came when she went to boarding school in Dunedin. The nearest high school was 18 miles away in Ranfurly, and although there was probably a school bus, her parents decided to send her off to Columba College. This probably reflected her parents’ belief that Columba would not only give her a better education but would also expose her to better influencers.

She was at Columba for three years, from 1943 to 1945. Again, she was a capable student whose school reports showed promising results but also included frequent teacher observations that she could do better. She was curious and enjoyed English, history and geography and here, she cemented her love for reading. Science and maths were not strong points for her, although to be fair, they were not emphasised much by the school for young ladies who were expected to become housewives, or if they must work, nurses or teachers. I recall her grumbling about this when Kay was trying to decide what career training she should do. She also enjoyed the social aspects of school life and met several people at Columba who were to become lifelong friends.

She reluctantly left Columba in 1946 to return home to help run the farm as Grandpa Aitchison’s health deteriorated. She often felt that this had stunted her academic development, and she occasionally said that she regretted never having the opportunity to undertake some more formal academic training. She certainly had the intellect and the curiosity for it. But her father’s failing health and the norms of the time didn’t make room for it when she was a young woman, and in later years, family and other commitments conspired to get in the way. However, she didn’t let that stop her from delving into a wide range of subjects through her reading. She was, as a result, very well informed and could speak knowledgeably on all manner of subjects, but usually to do with social history.

She would not have described herself as a natural athlete and she was not at all competitive, but she did enjoy sports, particularly hockey. She played for Columba College and later for Otago. After she left school, she continued playing for the local Patearoa team and for Otago. In 1947, Otago won the “K” Cup, a national trophy. Mum claimed she was mainly on the bench, but she clearly enjoyed it.

Romancing and spreading her wings

While she never said as much, she resented being tied to the farm after returning from Columba in 1946. She had been exposed to wider possibilities beyond the Rock and Pillar Range and wanted more. Her diary of 1946 refers to several barneys with her parents that usually ended in tears (hers). It was unclear what these were about, but it seems likely a tussle between what she would like to have done and what she was required to do. None of this stopped her from getting out and around the district, though – going to dances almost every Saturday night and staying out until the wee small hours of the morning.

Several young men in the district were vying for her attention, and one or two would-be mothers-in-law were keen for her to meet their sons. Her boyfriend at the time was a young man by the name of Tom Aitken whose parents farmed further up the valley at Paerau. However, her diaries record that she finally brought that to an end in early 1946:

February 23rd “…Tom rang from Mitchell’s – in at tennis – I didn’t know what to say”

March 1st “I wrote the long-planned letter of finality to Tom. Planned it in bed last night. NO SLEEP, but I’m glad it is over.”

Many years later, after Dad had died, she re-connected with Tom. They spent many happy times together after that, mostly travelling about New Zealand and Australia on Charolais tours – Tom still lived on the farm at Paerau and bred Charolais cattle.

Also, in early 1946, she met a young man working for their friend and neighbour, Laurie Falconer. His name was Jack Murray, and he features regularly in her diary writings through that year; hesitantly at first, but with more enthusiasm as the year progressed. They met often at dances and eventually travelled to various social events together. On one occasion, she writes:

“Driving along the Puketoi Run Road recently (circa 2001) on one of my rare visits to the Maniatoto, I changed down to go up a small incline. Suddenly, I was plunged back more than 50 years. Returning from a dance at Gimmerburn, JH was driving my mother’s newish Standard (affectionately referred to as the Matchbox), Dickson and Rodger and someone else in the back seat, all of us singing and light-hearted. Our driver forgot that the road curved to go down the slope and we bumped over the road’s edge, flatted the fence and stopped halfway down the hill. No problems: we pushed mightily – back on the road and home again. Come morning, JH faced my father and explained our misdeed. They examined the car, and miraculously, there was no damage. “Just go back and fix the fence before anyone notices”, he said. This we did and those standards are still there, with a small kink in them, and the pigtail joins in the wire are still visible. Nothing much changes there….!”

She admits in her diary to being a little shattered when he went back north toward the end of 1946 to work on Hauturu at Kawhia and then on to Waihau Downs in South Canterbury. Still, he managed to find his way back to the Maniatoto on a regular basis over the next three years. She, too, found her way to Auckland and Tindell’s Beach in 1946/47 to meet his family. In December 1949, they were married.

I am guessing here, but I feel that as a nineteen-year-old who, through her reading, her wider family connections, the years at school in Dunedin, and travels to Wellington and elsewhere, she was aware of the potential for a life beyond the Maniatoto. She was too curious to let this possibility go, too keen to experience other places and people, and too determined not to follow many of her peers into marriage with a local farmer and living a life as a farmer’s wife. While she loved the Maniatoto dearly and treasured it as a childhood home, she needed to get away.

So, here we have this young woman, keen to break free from the ties of home and the Maniatoto and begin a new life of her own making.

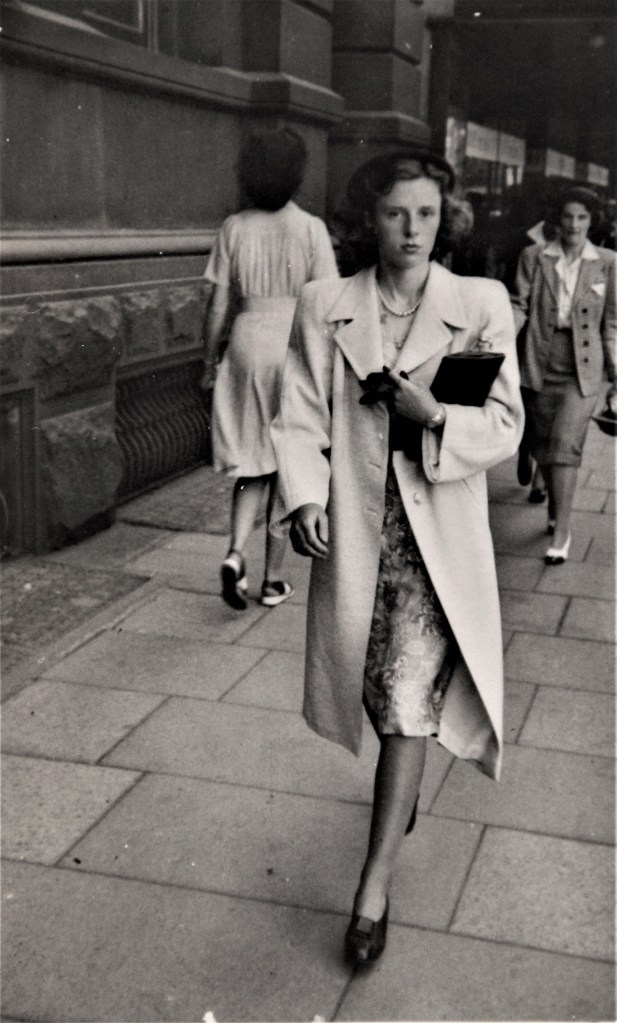

A woman with presence

My mother had a certain presence about her that many who met her responded to warmly. It was not that she was full of self-confidence or had a forceful personality. It was just that she was very self-possessed – mostly calm and in control and was completely comfortable with who she was. She was socially adept and could read people well. She often claimed she had many weaknesses and shortcomings, but she had reconciled these. She was quite content with the package that she felt she was as a person. She was not competitive or even ambitious in the conventional sense, so she never measured herself against anyone else’s yardstick.

She did, though, have a very deep-seated sense of her own and her family’s social position in life. This was not expressed by her saying or even feeling that she was better than others, but she held strongly to a set of behavioural codes and standards, and to obligations that came with her position in life. These codes were not unlike the ethic of a country gentleman or gentlewoman and had their roots in 19th-century British society. In her view, some people will hold to these codes, and some will not, but she and her family would most certainly do so. She believed she got this from her grandmother on her father’s side, Alice Aitchison (nee Sanders), who was apparently a formidable woman with a keen sense of her and her family’s social position.

While Mum would deny it, she was a people person – she found them endlessly fascinating. She would often say she was perfectly happy to wait on some event, provided there were people about that she could watch. She was not so gregarious as to want to always engage with people, but when she did, she would want to know what made them tick and hear their stories. This, of course, always endeared her to those she met.

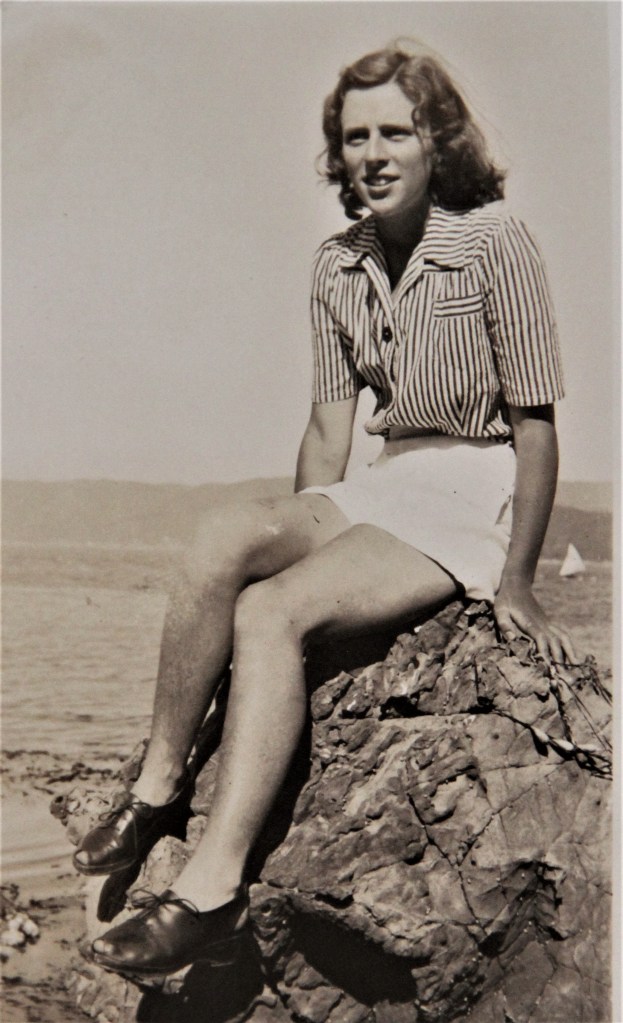

The experiential person

She was always more curious about people and places and things real than she was about abstract ideas. She wanted to understand how things and people were the way they were and to understand their historical context, but she rarely had regrets or thoughts about what might have been. She was quite happy to deal with the world as it presented itself to her and didn’t often imagine a world that was different and maybe better. She was also more a sensing person than a reflective one – feeling pride in her family, meeting interesting people or having new experiences, a beautiful flower, a fine horse, a lovely landscape, or the feel of the sun on her skin. These were the things she treasured. Ironically, she was not a ‘touchy-feely’ person – she rarely hugged people and generally avoided direct physical contact with most people.

On the subject of sun, she recalled, as a child, lying on a still-warm rock in the late afternoon sun on the hill behind the Clachanburn homestead. She watched the shadows creep across the plain before her as the sun went down behind Rough Ridge, and she recalls feeling a resentment at the half-hour less of the sun the homestead got as it was tucked under the eastern side of the hills. She recalled always feeling the same resentment whenever she was stuck on the shady side of a hill. There was, of course, no such thing as sunscreen in her younger days, but even when it did arrive, she eschewed it and made little effort to cover up in the sun. Thankfully, she would generally turn nut-brown in summer rather than burn.

A poem she wrote in 2004 captures this attraction to the solid and real and to good experiences.

Let us search for the verities,

The things that are solid and real.

Children, our friends, trees and sunsets.

The human contact which warms the heart,

And the understanding which needs no words.

The crisp air of early morning,

And the beautiful symmetry of alpine plants.

Snowclad mountains,

And that glorious green of nurtured pasture.

B. M. Murray 2004

Another love she had was walking, not just for the physical activity it provided but also for the sensory pleasures it gave her. She would notice the colour of the water in the estuary, see a new flower in a neighbour’s garden, and notice the new supply of driftwood brought down by the last storm and get great pleasure from gathering it up and taking it home for her fire. When walking past a herd of jersey heifers, she would remind herself again, “…how much nicer they look than those motley crossbred things you see around today.” She might equally, in her mind, tell the owner of some lambs she passed that they needed a drench.

Dad was not a keen walker, but she found opportunities to do this even when he was alive. Mostly short walks that would accommodate Dad, but after he died, she set out on a whole range of multi-day walks on her own and with family and friends. In her later years at Greens Road, the local walking group trips became an important part of her social calendar and connected her to many new and old friends. In her last days at Summerset Falls Village in Warkworth, walks were one of her greatest pleasures.

Her love of walking sometimes mixed with her sense of adventure. Pip recalls walking with her high in the Sierra Nevada in 1974. They were trying to cross a steep snow slope (without an ice axe or crampons) when they realised they couldn’t go on – it was too steep. Pip froze; she burst into laughter. I had a similar experience with her as a boy when we were trying to climb steep coastal cliffs in the Bay of Islands.

Her life was, then, a series of adventures and experiences. She had little patience for sitting still. This was partly driven by her ethic of hard work and making an effort, but it was also driven by a firm belief that we should be out gathering experiences. Life came and went willy-nilly, and we should make the best of it while we could. There were a number of quotes that she’d posted into their scrapbooks that captured this belief in the ephemeral nature of life, the desire to resist the tyranny of old age, and the need to make the best of our lives while we could:

From the Ruba'iyat of Imar Khayyam

Into this universe and why not knowing,

Nor whence like water, willy-nilly flowing;

And out of it, as wind along the Waste,

I know not whither, willy-nilly blowing.

Edward FitzGerald’s translation

Do not go gentle into that good night - exerpt.

Do not go gentle

Into that good night.

Old age should burn and

Rage into the close of day.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Dylan Thomas

First Fig

My candle burns at both ends;

It will not last the night;

But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends—

It gives a lovely light!

Edna St. Vincent Millay

Dost thou love life?

Then do not squander time,

For that’s the stuff that life is made of.

Benjamin Franklin

Bub Bridger’s Blatant Resistance, which Alice recited so well at Mum’s funeral, was another poem on this theme that she loved. I’ve not included the text here, but it can be found on the link here.

The only time I can recall her getting really angry with me was when Pip and I were sitting around home at Algies Bay during a primary school holiday, and I complained that I was bored. She let loose a tirade about the incredible opportunities around us and finished by saying; “do not dare to complain to me about being bored again!!” I never did.

In keeping with her pursuit of experiences, Mum had no ambition for achieving material wealth. Like Dad, she was more motivated by the opportunity to try new things, see new places and experience different ways of living life. One exception to this was her secret love of cars – a love she clearly had inherited from her father. In the late 1950s at Kaharoa, they drove an old Vauxhall Velox, a very functional vehicle that served the purpose but not much more. She had her eyes set on a new Ford Falcon. To repurchase one, you had to purchase Australian currency, and there was a limit to how much you could buy at any one time. So, she set about acquiring the necessary currency over the next year. Sadly, for her, it never happened. Other priorities must have gotten in the way. It was little wonder then that she was appalled when Dad came home with the Simca some years later in Warkworth.

In defense of justice and fairness

My mother had a very clear view of what was right and proper, what was fair and reasonable and what was unjust and unreasonable. She was very tolerant of those whose values were different from hers, and she didn’t rail against injustice or bemoan her lot in life – she could accept with equanimity, the things she had no control over, but she would not hesitate to point out injustice when she came across it.

Her response to the Springbok Tour in 1982 was a good example. She felt that through her reading and having been to South Africa in 1974, albeit briefly, she was reasonably well informed about the apartheid regime there. She firmly believed it was unjust and that New Zealand playing rugby with South Africa gave the regime some legitimacy. So, she quietly took herself off to Auckland on several occasions to protest because she felt her presence there might make a difference. She recalled sitting among several hundred protesters at the Karangahape Road and Symonds Street intersection. Standing behind her on the fringes of the group was Mike Minogue, the leader of the Police Red Squad, giving instructions on his radio to stooges planted in the crowd, to cause a disturbance. This was presumably so the Police could break up the protest. However, a protest organiser beside her also heard the radio instructions, so he warned the crowd not to respond. Peace prevailed, and the protesters remained there all day.

I also saw this sense of injustice in her reaction to my involvement in removing protesters from Bastion Point in 1977. I had been drafted in as part of my work to go in after the Police had removed the protesters to demolish the buildings. She was rarely judgmental, but I was left with no doubt that she did not approve.

She would also react if she felt ‘officious little bureaucrats (in whatever form) with an inflated sense of their own power and importance’ would try to overplay their hand. She would put on her haughty tone and quietly but firmly put them in their place. There were several occasions where I witnessed this, generally directed at men who underestimated the unassuming woman who stood before them.

A mother and a wife

Family, of course, were hugely important, particularly in the latter part of her life. She followed our progress with great interest and took enormous pride in the academic, sporting, career and other achievements of all her children and mokopuna. To some extent, in her last few years, she depended on us all to keep her engaged and interested in the world. She wrote in 1998 – somewhat presciently because, at the time, she didn’t depend on us so much. She was still too busy living her own life:

For my granddaughters. (And I’m sure this also applied to her grandsons.)

Dear ones, will you hear me if I call for you in the night?

It’s your youth I need to warm my aging heart,

Your enthusiasm to fuel my flagging dreams.

Beverly Murray 1998

Kay sometimes said that she felt Mum was too keen to get us out of the nest so she could get on with living her own life. It is true, we did move away from home at a relatively early age. John went off to Whangarei at seventeen, Kay to Massey about the same age, and Pip and I went off south to farming jobs, also around the age of seventeen. I think though, that it was our parents’ desire for us to get on and live our own lives that motivated them, rather than the other way around. Pip remembers seeing her in tears once when, at Waiti, we were all about to go back to our respective lives. In what was meant to be a private conversation with Dad, she said how she so loved having us all there and how she hated to see us go, but she was doing her best to hide it so she wouldn’t appear clingy.

For my part, I felt deeply loved by both my parents. Like Dad, Mum was proud of our achievements but did not try to direct me. She was never judgmental (with the exception of the Bastion Point incident), and she always had a supporting word. Like Dad, I feel sure she loved her children deeply, but like him, she would never have used that word.

We don’t have the advantage of a first-hand view of what Mum was like as a wife and a life companion – Dad’s musings didn’t extend to this. However, I think it is reasonable to say that Dad was exceedingly fortunate to have had Mum by his side through those forty-nine years. He was likely not the easiest person to live with – capable of sharp shifts in mood and temperament, often incommunicative and very often intransigent when he’d made up his mind. She understood him implicitly and trusted him completely. She was also exceedingly comfortable with herself as a person, so she had the strength of character to weather the inevitable storms of marriage. She was almost always willing to follow his lead. That did not mean that she would not encourage him along the way. They would never have gone to sea twice or have travelled to the extent that they did, had it not been for her encouragement. There is no doubt that she loved her husband dearly and missed him hugely when he died, and she was emphatic that she would not have wanted any other life.

She was to have another twenty-four years on her own after Dad died, years she characteristically crammed full with activity and adventures, but more on this later.

Leave a comment