Their provenance

Mum’s maiden name was Aitchison, and through her father’s line, she was descended from the Aitchisons, who lived in the lowlands of Scotland from the late fourteenth century. Family folk law had it that the highland Murrays used to come down out of the hills in Scotland and raid the lowland Aitchisons’ cattle. It’s possible, in fact quite likely, that the unruly highland arm of the Murray’s did just that, but then they probably also raided the lowland Murray’s cattle as well.

The first reference to the name shows up in Berwickshire around 1387. A Johannes Filius Ade (sounding suspiciously like another Dutchman) appears in records as John Atkynsoun. The spelling of the name varied greatly over the next five hundred years, but by the 19th century, it was primarily standardised to Aitchison, and those with the name are considered to be a branch of Clan Gordon. The name appears consistently in census documents in the southern Scottish counties, particularly Berwickshire, Lanarkshire and Edinburghshire, so it seems likely that our particular Aitchisons were descended from this Scottish family.

I have been able to reliably trace the Aitchison paternal line back to a George Aitchison (b. 1760), born in Dunbar, North Berwick some 30miles to the east of Edinburgh) and his wife Jean, nee Irven (b. 1766). They had three children, the second of whom was Charles, born on the 4th of December 1790. At the time, his parents lived in Penicuik, Midlothian, a village on the banks of the North Esk River, some 11 miles south of Edinburgh.

Paper making and the remittance man

Family folk law had it that the Aitchisons owned a paper mill on the Leith, a small river rising in the hills to the south of Edinburgh and emptying into the Firth of Forth through the city of Edinburgh. It was said that this mill produced the paper on which the Bank of England’s paper notes of the time were printed and that Archibald (Charles and Margaret’s third child) was packed off to Australia as a remittance man for fear that he would give away the secret to the watermark used in the paper “while in his cups” – in other words, while pissed.

When Mum and Dad were in the UK in 1989, Mum tried to verify this story in the library at Shap near the Lakes District, where she’d heard that there was a river Leith. An archivist confirmed that no river Leith was nearby, although paper mills had operated in the district for many years. However, none were owned by an Aitchison. She later wrote to the Bank of England to see if they had any record of this mill. They were not able to find any reference to an Aitchison-owned paper mill supplying them with paper, so Mum concluded, somewhat reluctantly I think, that the story had no substance. It was a mystery that would trouble her right up to her death.

Papermaking was a significant industry in the south of Scotland through the 19th century, and in the period when Charles (b. 1790) and Margaret (b. circa 1792) were living in Penicuik, there were six paper mills operating along the North Esk River. Also at the time, Scottish banks were able to print their own paper notes, and many did, given the shortage of gold and silver in Scotland.

She didn’t know at the time (or had forgotten) that Charles (b.1790) made a deposition about his career in 1866. This was documented and later published, and a photocopy was pasted into one of their scrapbooks (footnote – Scrapbook 6.0 Session Paper 595, P 196 ‘Deposition of Charles Aitchison’). He described himself as having been bred a paper maker and said that he had served an apprenticeship for eight years from 1797 (as a seven-year-old) at the Melville Mill in Penicuik. He married a local Penicuik girl, Margaret Murphey (b. circa 1792), and they had eight children, the third of whom was Archibald, who was born in Penicuik on 25 October 1826.

Charles’ (b.1790) deposition suggests that he didn’t own a mill but worked at a paper mill in Colinton on the Leith called Kates Mill. This was owned by Alexander Cowen, who also owned a nearby mill called the Bank Mill, which made paper for banknotes. While they may not have supplied the Bank of England, they would most certainly have provided the Bank of Scotland with their paper, and it is quite probable that Charles and his son Archibald worked at this mill and were privy to the secret of the watermark.

It also seems entirely plausible that Archibald was packed off to Australia to protect this secret, as that is where he went in 1851. However, it may have been that he went at the behest of his employer, Alexander Cowen, to look after his business interests there, as Cowen & Son had significant business interests in Australia through the second half of the 19th century. Archibald was also accompanied on his trip to Australia by his younger brother James, which may support the idea that they went on behalf of their employer.

Paper flower making in France

Another story relating to Charles and his wife Margaret is that their family owned a paper flower-making business in France. Mum recalls being told that her Grandmother Alice Aitchison (1867-1949) went to Europe before Mum was born “to settle Aitchison family business affairs”. She later learned from her mother that she had gone to France to collect Samuel’s share of a paper flower-making business after it had been sold. I have not found any documentary evidence of this, but again, it seems plausible given the family history in paper making. It is unlikely that it was Charles’ (b.1790) business, but it may well have been developed by one of his children. Getting to the bottom of this story has defeated me, but it is perhaps fertile ground for future family historians to explore. As to why Alice went to France and not Samuel; this is another story, but Mum said that simply, she did not trust him to do the job.

Aussie gold

Archibald (Mum’s great-grandfather) and James arrived in Port Phillip Bay, Victoria, in December 1851 as “unassisted passengers” on the ship Calphurnia (reference). They were both single men, Samuel, age 25 and James, aged 17. Archibald spent the next four years or so in Melbourne and met Margaret Henderson, who he married on 24 April 1853. Margaret was born in Coleraine, Ireland, in 1831. She came to Melbourne on her own as an 18-year-old, on an assisted passage aboard the ‘Elizabeth’, arriving in July 1949. Apart from that, I have no other information on her past or why she left Ireland.

They began their married life in Sandhurst to the east of Melbourne and their first child Charles was born there in 1854.

Some months before Archibald and James arrived in Port Phillip Bay, Mrs Kennedy and Mrs Farrell discovered alluvial gold nuggets in Bendigo Creek while washing clothes, and it was this that was to unleash the great Bendigo Gold Rush. It seems likely that Archibald, Margaret and their young son went north sometime in 1854 to the Bendigo diggings. Their second child, Sarah, was born here (in 1855), as were Mum’s grandfather Samuel (1857) and his brother James (1861). While Archibald may well have been trained as a paper maker, he must have also trained as a blacksmith, as his occupation is listed as this from his time in Australia. It is unclear whether he was directly engaged in gold mining in Bendigo or practising his blacksmith trade, but the latter seems more likely, given his listed occupation. By the beginning of the 1860s, alluvial gold was running out at Bendigo, and presumably, demand for blacksmithing work was waning. So, perhaps sparked by news of gold discoveries in Otago some two years earlier, the family crossed the Tasman aboard the ‘Lawrence Brown’ in October 1863. But it was not the gold they were after. It was the business that gold mining would provide a capable blacksmith.

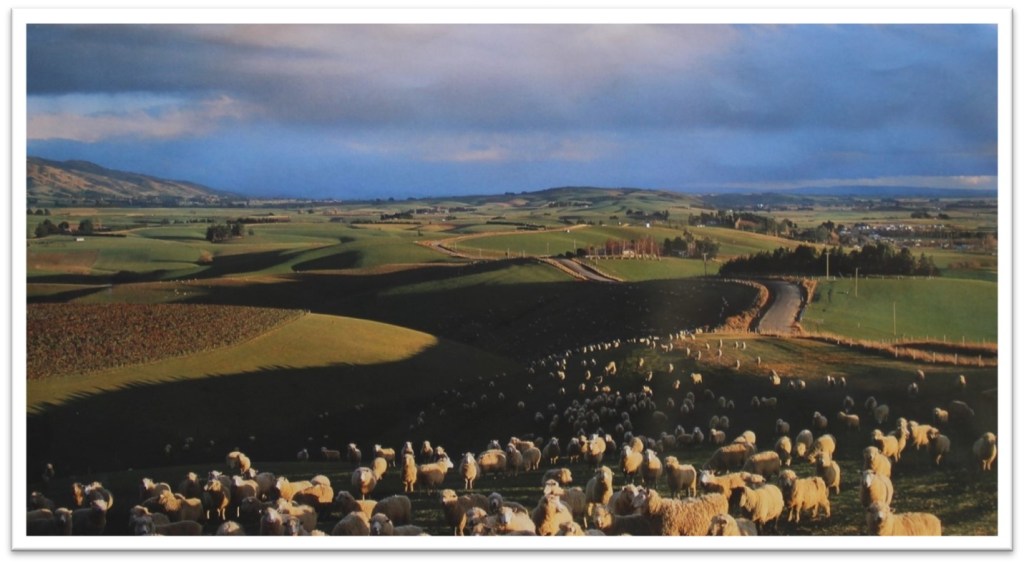

The move to New Zealand

Mum records in her “Message to My Grandchildren” that the family bought land in the north of Dunedin and that this ‘…didn’t immediately develop as desirable real estate’. So, they soon moved west, initially to Tuapeka and then down to Otokia near the mouth of the Taiari, where they remained for 10 years. He established a smithy here next to the hotel, and this became a favourite gathering place for locals on rainy days. He would regale them with great stories of the gold in ‘Old Bendigo’ in Victoria and often provide lodgings for passersby. In the mid-1870s, they purchased a block of rolling tussock country at Crookston to the east of Heriot, which they called Springbank. This was bought under a deferred payment arrangement with the Government. Here, Archibald set up another smithy and became a farmer. As the boys grew, they, too, took up the tools and learned the trade, working alongside their father. This was a particularly profitable time for the family, and as their prospects grew, so did their family. Over the next 17 years, the family grew to 13 children. Perhaps Archibald overcame his tendency to drunkenness if indeed he had one. He may also, like his son Samuel, have found a strong and capable wife who helped him and his family to prosper. Whatever the case, they did very well in this new colony of New Zealand.

Farming and disinheritance

Unfortunately, Archibald and Margaret’s prosperity did not encourage good succession planning. Archibald wrote his will in 1896, leaving his entire estate to his son Robert (who presumably remained on the farm), subject to a life interest for his wife. It seems that none of this was discussed with the rest of the family, so when he died in 1908 (some 10 years after his wife Margaret and 12 years after writing his will), there was some consternation among the family. When the Public Trustee sought probate for the estate, Samuel and his brother William, on behalf of other family members, took out a caveat arguing that their mother Margaret and brother Robert exerted undue influence on Archibald. Before the case came to a hearing, Samuel and William withdrew their claim, but both Robert and the Public Trustee sought costs from them to recover what they’d incurred in preparing their defence. The case went to the Supreme Court in Dunedin in 1909/10, and the judge found in the Public Trustee’s favour, although not in Roberts. The court record does not reveal what costs were awarded.

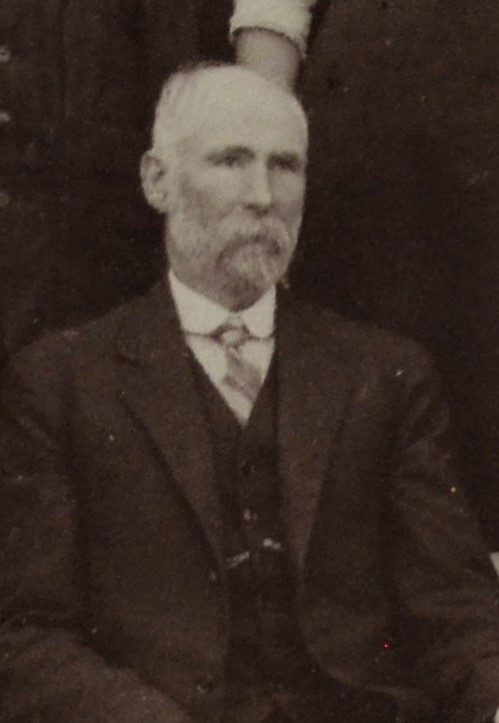

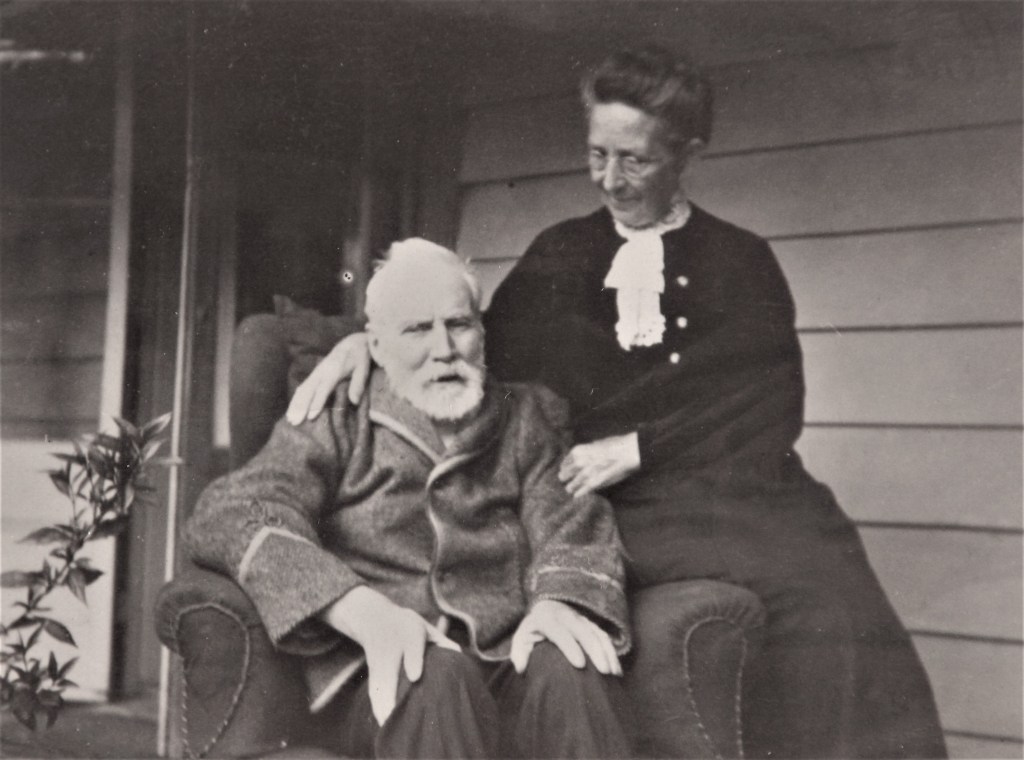

Samuel (1857-1927), Mum’s grandfather, was born in Bendigo during the heat of the Bendigo gold rush and was a boy of six when he and his family moved to Otago. He grew up in an increasingly crowded household, and no doubt, he spent time out in his father’s smithy, helping and learning the trade.

He began his career as a blacksmith, working with his father and perhaps some of his brothers in servicing the blacksmithing needs of the Otago gold miners.

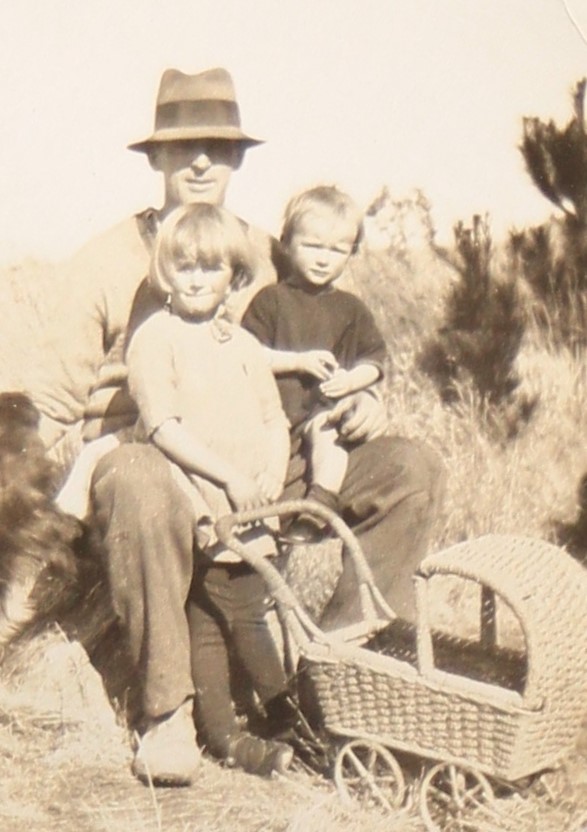

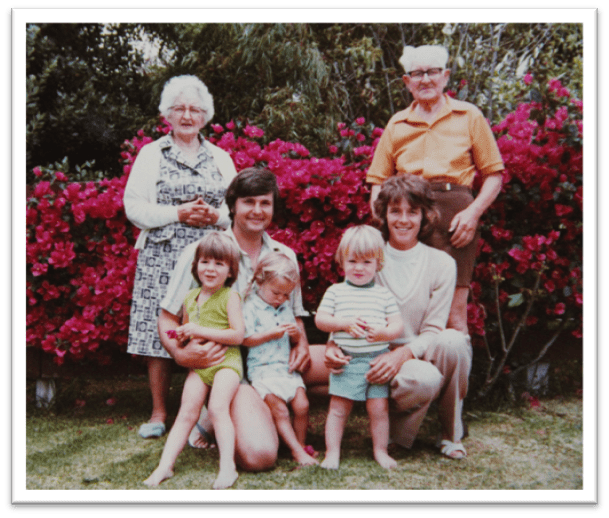

Mum recalls that he was an amiable, red-bearded man with a love for the land and great skills as a blacksmith. He married Alice Sanders (1867-1947) in 1886. At the time of his marriage, he was living on the farm at Crookston near Heriot and was, presumably, both helping out on the land and practising his blacksmithing trade. Public records of the time variously describe his profession as farmer and blacksmith. Their first child, Mabel Elsie, was born in 1888, followed by Vera Ethel (1889), Evelynn Rose (1890), and Charles John (1892) – Mum’s father. There continued to be a succession of children born over the next nine years, the names of whom can be found in the caption of the family photo below. There were seventeen of them in all, and all survived beyond childhood.

The move to Featherston

Soon after their last child, Douglas, was born in 1911, the whole family, or at least the parents and those still living at home, moved to Featherston in the Wairarapa. History doesn’t recall why they made this move, but it can reasonably be assumed that Samuel, having been left no interest in the Crookston farm, chose to set out on his own and resume his blacksmithing trade. Mum records that he prospered here, too, as a blacksmith and encouraged his son Charles into the trade. He still, though, hankered for a farming life. Each year, he would go off to look for a farm to buy. Hunterville was his favourite hunting ground, and I can only guess that he must sometimes have found the land he wanted to buy, but presumably, Alice would not cooperate as he never bought a farm.

We know very little about Mum’s grandmother, Alice before she met Samuel. She was born in Wellington in 1867 and died there in 1949, and I have no record of who her parents were. There is a reference to another family member in Mum’s ‘Letter to Our Grandchildren.’ She says that Samuel’s brother married her sister Edie. There is a record in New Zealand’s register of marriages of Rose Ann Sanders marrying William Aitchison in 1899, who may well be the sister and brother. Beyond that, there is nothing.

Mum notes in her ‘Letter to Our Grandchildren’ that:

“ …. she was certainly a lady of tremendous strength of mind and character who espouses that view of inherent superiority and [the] necessary social commitment [and obligation that comes with this] …, so to influence [her offspring] in later life”.

She was clearly an indomitable woman who, it seems, set the standards for the family and took responsibility for key family decisions. She must also have been quite canny with their money, as it was Alice who held the purse strings. It was also Alice who set off to France to settle Samuel’s paper flower company inheritance, and when she died in 1949, to her family’s surprise, they discovered she owned five houses in Wellington.

Charles John Aitchison

I have always felt that I had known my grandfather well, which is quite untrue as I never met him, let alone got to know him, but my childhood was rich in stories about him. Mum was very close to him and, I suspect, very like him.

His early years

Grandpa Aitchison, as he was referred to in our family, was born in Heriot on the 8th of March 1892 when his parents were living on their farm at Crookston. They had had three daughters at the time, so Charles was their first son. We know little about the specifics of their life at the time, but having been born into what was to become a very large and busy family, he probably spent time out on the farm and learned the basics of farming from an early age. He probably also found his way to his father’s blacksmith shop as his father had done. He was to become the only one of Samuel’s seventeen children to follow him into the blacksmith trade.

Charlie Todd was an early mentor and friend who significantly influenced the direction in which Charles took his life. Charlie was 11 years older than Grandpa Aitchison, but they shared an interest in machines, particularly the relatively new motorcar and the motorbike. This became a lifelong passion for my grandfather and for Charlie Todd, and it would propel Charlie into the New Zealand motor industry as the founder of one of the country’s most significant and enduring car sales companies, Todd Motors.

Charlie Todd came from a background similar to that of Grandpa Aitchison. His parents, like Grandpa Aitchison’s, had been part of the mining boom in Bendigo and had emigrated to Otago when the gold began to run out there. They, too, settled in Heriot, although the Todds were more directly involved in the mining industry, wool scouring and the fellmongery (sheepskins) business. Mum notes that Grandpa Aitchison worked for Charlie in a bicycle shop in Featherston, but it is likely that this was in Heriot before the family moved to Featherston and when he was still in his late teens.

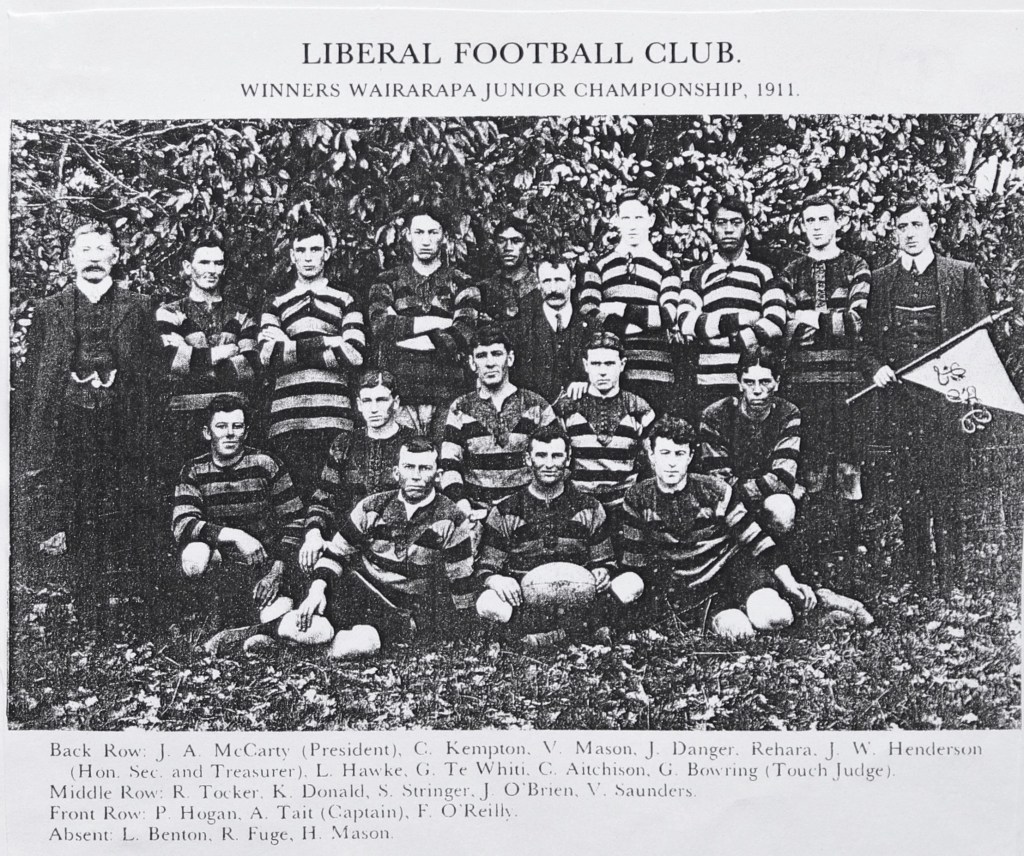

Grandpa Aitchison moved north to Featherston with the rest of the family in 1911. He initially worked with his father in the blacksmith shop, but at some stage before the First World War, he found a job in Carterton selling cars for Gordon Hughan in his Ford car dealership. He owned an Indian motorbike at the time, and he and a friend were reputed to have been the first to ride motorbikes over the Rimutaka Ranges to Wellington. He also joined the Liberal Football Club (rugby) during this period, and in 1911, his team won the Wairarapa Junior Championship.

During this period, he met Dorothy Jones, the stepdaughter of a Lower Hutt dentist. History doesn’t record much detail about this, but they kept in contact through the First World War.

WW I – Gallipoli and Passchendaele

As war broke out in Europe in July 1914, Charles was quick to sign up. His military record shows that he volunteered to enlist with the Ruahine Regiment in Wellington in mid-1914 and underwent military training. On the 27th of October 1914, he was posted to the Wellington Battalion (within the NZ Infantry Brigade) of the New Zealand Expeditionary Forces as a sapper (a combat engineer). He departed Wellington for Egypt in December 1914. Once in Egypt, he was transferred to the newly formed New Zealand Engineers in its No. 1 Field Company. He landed with the ANZAC forces in Gallipoli at Gaba Tepe, colloquially known as ANZAC Cove, on 25 April 1915 and remained there until evacuated with all other forces in January 1916.

He stayed in Egypt through the first half of 1916 and was then posted to the Second Field Engineers based at Étables in France. He remained in France and Belgium for the next two and a half years and was involved in several campaigns on the Western Front, including Passchendaele. This latter campaign has been a byword for the horrors of the Great War since 1917. He was promoted to Lance Corporal in 1917 and later to Corporal. He was discharged on 15 December 1918. Although there is no record of his having been wounded in battle, he did suffer from mustard gas poisoning and spent some time in hospital in the latter part of 1918 with some unspecified “sickness”. The gas poisoning was to affect his health for the remainder of his life and was apparently a contributor to his early death. However, his military record does not acknowledge this.

Mum said that, like most men who returned from the Great War, he had no taste for talking about it, but there are some stories that have survived.

One often related by Mum about his time at Gallipoli involved a pump he maintained in a trench at the head of the beach at ANZAC Cove. There is very little surface water in the cove, so he was charged with setting up and maintaining a pump to supply groundwater to their entrenched troops. This was dug into a large hole, and it seems he spent much of the Gallipoli campaign in this hole. To entertain himself, he would poke his helmet up on the end of his bayonet and await the Turk snipers’ efforts to knock it off. The story doesn’t relate to whether they were successful. He would also barter with his fellow soldiers for access to the hot water in the cooling tank. They would get a hot bath and, occasionally, cheese and onions, which he’d cook in the cooling tank and ‘on-sell’ as ‘Archies Fromage’. The story doesn’t relate to what he got, but it is likely cigarettes’.

Apparently, the only other thing he spoke about was his time on furlough in French villages and his time in London where he and his brother Harry went off to shows like the ‘Maid in the Mountain’.

One mystery Mum records in her ‘Message to Our Grandchildren’ related to an Elizabeth Wilson, who she was taken to see in 1939 as a nine-year-old. Elizabeth was an army nurse who had been torpedoed twice and, on one of those occasions, was found only because of her long, floating hair. She was apparently also the seamstress who stitched Gran’s wedding petticoat. Mum speculated on why she would have done such wonderful stitching for Gran and thought perhaps she had nursed Grandpa Aitchison while he was in a hospital in Europe.

Marriage, selling tractors and farming

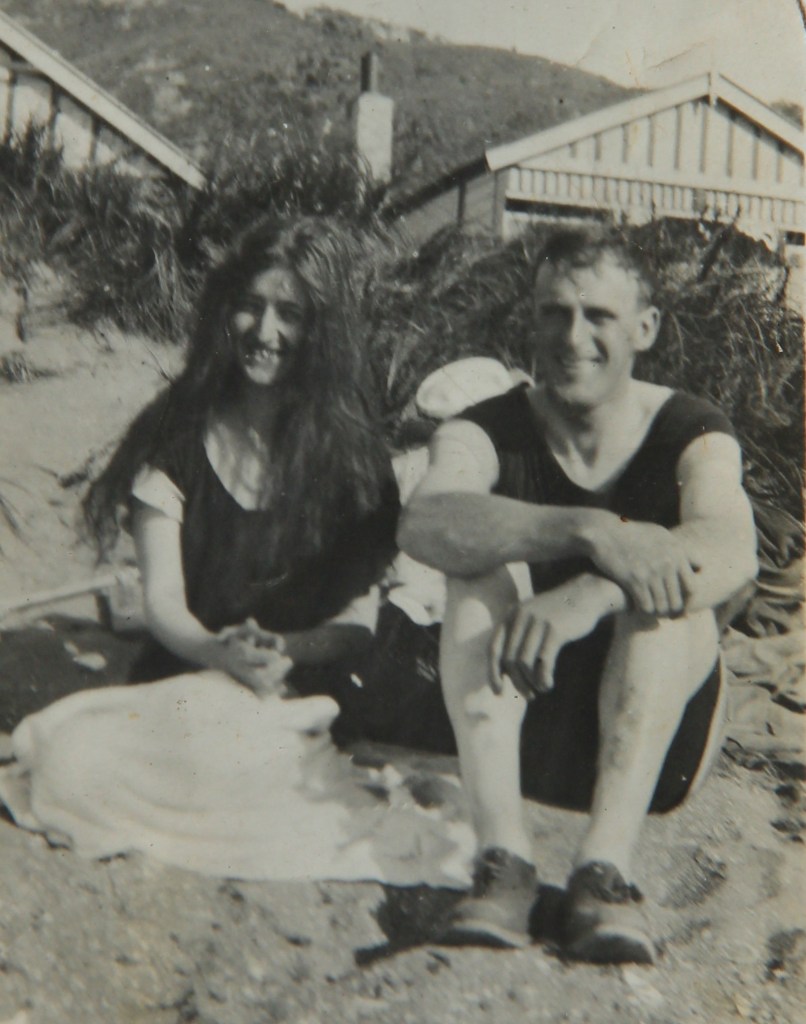

On returning home, Grandpa Aitchison returned to Featherston and possibly to his job with Hughan Motors in Carterton. He also re-connected with Dorothy Jones, and they were married on the 27th of December 1920. At the same time, he accepted an offer from Charlie Todd to work for him in his newly opened motor dealership in Dunedin, so they moved south after their wedding where Grandpa Aitchison began selling tractors around Otago and Southland.

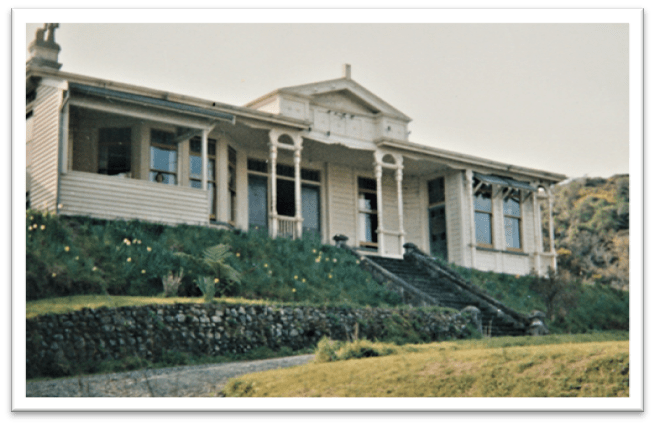

At about the same time, Charlie Todd had also persuaded him to apply for a returned services settlement block in the Maniatoto. This was successful, so they took possession of a property, which they named Clachanburn Station, in 1921. It was a 6,000-acre farm carved out of a previously much larger holding called Puketoi Station, which had been compulsorily acquired for returned serviceman settlement. The land was relatively high country in the upper Taieri catchment, dry and not particularly productive. There were about 2000 acres of alluvial flats and 4000 acres that ran up into the Rough Ridge Range. Grandpa Aitchison stocked the property initially and, with the help of some hired hands, farmed it remotely. He and Gran continued to live in Dunedin, and he continued to sell tractors for Charlie Todd. However, the Government changed the rules and required settlement block holders to reside on the land, so in 1922, Grandpa Aitchison and Gran moved onto the farm.

Children and loss

Their first child, a daughter, was born in late 1922, and their second, also a daughter, was born in early 1925. However, both were to die at the age of 5 and 3 respectively. It is impossible to imagine the impact this must have had on their lives, but somehow, they picked themselves up and got on with life. They remained on Clachanburn, and Mum was born two years later, in 1930.

In 1925, Charlie Todd invited Grandpa Aitchison to join him in a partnership in his motor vehicle sales business, which he had just moved to Wellington. Grandpa Aitchison was apparently tempted, but for reasons unknown, he turned it down, and by the time Mum was born, he was working full-time on the farm.

He continued to tinker with machines – cars, tractors and motorbikes and he was reputed to have had hundreds of vehicle parts, mainly motorbikes, stashed under the pine shelterbelt at Clachanburn. This was a great source of parts for the local bike enthusiasts with whom he had regular contact. The garage owner in Ranfurly was one of them. His name was Ross Curtis, and I met him in 1973 when he was living on Moorea Island in Tahiti (he had married a local and was growing frangipani flowers for the tourist trade on her family land). He talked with some awe about what wonders could be found under that pine shelterbelt if you had the patience to look.

Mum and Gran often said they dreaded the drive over the Pig Route on the way to Dunedin because Grandpa Aitchison would always stop to help some hapless driver who had broken down on the road – apparently a regular occurrence. They could be left for hours in a cold car while Grandpa Aitchison tinkered under the bonnet and gossiped with the driver.

He and Gran remained on Clachanburn for the remainder of his life. In the later half of the 1940s, as Grandpa Aitchison’s health deteriorated, he needed more help to run the farm. Mum left Columba College in April 1946 to pick up some of the load, and with considerable help from her and from people like Laurie Falconer, he stuck with the farm until his death in 1949.

There was always a string of men who worked for him on the farm. However, Laurie Falconer, who worked for them before the War, became a very good friend of the family. He was perhaps a proxy son to Grandpa Aitchison, and Mum felt he was like an older brother to her (he was 9 years older than her). She was always amazed at how tolerant he was of her as a young child, always tagging along behind him on the farm as he worked.

As a member of the Otago Mounted Rifles Territorial Unit before the War, he enlisted in 1941 and joined the 20th Armoured Regiment in Egypt as a 2nd Lieutenant. He was severely wounded in the Battle of Monte Cassino in Italy and returned to New Zealand without his left arm. Laurie kept in touch with Grandpa Aitchison and Gran while he was away in Europe, and during this time, Grandpa Aitchison arranged for him to take over the lease of Puketiri Run when he returned home. This was two farms up the Maniatoto Valley from Clachanburn. He moved onto this property as soon as he came out of hospital and set about learning how to farm with only one arm – and that he did. When I met him in the late 1960s, I was in awe of what he could do with that one arm – rolling a cigarette was one feat that I recall, but there were no tasks he couldn’t do on the farm, including shearing.

When he first came to the Maniatoto in the mid-1930s, he fell in love with it, particularly Clachanburn. So, he always reminded Gran and Grandpa Aitchison that if ever they wanted to sell, he would love to buy Clachanburn. This he did when Gran offered him the farm in the late 1950s. Some of his family remain there to this day. His daughter-in-law Jane has done an incredible job in developing the garden around the homestead, and today, it is regarded as a Garden of National Significance and receives hundreds of visitors each year.

It’s hard to know whether Grandpa Aitchison was a good farmer, but he apparently loved the land and enjoyed nothing more than channelling water from the water race to flood-irrigate areas of the flats. He could spend many happy hours with a spade in his hand and trickling water at his feet. He was not a gardener, however. Mum recalls Gran asking him once to put some sheep manure from under the woolshed on the vegetable garden. He dutifully did this – with a layer nearly a foot deep. In that dry climate, it was some years before that particular garden would grow anything, but when it finally did, it flourished.

Mum described Grandpa Aitchison as a very balanced and, mostly, a calm and cheerful person. Despite the horrors he would have had to contend with in the War, and despite the loss of his first two children at an early age, he seemed to have quietly come to terms with these things in his mind. He seemed to have dealt with them like so many at the time and simply shut them out and didn’t talk about them. Neither, it seems, did he lose his sense of humour. He seemed to delight in embarrassing his young daughter, and his favourite trick was using big words when in company, which Mum found hugely embarrassing as a girl.

He had also inherited his mother’s sense of their elevated position in life and the sense of obligation that this entailed. Mum said that he was far from a snob, but he did insist that she remember her position and he expected that she would behave accordingly.

As might be expected for a farmer, he was staunchly conservative in his political views. It must then have been a struggle when his older sister Vera, married a ‘leftie’ in 1918. Valance Llewellyn was a Wellington ‘wharfie’ and a union organiser and was staunchly left in his political views. His son Sam Llewellyn, once said to me that Charlie would often refuse to visit his sister when in Wellington for fear of getting into a political argument with Valance. Gran would still go, and so she maintained the family bond.

Grandpa Aitchison. died on 26 November 1949 after a long period of illness, some 28 days before Mum and Dad’s wedding.

Gran – Dorothy Lilian Aitchison, nee Jones

My Grandmother was somewhat of an enigma to me. When I was a child, she seemed quite stern and very prim and proper.

I don’t recall ever seeing her angry or laughing out loud; she seemed always to be completely contained. As I got to know her, I began to see that she could show pleasure in things and also displeasure and that she loved her grandchildren completely, if not as effusively as Nan, our father’s mother. Given the trauma that she had gone through in her life, it was little wonder that she was emotionally contained, but I didn’t know this at the time.

Her heritage

Her heritage was predominantly English with a smattering of Scottish. Her grandfather on her father’s side, William Jones (1824-1896), was from Kent and her grandmother, Emma Broderick (1831-1909), was from Middlesex. On her mother’s side, her grandfather was Thomas Burt (1818-1888) from Launceston, Summerset, and her grandmother, Elizabeth Wilkie (1826-1916) was from Perthshire in Scotland. All four grandparents arrived in New Zealand in the early 1840s, and all settled in the Hutt Valley.

Her father, Ernest Broderick Jones (1867-1901) was born and grew up in the Hutt Valley and became a teacher there.

Her mother, Blanche Beatrice Rishworth (nee Burt) (1868-1930), was also born and grew up in the Hutt. She came from a large family of eleven who were market gardeners and who owned land in the Lower Hutt. Her older sister Catherine Cleland (nee Burt), moved to Taranaki with her husband Robert and their nine children in 1893. She was 43 at the time. They bought a dairy farm at Kaponga out of Stratford, where they milked 220 cows by hand. Soon after, her husband died, leaving her to bring up the children and run the farm on her own. This she did, apparently with some success. Gran recalled having holidays there with her cousins, milking cows and warming her feet in fresh cowpats. As a child, I struggled to reconcile this latter story with my grandmother, who I felt would scarcely let herself be so down to earth. It was, however, the beginning of an understanding that she once had a lighter, more carefree life.

Losing a father

Gran was born on the 3rd of March 1894. When she was 5 years old, her father was diagnosed with tuberculosis. He sold the family home and went off to California in 1899 to pursue a new treatment. He wrote often to his then five-year-old daughter while he was away, but the treatment did not work, and by 1901, he had died, leaving behind a widow and two small children.

Her mother, Blanche, later married Edward Percival Rishworth, the son of a Christchurch minister and a prominent dentist in the Hutt Valley at the time. Edward’s first wife, Georgina Patience (nee Lackland), had died, leaving him with two sons, Eric and Cyril, who were just a few years older than Dorothy and her brother Lestock. Edward was a prominent resident in the Hutt – he was Mayor of the Hutt Valley from 1918 to 1921, and he unsuccessfully stood for Parliament for the Reform Party (a forerunner of the National Party) in the Hutt Valley Electorate in the 1919 election. He was well respected within the dental fraternity and was Chair of the NZ Dental Assoc. for some years. He was also a very capable artist and painter. However, as a stepfather, Gran and Lestock (Uncle Ticka as we know him) did not have many positive things to say about him. Apparently, Gran was treated well as a new daughter, but Uncle Ticka suffered some considerable abuse.

She grew up then in a home that, if not entirely happy, was well-off and had well-respected parents. She was very much a city girl and enjoyed her urban upbringing; she was apparently a competent pianist and opera singer, although, sadly, she’d given both of these up by the time I came along. I only recall hearing her sing in church, and she did that with gusto.

Marriage and farming

Gran met Charlie Aitchison sometime before the First World War, kept in touch during the War and re-connected in 1918 when Grandpa Aitchison returned from Europe in December 1918. They married in December 1920 and moved to Dunedin where Grandpa Aitchison was working as a car and tractor salesman for Todd Motors.

We can only guess how she felt when the Government of the time determined that they would have to move onto the farm in the Maniatoto to retain it. However, when passing through the area sometime before, she once observed how dreadful it would be to live there. Nonetheless, they made the move, intending that it be temporary until they could sell the farm and Grandpa Aitchison could take up Charlie Todd’s offer of a job in Wellington. So, here we have this city girl from the Hutt Valley, marooned in the middle of a dry and empty Otago landscape, some miles from her nearest neighbours, and on her own during the week while her husband was away selling tractors. As Mum described in her ‘Message to Our Grandchildren’:

“Washing with a copper on an outside fire, no trees, no birds, only an aching silence. There was a horse and cart, but I doubt she would have known how to use it, and where would she have gone?”

Even grocery shopping was a vastly different experience from what she was used to. Almost all supplies were ordered from Dunedin through their stock and station agent Dalgety’s, and generally on a six-monthly basis. Initially, she had little idea about quantities and said she made a few mistakes – usually over-ordering rather than under. I recall Mum using, around 1978, the last of a very large bottle of vanilla essence that she had bought in the mid 1920’s.

Losing two daughters and raising one

She persevered; by 1925, they had two young daughters to care for. Dorothy Lorraine was born on the 28th of December 1922, and Rosalie Blanche on the 19th of January 1925. Grandpa Aitchison was still selling tractors as the farm was not, at that time, capable of providing a living for them.

By August 1928, both children were dead; both victims of meningitis. Rosalie died in December 1927, and Lorraine eight months later, in August 1928. For even the staunchest of hearts, this would have been catastrophic. On one of the few occasions she spoke of it, Mum asked her years later how she coped. She apparently made much of the fact that everyone in the district was in the same situation. This, of course, was not true, but it did show how she had reconciled it in her mind.

She felt she had to be strong for her third daughter Beverly, born two years later, and strong she was. Like her husband, she learned how to lock up the unthinkable and bury it deep enough to not be reminded of it except on the rarest of occasions. Perhaps she felt that if this was at the cost of spontaneity and happiness, it was a cost she was willing to bear. She may never have been a spontaneous and extroverted person; we will never know, but it was clearly a means of survival for her.

She and Charles remained on Clachanburn through Mum’s childhood. When Grandpa Aitchison eventually gave up selling tractors and became a full-time farmer, Gran fulfilled the role of a run-holder’s wife. In her way, she found a niche for herself. However, she was apparently never able to feel like she completely belonged. In all the years that she was on Clachanburn, she never went to either end of the property, and while she had many friends, she could apparently never really feel at ease. At a celebration of VE Day, Mum remembers her mother being teased by Mrs Keegan at the Patearoa Hotel, who said, “…come on Dorothy, forget you are a lady for once”. Perhaps she was conscious of her contained emotions because Mum recalls Gran often telling her how blighted she felt when she once overheard a relative say, “…Dorothy is such a sensible girl!”.

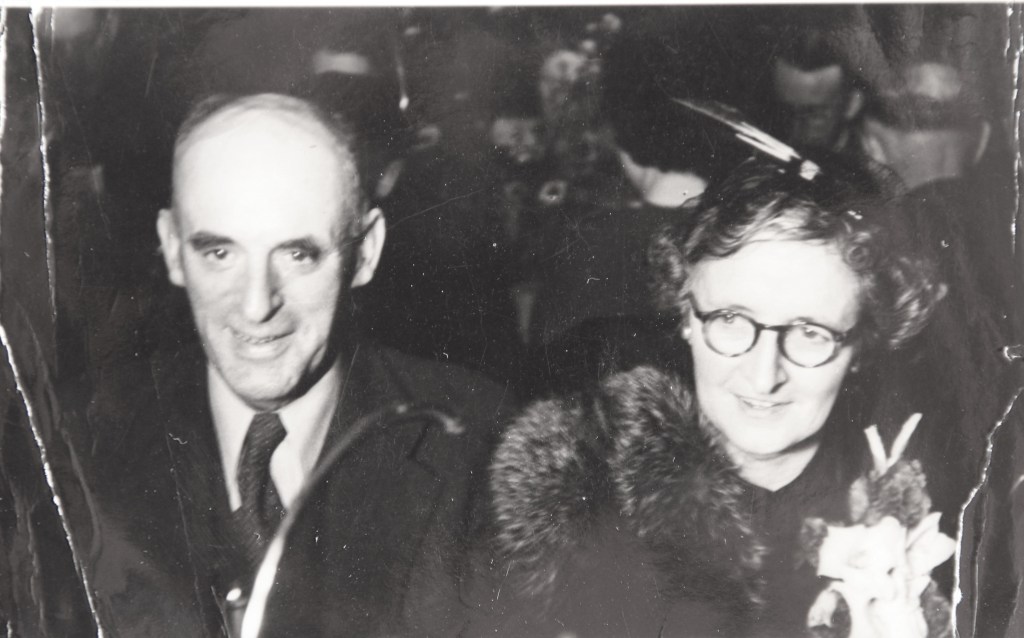

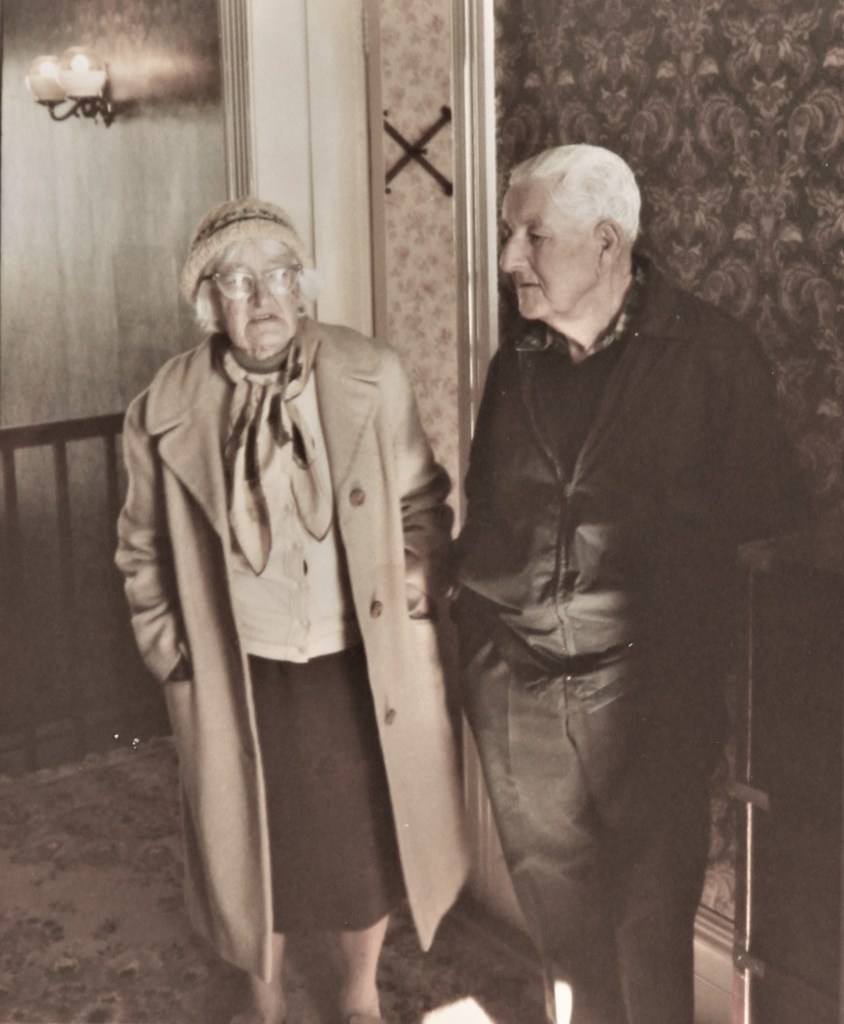

Back to Wellington

When Grandpa Aitchison died in 1949, a manager was employed to run the farm, and Gran moved back to Wellington to live in one of her late mother-in-law’s houses at 44 Jubilee Road in Khandallah. Her brother, Lestock Jones, who had never married and lived in Wellington throughout most of his life, moved in with her. They lived together for the rest of their lives.

Mum noted how Gran flowered when she moved back to Wellington, in sharp contrast to her dogged determination toward life in the Maniatoto. She enjoyed socialising with her sisters-in-law, joined the local church (possibly more because it provided an opportunity for social networking than because of a religious conviction), formed a Scrabble group and dabbled in antiques.

When I was around seven years old, John and I lived with her and Uncle Ticka for a time. The local school at Kaharoa closed after the sole teacher retired, and John and I were sent off to Wellington to attend school. I’m not sure why it was John and me, but perhaps we were considered the slower two of the family, as Kay and Pip remained home on home-schooling. I spent six months there, and John stayed for a full year. It was a wonderful experience and exposed me to what urban life could be like. John thrived and recalled it as a very happy time when he made many friends and learned to sail on Port Nicholson Harbour. The only achievement of mine that I remember was learning to ride a bike on my friend Oliver Robb’s tennis court.

Her final years

In 1968, they sold the house on Jubilee Road and moved into a home that Mum and Dad had built for them in Elgin Place, at Red Beach, Whangaparaoa. I don’t know whether this was because Gran and Ticka wanted to move closer to our family or because Mum and Dad felt they needed to be closer as they aged, but either way, it worked, at least for a time. They still had their independence, and we got to spend a good deal more time with them. However, as they aged and needed closer care, even this proved too remote. Mum and Dad had, in 1977, built their own house at Kowhai Terrace in Leigh, so they bought a section across the road and put on a pre-built house for Gran and Ticka. They moved into this in 1979 and set about developing yet another garden.

I recall that Gran seemed very happy here. She was in her own home and close to her daughter and son-in-law. She also had more regular contact with her grandchildren and a growing pack of great-grandchildren. She maintained good health right up to her death on the 11th of November 1982. She was in Warkworth having her hair done on the day she died. Like everything else she did in life, she departed it without any fuss.

Lestock Jones

Uncle Ticka was born in Wellington on the 13th of June 1898 and was Gran’s only sibling. He was very close to her, a closeness perhaps strengthened by their having grown up as step-children in a home where he, at least, was not greatly welcomed.

He always struck me as a quiet and unassuming man who was always there as an adjunct to Gran’s life but never someone who was his own person. This was perhaps a little unfair, as he did have his own life, his own interests and his own history. He just didn’t assert them. As a 19-year-old, he worked as a farm hand for his cousin, Robert Cleland, on the dairy farm at Kaponga. He enlisted with the Army in 1918, but as the war nearing an end, he did not go to Europe. It is possible that he remained in a civilian administrative role with the Army between the First and Second World Wars, but he volunteered for service in 1939 as a forty-one-year-old and joined the New Zealand Air Force. He entered the Pacific War, was posted to Vanuatu, and spent time at an airfield in Luganville on Espiritu Santo. His claim to fame there was to be the first person to successfully grow tomatoes there – no mean feat given the climate. Many years later, Yvonne and I went there on a diving trip and explored the old airfield and base. Little remained but for building foundations and some of the tarmac, and all was covered with vibrant vegetation. Thankfully, the scars of war do not last forever.

He remained working for the Armed Services as a clerk after the War until the early 1960s, when he left to join Dominion Motors in Wellington. This was a little ironic, as he had little sense for mechanical things and for cars in particular. However, he loved his new Morris 1100 and kept it until after he finally had to give up his licence. Even after that, he snuck off once for a drive to the general store in Leigh. He parked it on the hill opposite the shop but didn’t engage the handbrake. The car proceeded down the road, toward the wharf, into a power pole and over a bank. It was written off, and some considerable liabilities arose from the damage to the power pole, none of which was covered by insurance. That, however, was probably about the most risqué thing my uncle ever did.

One of his great loves and a great skill was gardening, perhaps something he had inherited from his mother’s market gardening family. He largely kept him and Gran in vegetables when they lived in Khandallah and at Whangaparaoa, and their flower gardens were always immaculate. Even at Leigh, where the topsoil had been scraped clear from the heavy clay, he managed to make things thrive. Dahlias were his specialty, but anything was good for him, provided it had lots of colour.

He never married, and although there were vague stories of his having girlfriends, it is possible that he was gay. This was never questioned or discussed, which is not unusual for the time, but it does strike me as a little sad that if true, he could never truly express himself.

He remained in Mum’s care for a time after Gran died, then moved into Ranfurly Village where he died on the 24th of August 1984.

Footnote:

- See Dispatch Note, Scrapbook 5, page 2, noting a dispatch from Grandpa Aitchison in Cairo to Gran in June 1940. This would have accompanied a letter or similar which we don’t have.

Leave a comment