The First Pacific Cruise

We need to step back in time to the early 1970s, when they began planning their first Pacific cruise. It is quite likely that they had been talking about this long before, but it was while they were on Waiti that the plans really began to crystallise. This was probably driven by Mum’s longstanding determination to go to sea and their realisation that the Waiti experience would have its limits.

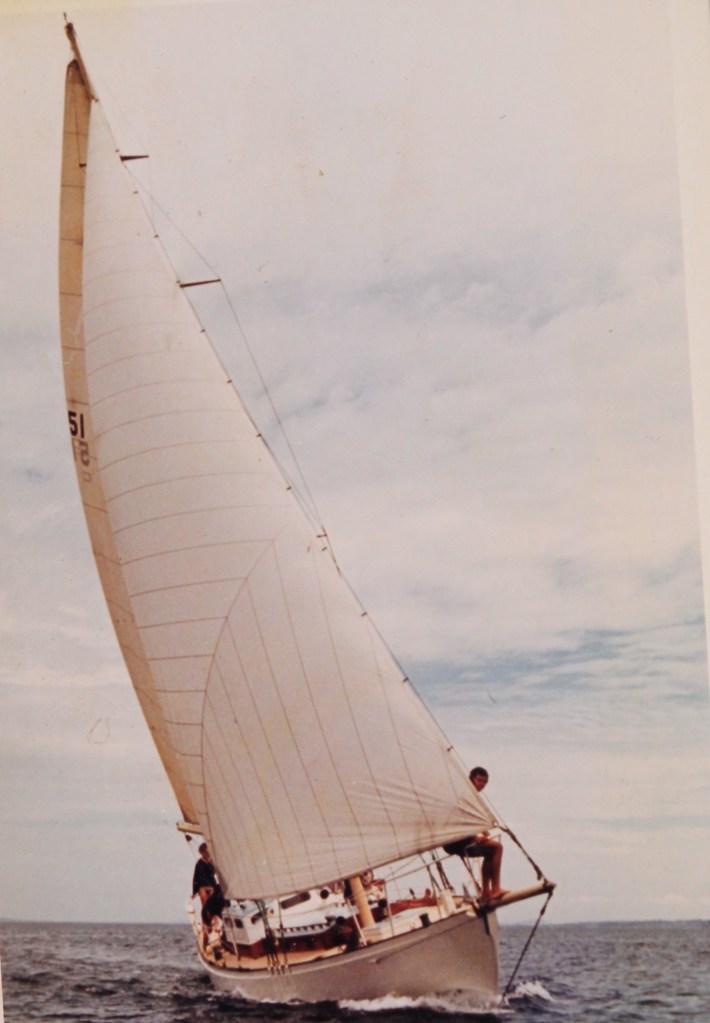

Cecilene, the yacht they had bought while still on Waiheke, was a solid forty-foot Bermudan cutter built from double diagonal Kauri and with a full keel. She had had a good track record in offshore sailing with Philip Houghton, an Otago University medical professor, who sailed her around New Zealand under the name of Murihiku in 1966-67 and wrote a book about it. Dad, who had a good eye for a boat, was convinced of her seaworthiness. Nonetheless, she still needed some work to bring her up to standard for offshore cruising, so he set to work on her while they were still on Waiti. It was another two years before they decided to quit the farm and begin serious plans to go to sea.

Once they left Waiti, they moved into an apartment in Remuera. Mum got a job with the Post Office in their telephone exchange. Somehow, she never got to direct calls, but she did travel all around Auckland to support technicians installing PABX systems (like mini telephone exchanges) in businesses in the region.

Dad initially got a job with John Burns, a boat chandlery in town, but he then joined the Port Agricultural Service where he spent his days checking ships, planes and their passengers to ensure they were biosecurity compliant.

Cecilene was kept on a pile mooring up the Wade River in Silverdale. This involved some travel for Dad as he still had much work to do on her. So, they bought a house in Okura that overlooked the estuary. This was a small and basic fibrolite clad bach, but it was on a magnificent site, and it suited them well. Photos show its transition in the short time they were there, from a bare box on an empty section to a cosy house in a well planted garden. Dad’s sister Gwen later built a house just down the road and when Mum and Dad left for the Pacific, they handed the house over to Nan and Grandpa who were to finally move out of their Exeter Road home.

Toward the end of 1972, Kay returned from South Africa where she had been for eighteen months, with a stint in Europe and behind the iron curtain in the USSR, in between. She bought with her, her new man whom she had met in the East London Yacht Club. Malcolm had grown up in the Transkei, boarded at school in Queenstown in the hills inland from East London, had a stint in the South African Air Force and eventually found his way to the sea in East London. He learned to sail here in the Indian Ocean, which rolled untamed, along that southern African coast. So, he was a dedicated and very competitive sailor and could speak fluent Xhosa – Kay was smitten. They were married in December 1972 in Auckland, honeymooned with the family aboard Cecilene at Great Barrier and then returned to East London.

Mum and Dad had suggested that I join them on their cruise as I had just finished a job on a farm out of Methven. I leapt at the chance and joined them for the last six weeks to help with the final preparations. Everything about the trip had been meticulously planned. There were risks of course. Small boat cruising was still relatively new and no systems were in place to affect a rescue if we got into trouble. Dad had to make sure then, that we had the means to survive on our own if things went bad. And this he did, but thankfully it was never really tested.

Departure day was set for the 5th of May 1973. We had been tied up alongside Marsden wharf for a couple of weeks before, making final purchases of supplies, and getting the new self-steering system (Hori as we called him) installed. This had been designed by Bill Belcher, a renowned ocean sailor who had once been wrecked on the Great Barrier Reef. He was living on Waiheke when we met him, and he took a particular interest in our venture and spent some time with us before we set sail. He looked a little like something the cat had dragged in, but he was a delightful, intelligent man with a dry, laconic wit whose company I enjoyed a great deal.

During this time, a flotilla of boats was gathering at Marsden Wharf to sail off to Mururoa to protest the testing of atomic weapons by the French. Dad would never have taken most of the boats into the Hauraki Gulf, let alone off to Mururoa, and their crews comprised a mixed bag of genuine sailors and passionate anti-nuclear protesters who’d never been to sea. However, there was no doubting their passion for the antinuclear cause. They tried to persuade Mum and Dad to join them, but Dad politely declined.

As far as I’m aware, they all came back in one piece, but a young British solo sailor tied up behind us at Marsden Wharf in his tiny eighteen-foot yacht was not so lucky. He was reported lost in the Tasman Sea on a passage from Auckland to Sydney and was never found.

The Mururoa protest fleet got quite a bit of media attention, but I was surprised to find that so did we. I guess it was unusual enough and had sufficient risk attached to it to make it a worthy human interest story for the papers. But all this added to the growing excitement as we approached departure day. There was quite a crowd there, some of whom (Nan in particular) were convinced that we would never be seen again. However, my only enduring memory of that day was sailing out past Bean Rock Light and watching a line of traffic slowly crawling along Tamaki Drive as people drove home from work. I felt eternally grateful that I was not among them.

We settled into a quiet routine of watches, eating, reading books and sleeping, and we rolled along on a good southwest wind making around 100 miles a day. Mum went through a few days of seasickness, and still she insisted on cooking meals as she felt that that was her role. She almost always suffered from seasickness on the first few days of going to sea and whenever it got rough. However, it never dented her enthusiasm for sailing – she just got on with it.

Twenty-one days out, we made our first landfall at Tubuai in the Austral Islands to the southwest of Papeete. We sailed past in the evening with lights blinking in the villages and the smell of cooking fires on the air. We longed to go ashore, but the rules required that we couldn’t and that we must formally enter French Polynesia in Papeete. Four days later, we passed through the passage in the reef at Papeete and tied up, stern-to, on the waterfront in town.

Given the tense political climate between New Zealand and France over the nuclear testing, we were mildly anxious about our reception. We needn’t have worried. If anything, they made an extra effort to look after us. Formalities were over quickly, in no time, the French military had taken Hori off the stern (he had suffered some damage during a heavy blow to the south) and had him repaired. A French couple, one of Mum’s friends had referred us to, Louis and Havre’s Darer and their delightful teenage daughter Genevieve, took us into their home, drove us about the island and generally entertained us over the next week. Enduring memories recorded in Mum’s ‘The Mates Journal’ were of course the hospitality but also the French baguettes (baked by a Chinese man), singing from the church across the road from our mooring, vibrant vegetation, and the smells of a tropical climate.

While here, we met a British couple, immigrants to New Zealand, who had arrived in their yacht two days before us. He was eighty years old and she was seventy-eight. Just before they left New Zealand, she had a stroke, and her family were a little relieved as they thought it would mean their trip would be off. However, she would have none of it. By the time we met them, she still had quite a limp and a slur, but was otherwise well. They left for Hawaii before us and when we got to Hilo, we asked at the yacht club about their whereabouts. “Oh” they said. “Yes, that was the lady who sprained her ankle while surfing. No! They’re just fine and have gone on to Honolulu”. They later went on to North America and down the coast to Tierra del Fuego where they spent a year getting their boat fixed after fetching up on some rocks. Five years later, they returned to New Zealand, still fit and well, and she, with not so much as a limp.

We went on through the chain of islands that make up Tahiti, we were entertained and feasted by the locals, and we soaked up the delights of cruising in a warm tropical climate. In her journal, Mum was effusive in her enthusiasm for the place and its people. It was the first time either of them had been north of the 35th parallel, so the warmth alone was a delight for her. But also, she lapped up the differentness. Dad, too, enjoyed the new experiences and felt a degree of satisfaction from having safely navigated us to this place. He became increasingly confident in his boat and in his ability to safely navigate it and its crew through the Pacific. As a consequence, he began to relax. Predictably, he started to get anxious again as we approached departure for Hawaii, but this soon passed as we took to sea.

As we passed through the Doldrums to the south of the Equator, we were set upon by what seemed like an endless succession of deluges that came up out of the southeast – black thunderous looking things in an otherwise blue and windless sky. We never knew whether they would bring with them wind or just rain until they hit us. Dad would insist on dropping sails just in case, which frustrated me hugely, but I had to admit that it would not have been good to have had sails up when some of them came through. Most, though, contained just rain. This was an excellent opportunity to get up on deck with a bar of soap. The trick was to get soaped up and rinsed off before the rain stopped, which it did with incredible suddenness.

After we crossed the Equator, we were confronted with cyclone Doreen which had danced all over the lower latitudes of the north-eastern Pacific after swinging off the coast of Mexico. Within a few hours it moved from eighty odd miles to the north of us to eighty odd miles to the south, but somehow, we missed the worst of it, and we rolled on west toward Hilo on the huge swells that it had kicked up. Here, north of the equator, the water changed from deep aqua blue to a teal green.

While horrifying to modern day navigators, we never kept watch through the night unless we were in shipping lanes or known fishing grounds. Hori would obediently sail us through the night; if the wind shifted, we could feel it instantly in the change in movement of the boat. However, as we approached Hilo, we entered a shipping lane, so we kept a watch. This usually involved tucking down in the doghouse where you could read a book in comfort and from where you could pop your head up every fifteen minutes to scan the horizon. On one such watch, I was propped up with a book on my lap when I suddenly became conscious of a thrumming noise coming through the hull. I leapt up into the cockpit; a ship was not two-hundred metres off our starboard beam. It had come up behind us in the preceding fifteen minutes and was directly abeam. Dad came up to stand beside me in the cockpit where we both watched its lights disappearing ahead, and we both thought but did not say that but for 200 metres, we might well have been in a bit of a mess.

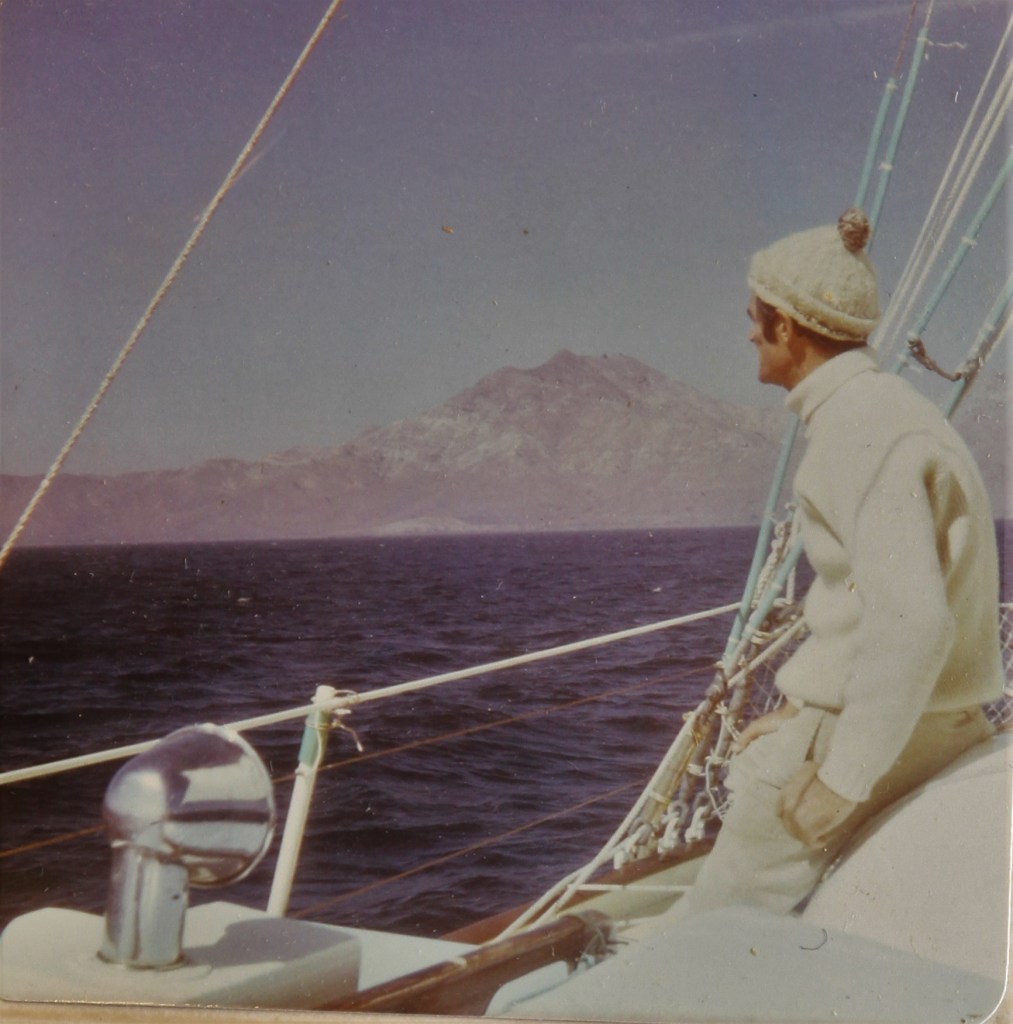

On the 26th day at sea, the chief navigator told us that we should be able to see the Big Island from about eleven in the morning. I spent all day scanning the horizon but could see nothing. By evening, even the navigator had begun to doubt his skills, so we hove-too, and sat out the night. In the morning, I could still see nothing to the west. But then suddenly, way up high, several degrees above where I’d been looking, I saw a splash of pink snow lit up by the rising sun. At 13,800 feet, Mauna Kea’s snow-capped peak confirmed that the navigator was bang on target.

Mum’s journal records her enthusiasm for Hilo and the Big Island. We were embraced by the local boating community and invited to all sorts of dinners and events. I was invited out on several diving and fishing trips, and we spent several days exploring the island by car.

The town was a fructivore’s paradise as there was a wide belt of land between the water and the town that used to be in housing but was now empty but for the fruit trees that continued to produce prolifically. The houses had been removed after a Chilean tsunami destroyed the town in 1960, and it was rebuilt on higher ground. Among the fruit were avocados which we had never seen before. They were a real hit with Mum, but Dad and I were not so enamoured.

Mum’s journal makes much of letters from home at the time. Today, we take for granted our ability to keep regular contact with loved ones regardless of where we are or where they are in the world. Then, there was no internet or email – it was strictly snail mail. She records great disappointment when there was no mail (usually because the local post office couldn’t find it), and great delight when we’d come away with a great bundle of letters. We’d sit in the cockpit or down below and devour them – and share the stories they conveyed before others had had time to read them.

After our stay in Hilo, we island-hopped north to Honolulu. Lahaina on Maui was our favourite. Conversely, Moloka’i was ghastly, as it was just one big Dole pineapple plantation. A dinghy full of pineapples from the barge loading dock in Kaunakakai only slightly softened the bad impression.

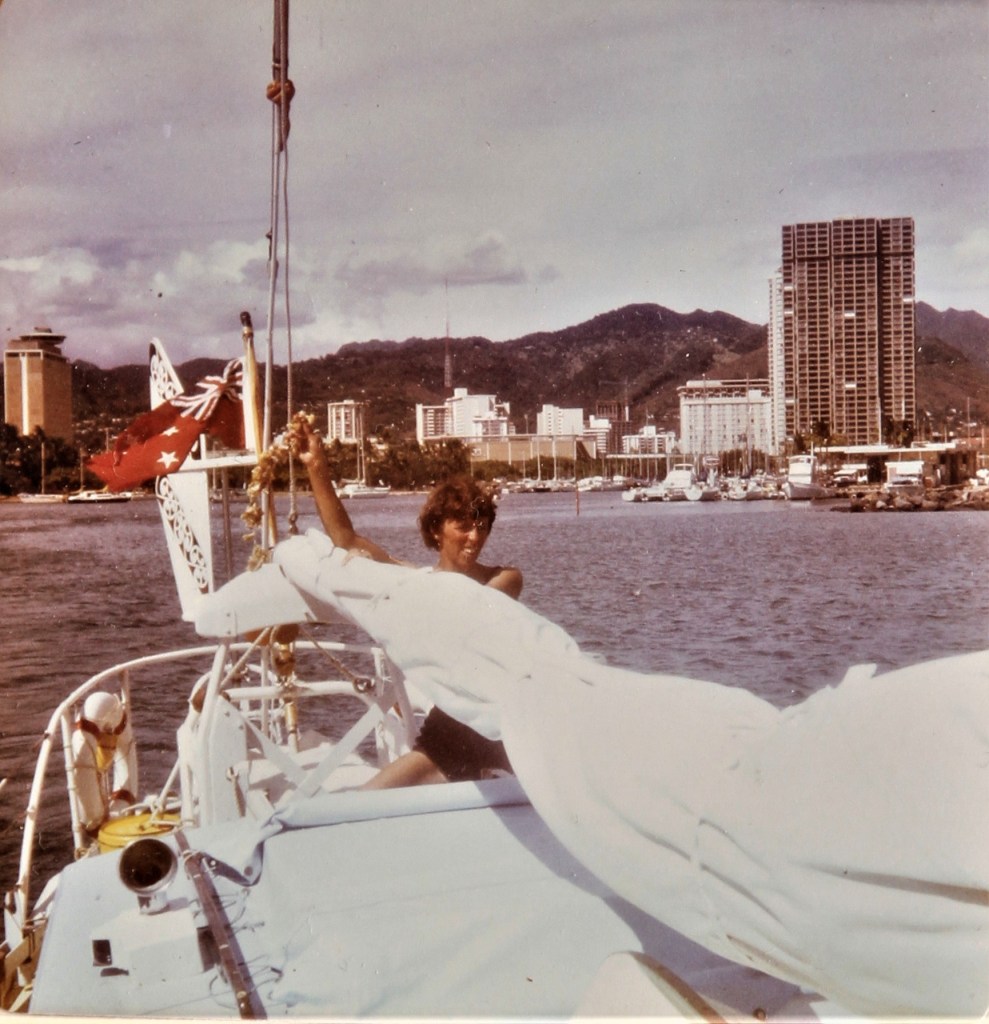

Again, we were treated incredibly well at the Ala Wai Marina in Honolulu. We tied up right outside the clubhouse and were regularly hosted there over the next week or so, taken for trips around the island and shown the sights of Honolulu and Waikiki. I was welcomed into the yachting fraternity’s teen gang; we ate banana splits on the top of the Ilikai Hotel, smoked dope (first for me) on the beach at Waikiki and hung out around the ice machine at the yacht club. I water skied in Pearl Harbour and scuba dived up the coast (again, both firsts for me), so I could have happily stayed there forever. However, I had a plane ticket to London, so I reluctantly took my leave.

Mum and Dad stayed on for a month, enjoying the hospitality of the Ala Wai Yacht Club and exploring Honolulu and the wider Oahu, but they soon felt the urge to move on. They set off northbound for Los Angeles in the middle of September. The plan was to go north on the northeast trade winds, get over the top of the north Pacific high, and then swing east once the westerlies kicked in. The trades were non-existent and what wind they had was on the nose, so progress was very slow.

Mum records lots of shipping throughout much of this trip—from Navy destroyers on exercise to huge oil supertankers. They maintained watches here, but surprisingly, after our experience approaching Hilo, they reduced horizon scans to a half-hour.

Mum savoured the last of the warm weather and looked forward to the cold north with some dread. When it did come, with the cold Californian current, she wrapped up in lots of jerseys and Dad opined that they should be anchored in Nagle’s Cove instead of “buggerising around in the North Pacific”. They made progress, more or less, along their chosen course, and got as far north as the 37th parallel. They approached the California coast in heavy fog and heard surf on Santa Rosa Island well before they saw it, and then only when they stopped the motor to have lunch. The fog finally lifted, and they anchored in Smuggler’s Cove on Santa Cruz Island under a clear sky. They drank the last of Kay and Malcolm’s wedding champagne and watched pelicans dive like gannets into a school of fish. Perhaps not quite Nagle’s Cove, but it was pretty good!

On the 18th of October 1973, after 50 days at sea, they motored into Marina Del Rey. There were no journal entries for the next week, but life must have been a whirlwind. They decided to sell Cecilene, buy a camper, and travel through the USA, so they set about making that happen. They had contacted Peggy Slater, a yacht broker in the marina, and began to look around for work and a place to live.

Looking back on this experience, Mum would cherish every bit (perhaps except for those days of seasickness). It was pure adventure. She had her best mate with whom she had utter confidence, trusting entirely that he would get them safely through the experience, and she got to see places and meet people that she would not otherwise have done. For his part, Dad felt a great sense of satisfaction having successfully completed the venture, and he was genuinely delighted with the places they went and the people they met, but there were times when he felt the pressure of having to get us through in one piece and this would temper the experience a little for him.

North America

They had already applied for and got Green Cards in Hawaii, so they could start work immediately. They moved into an apartment in late October—223, Building R, Oakwood Gardens, Via Marina 4109, right across the road from the marina—and Mum began working at Fanny’s Restaurant in the marina. Dad began working as an in-demand casual boat maintenance man.

This was to be a giddying period of discovery for both. They were surprised at how well they took to apartment life, living close to boats and being within walking distance of their work and most of what they needed. But it was the people that they enjoyed more than anything. It was ethnically, culturally and economically much more diverse than the relatively monochrome and conservative community they had come from. People were perhaps more tolerant of difference, but they were very much more individualistic and driven to succeed than the New Zealanders they were used to. There were also an incredible array of characters that Mum delighted in observing. There are many little vignettes in her journal of people she met, reflecting her enthusiasm for people watching.

‘A tee shirt inhabited by a very large torso, reading on the front ‘I AM QUEER’ and on the back ‘I MAKE LOVELY PEANUT BUTTER SANDWICHES’’.

‘Katie; the lovely little Jewish waitress with two children, an ex-husband and a degree, and still studying philosophy and art history.’

‘Joy; sharp, abrasive, defensive, and aggressive, with a music degree and playing flute in the LA Symphony Orchestra.’

Here too, she met Hal Holbrook, a Hollywood actor who, I suspect, was quite smitten by her. He certainly charmed her and would engage her in long conversations while she was supposed to be waiting tables. She spoke of him often in later life, especially when he appeared in a movie she was watching.

They sold Cecilene to a Hollywood filmmaker, Ellis Rose. Rose had grown up in the South in a poor black family, but he had made good in Hollywood and somehow acquired a love for boats. It was apparently a good sale and probably one of the few times Dad had made money on a boat. She was later to be meticulously restored by a subsequent owner, back to her original specifications and complete with a gaffed ketch rig. As far as I know, she remains in Los Angeles to this day.

They bought a VW camper, which they named Bessy, resigned their jobs, picked Pip up from LAX (he had just finished a farming job in West Otago), and set off to discover America. It was the middle of March with the vestiges of winter still hanging on the hills, so south they went – to San Diego, across into Southern Arizona and then to the Grand Canyon. They then looped back toward California via Death Valley, up through the Sierra Nevada’s near Mount Whitney, and into Yosemite National Park.

After a short stop back in LA, hoping the winter would retreat before them, they set off north following the coast – through the Big Sur to Salinas of Steinbeck fame, Monterey, and on to San Francisco. Then up into Oregon, following the coast to Portland. Here, they left the coast and followed the Columbia River to Chelan, Washington.

They travelled little more than one hundred miles a day, camping in Forest Service or other Federal and state campgrounds, of which the US has an abundance. These were then, and are probably still, mostly basic, simple affairs generally located in delightful settings. These campgrounds fitted their needs well, but they would periodically ‘lash out’ and stay at a KOA campground where they could get a hot shower and do some washing.

Despite their relatively slow pace, it seemed that the winter retreat wasn’t happening as fast as they might have liked, as Mum’s journal records many foggy, wet and cold days. This is a feature of this coast where the cold south-setting current routinely creates cold foggy conditions and regular rainfall, particularly further north in Oregon and Washington. However, the temperature rockets up a few miles inland, and annual rainfall drops dramatically. There seemed to be some debate about whether they should retreat inland well before Portland, but in the end, they pushed on up the coast.

In Chelan, however, the sky was clear and seemed not so cold and damp. They were taken with this country, nestled under the Cascade Mountains, not unlike Otago and with apple orchards for miles. They arranged work on an orchard owned by Joe and Gloria Bennett, on the shores of Lake Chelan for later in June, and then set off over Stevens Pass toward Seattle. Skirting the city, they entered Canada and pushed on to Vancouver. After a brief stay with an Aitchison relative (Marion), they crossed over to Vancouver Island. This was quite a revelation for Mum and Dad, and it was the one place Dad had seen so far that could almost persuade him to forsake his homeland. While it was quite different from what they had expected, it was every bit as beautiful.

They had for years talked about sailing up the inland passage from Vancouver to Prince Rupert. Now, in their ‘four-wheeled boat,’ they were close to achieving this. Looking at the currents in the Seymour Narrows, they were a little relieved they were not on the water in a smaller boat, but on a wet and dreary morning they boarded a ferry and set off north through the inland passage to Prince Rupert. Vast rafts of logs, mist, rain and endless forests dominated the view. Prince Rupert was closed on a Sunday and looked distinctly damp and dreary. So, they set off inland, hoping for some dryer if not warmer weather.

They drove through the Rockies and into Jasper National Park where the photo in Figure 197 was taken of Mum pumping water into a bucket to do some washing. Washing clothes in strange places was a feature of travelling for Mum. She loved crisp, clean clothes, but I suspect she also liked the task, especially where it could be done in exotic places. Later, when they were in the Great Smoky Mountains, she came across this little piece on an interpretation panel at an historic homestead – something that I suspect she could relate to:

A note a pioneer mother wrote her daughter telling her how to wash clothes.

- Build a fire in back yard to heat kettle of rainwater.

- Set tubs so smoke won’t blow in eyes if wind present.

- Shave whole cake of lye soap in boiling water.

- Sort things making three piles – one of white, one of colored, and one of rags and britches.

- Stir flour in cold water to smooth for starch and then thin down with boiling water.

- Rub dirty spots on board and then boil. Rub coloreds but don’t boil. Take white things out of kettle with broom handle, then rinse, blue and starch.

- Spread tea towels on grass. Hang old rags on fence.

- Pour rinse water in flower bed.

- Scrub privy seat and floor with soapy water.

- Turn tubs upside down. Put on clean dress, comb hair, brew up a tea, sit down a spell and count your blessings.

From Jasper National Park, they set out across the prairies – the home of the Chinook winds – and on to Edmonton. Then on to Calgary, back over the Rockies to Banff, down the Okanagan Valley, and back to Chelan. By now, in mid-June, summer was in full stride. Temperatures were well over 70°F and apples were rapidly swelling on the trees.

They were looking forward to setting up camp on Joe and Gloria Bennett’s orchard and staying in one place for more than a day or two. They had covered 8,265 miles since first leaving Los Angeles and were ready for a break. They set up camp in the pickers’ quarters and prepared themselves for four weeks of thinning apples.

The Bennett orchard was on the lake’s western side, just to the south of Twenty-Five Mile Creek State Park, facing south-east with a great view over the lake and steep hills under sparse pine and grassland rising behind. It was an idyllic spot and quite remote from the cosmopolitan cities of the West Coast. This was deepest rural America. The people were remarkably insular and un-worldly, and many were paranoid about the outside world. Joe’s parents, who still lived on the orchard, and who had developed it from bare land, were staunchly conservative Christians who were utterly convinced that the blacks and Jews were scheming to take all they had worked for. Joe once said to me some years later, that his father would have shot any man with a black skin or with a Jewish yarmulke (skull cap) on his head who ventured onto his property. I believed him after seeing the bunker below his house with enough food to feed his wider family for a year and an armoury of around 50 weapons.

Joe and Gloria too, were deeply religious people, but they were less rabid in their political views. Joe had for years harboured ambitions to sail the world in a yacht, so he was convinced that Mum and Dad had been sent to him by God to inspire him, and to give him the courage to make it happen. While I’m sure he never achieved this ambition, by the time Karen and I got to Chelan in 1979, he had bought a 38-foot yacht, shipped it to Chelan, and was sailing it up and down the lake.

For all their paranoia and stubbornly insular attitudes, they were wonderful hosts and employers to Mum, Dad, and Pip. In keeping with his view that they were apostles sent to inspire him, Joe was always attentive to their needs. He took them on trips up the lake to Stahekin in his fizz boat, took them fishing and water skiing (at least for Pip), and ensured that they had all they needed while they were there.

After four weeks of thinning apples, they were on the road again, heading south to Yellowstone, on to Denver, and back over the Rockies to Palisade, where they stopped again – this time to pick peaches. They found work with Lindy Granat and Theo Eversol, neighbouring orchardists who lived just out of the township of Palisade, a stone’s throw from the Colorado River. They picked peaches and pears initially, but ultimately worked in Theo’s peach pack-house. Karen and I were here too in 1979, so we got to know the Granats and Eversols well. Lindy had largely retired by the time we arrived, but he was an absolute delight. A slow mid-western drawl masked a sharp intellect. He was curious about people and was endlessly hospitable and friendly. He took Mum, Dad and Pip on tours around the region and introduced them to members of his community. I recall that he only ever wore sleeveless bib overalls – new, very clean and pressed if going to town; old, mended and threadbare if he was out on the orchard; but only ever overalls.

Likewise, Theo was a wonderful host, ensuring they were comfortable and had all they needed. Like so many in the Rockies, he and his neighbours lived simple lives, they were deeply religious and lived in much better-connected communities than in the larger metropolitan cities on the West Coast. These communities were, though, deeply conservative and mistrustful of outside influences. For most, their horizons were limited to the local county and what went on at the state level was often mistrusted. What went on at the Federal level was very remote and disconnected from their lives. There was little or no awareness of a world beyond the United States. However, this was not true of the Granats and Eversols who were highly curious about these strangers from the South Pacific. They were to provide a wonderful window into the functioning of this small rural Colorado community. Mum records the observations of a local who’d been off with a group to the State Parliament in Denver to “…learn all about Government you know, and there was this guy who moved to legalise marijuana, and another moved to legalising prostitution. Others said it wasn’t allowed by the Bible and there was lots a hoot’n and holler’n and one guy threatened to punch another in the nose. Why, it was a real freak-out!”

Another story Mum often told was about the peaches themselves. Mostly, they came off the tree quite hard, but occasionally, a tree-ripened one would come across the conveyor belt. Usually, these would go out to the “Cull Truck,” but Dad couldn’t face the loss of such perfect fruit, so he would take those he found and line them up along a beam in the packhouse. He would progressively eat through these throughout the day and seemed never to get stumped. Some years later, I had the same problem: they were fruit like I had never eaten before and have never since.

While useful (probably essential) for putting money in the kitty, these stops were wonderful opportunities to connect with people in more than a cursory way and for them to get to know real rural America. They did this, and these occasions would always play a big part in their narrative about their travels.

By early September, they were on the road again after five weeks in Palisade, this time, going back over the Rockies to Denver where Pip caught a flight out to London. Mum and Dad, feeling a little alone without their travelling mate, headed north into Wyoming past the Wind River Range and through the Grand Teton National Park. Mum describes in her journal, the stunning country with timber rail fences, fat cattle, beautiful horses, crystal clear rivers, and always the dramatic peaks of the Teton Range dominating the view.

They followed the Oregon Trail through Idaho, down the Snake River to Boise, and then north-west across the Blue Mountains at Meacham Meadows (Malcolm’s family must have been early travellers on the Oregon Trail), into Washington, and back to Bennett’s orchard in Chelan.

Nothing had changed in the six weeks they’d been away, apart from Mitzi the pup and the apples being bigger. They settled into their old cabin as if they’d never been away. They had another six weeks here, picking apples, walking in the hills, boating on the lake and keeping good company with a rag-tag bunch of pickers who descended on the orchard for the harvest. Mum’s journal records vignettes of the people and of the experiences they had – Mac from Nebraska with his observations on the comings and goings of people under his bed (from dust to dust), Garry ‘the languid one’, who said he “… talked very knowledgeable most times but it was really only shit. Only God knows it all; we can only learn the hard way”. Another whose uncle was an ex-army Colonel “…who imported all sorts of garbage from Japan and drank to make his life bearable”. There were chipmunks, snakes eating mice, coyote pups, and stories about the youth of Chelan.

Like Palisade, this place and its people were to make a deep impression on them and remain with them for the rest of their lives. More so than Palisade, the landscape appealed to them both. Vancouver Island would probably have pipped Chelan for the top spot for Dad, simply because of the proximity to the sea, but Chelan would have been a close second. For Mum, it would have been a toss-up between California’s rolling grasslands and oak forests with its fat cattle and Chelan. California would probably have won simply because winter would have been warmer. However, it would be the people they met and the friends they made that would make the more indelible mark. It seemed that they too, left quite a mark on those they left behind. Mum’s journal records several dinners in the week before they left with friends they’d made.

So, with some sadness, they loaded up Bessy and headed south on the 2nd of November. Autumn colours were vibrant, vast skeins of Canada geese were heading south overhead, and winter was already beginning to creep in from the north. Snow was on the tops and the cold crept in early in the evening, forcing them into the van with their hot water bottles. They went back through Oregon and Idaho to Boise, then into the northern Utah wheat country, which Mum observed ‘…must take religious fervour or some like sustaining force to keep people on that land.’ Salt Lake City was not much better, just dominated by vast steel works and smog. On south through sheep country to the Virgin River (where the Utah grimness gave way to blooming marigolds, fine mobs of cattle and lovely horses) and down into Arizona to Flagstaff.

The chill of winter was still present, but it was much milder, and here they met some Alberta farmers among the throng that migrates south in their RVs for the winter.

On south still through New Mexico to Albuquerque and into Texas. Swinging east then, across the Texas Panhandle and into Oklahoma, then Arkansas where the land still showed some signs that it had not fully recovered from the dust bowl era of the 1930’s and 1940’s. There was, though, lots of cotton and rice grown near to the Mississippi River – that ‘wide muddy creek’ – which they crossed at Memphis in Tennessee. On east through Tennessee to Nashville – Music City USA; ‘..a dreary old town, very down at heel’, but they didn’t stop long enough to listen to the music. Through the Great Smoky Mountains and down to Spartanburg in South Carolina, and out to the Atlantic Coast at Charleston. They were quite taken with this old town with its beautiful old houses. They were also hugely impressed with the bayou country as they went south. Mum suddenly became enthusiastic about a sailing trip through the Inland Waterway which Dad had talked of for years. Savannah in Coastal Georgia did not compare well with Charleston and Beaufort, but it was nice enough for Mum to still contemplate an Inland Waterway cruise.

It was perhaps a shame that they had to rush across these southern states, that they didn’t tarry a while and ‘listen to the music’. Mum had long had a fascination for the South. She had read extensively about its culture and its history – William Faulkner, Truman Capote, John Steinbeck, Harper Lee, and Carson McCullers being just a few. The landscapes were indeed not a match for the West, but she would have delighted in the culture had they given themselves some time. As it was, they were hell bent on catching up with Kay and Malcolm and seeing Scott, their first grandchild, and I suspect too, that they were ready to go home. So, they pushed on.

Into Florida, they were surprised at how much more natural wetland and open country there was, at least in the north. Saint Augustine was a particular favourite with several cruising boats holed up there for the winter. Further south, beyond Fort Lauderdale, it was all substantial grand mansions; ‘…tasteful and attractive, but I found myself like Ticka, saying constantly, oh my God, they’re singularly lacking in colour!’

By now, though, they had moved out of travel mode and were fully exercised in mind about getting their worldly goods packed up and shipped off home, the van sold, and tickets purchased for South Africa. This must have been a stressful time because nothing seemed to go well. Arranging to ship their gear home proved a nightmare. It was ruinously expensive, problematic at every step, and ultimately useless, as the stuff never arrived in New Zealand. Equally, they couldn’t get any offers for Bessy that were anywhere near its value. No doubt the Miami car sharks knew instantly that they were flying out soon and had no room to negotiate. In the end, they sold it for a song.

November 30, 1974, just before midnight at the Miami Airport; ‘…an airport of awesome modernity, its only memorable feature, the line-up of Latin bucks on chairs outside the lady’s loo.’ They boarded their plane and were soon to leave the United States, never to return. They had grown to love this vast country, with its expansive and beautiful landscapes, its hugely diverse and endlessly fascinating people, and its contradictions. At once a vibrant, energetic and innovative nation that befits its dominance in the World’s economy, but also populated outside its main centres at least, by an insular, divided and paranoid people struggling to cope with the changes that were happening around them and over which they had no control.

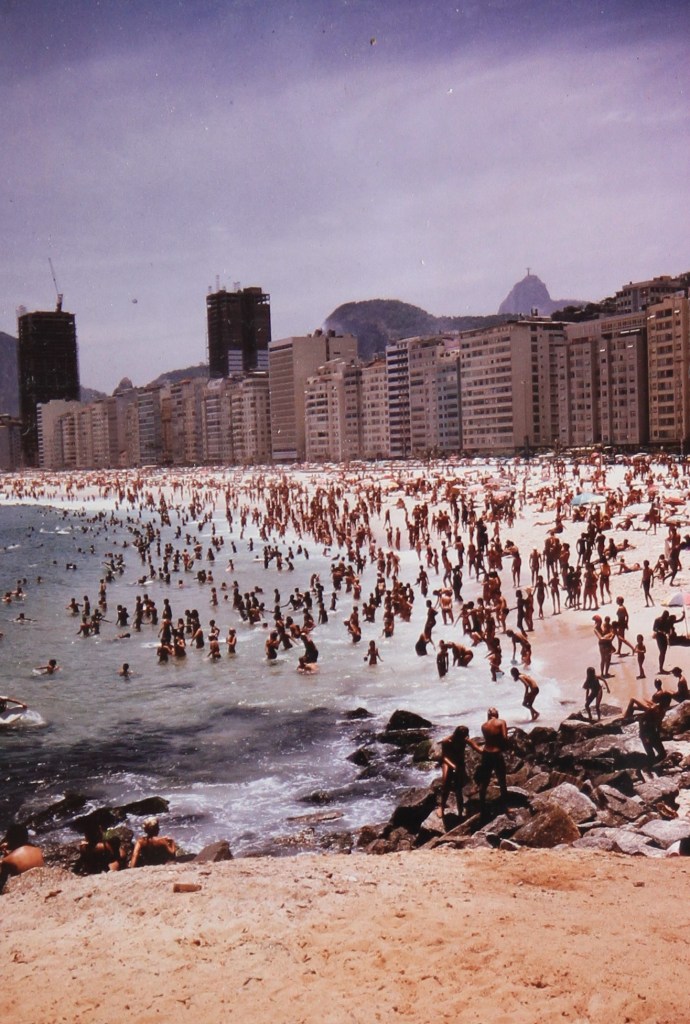

They had a couple of days’ stopover in Rio de Janeiro—another cauldron of diversity and difference and a wonderful opportunity for people-watching. Then, they went on to Johannesburg and East London, where they were met by Kay and Malcolm and their number one grandchild, Scott.

As happened whenever they stopped, the journal went silent as soon as they arrived in East London, but I can only imagine how great it would have been to catch up with family again. They had not seen Kay and Malcolm since soon after their marriage in December 1972 and of course, they had never met Scott. They had read all Kay’s wonderfully descriptive and detailed letters, but these would have been poor substitutes for the reality. They spent Christmas here with Kay, Malcolm and family, and then in early January, they all (Mum, Dad, Kay, Malcolm and Scott) set off for the Transkei where Malcolm had grown up, en route to Pretoria where Mum and Dad were to leave for home.

The journal starts up again at this point and records a landscape and people that would have been utterly foreign to them. Again, Mum delights in the differentness.

And so ended an adventure that lasted for over a year and a half, and which would both inspire them and sustain them for years to come.

The Second Pacific Cruise

After their first Pacific cruise, Dad would likely have been happy to spend his remaining sailing days exploring the coast of New Zealand, perhaps just confined to the north-east coast of the North Island. Mum, however, had other ideas.

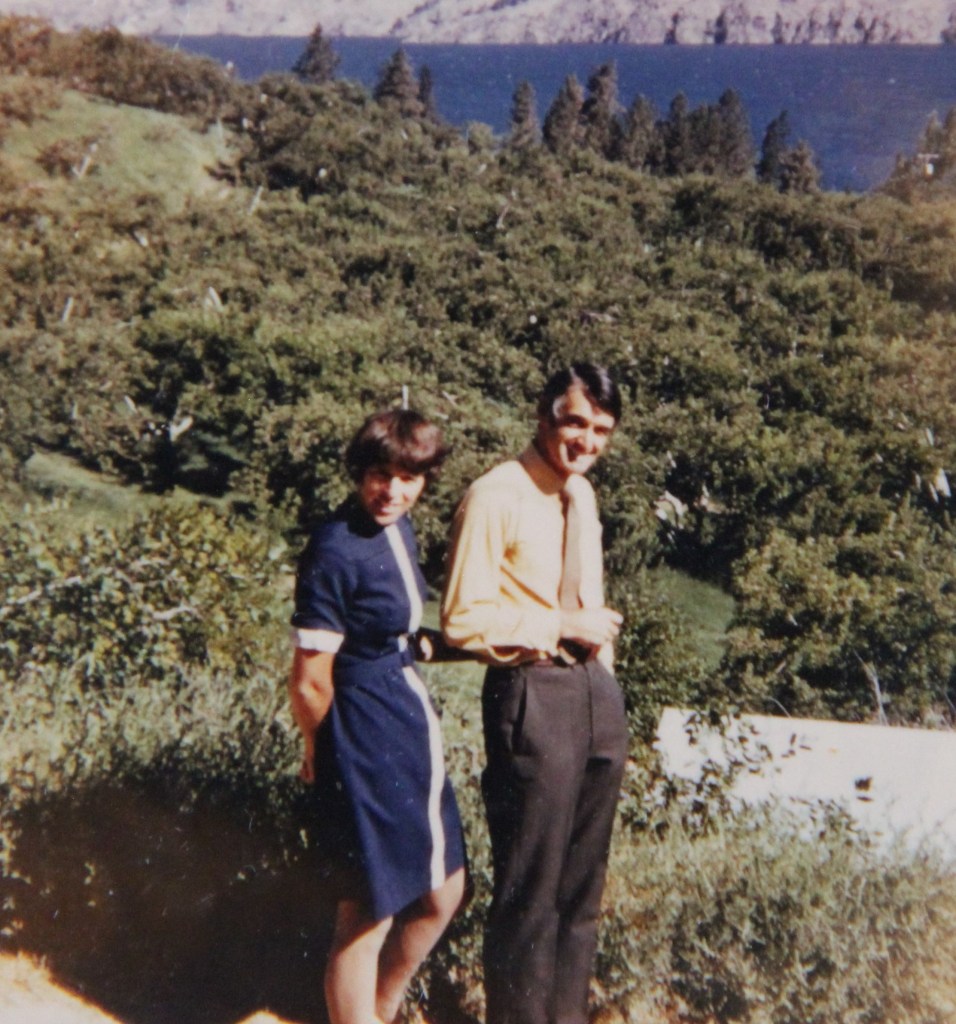

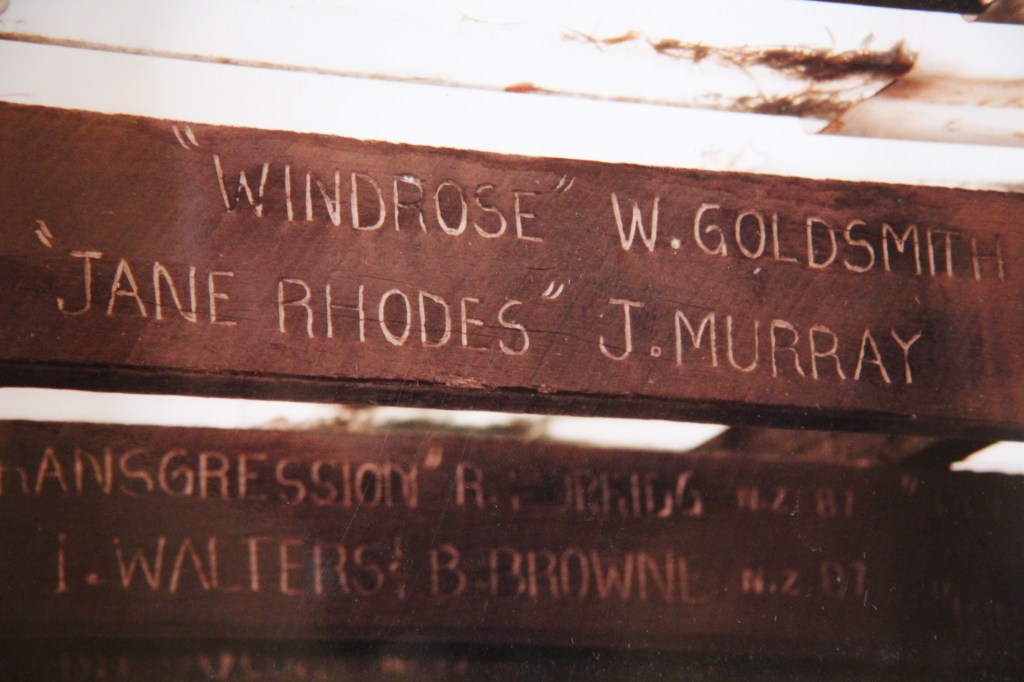

She worked away at Dad and eventually he agreed to a second Pacific cruise – going back to the Society Islands, but this time, swinging west through Tonga to Fiji. He set about finding a suitable boat. This came in the form of a yacht called Jane Rhodes, a 36-foot cutter built in 1968 by Jorgensen and Son’s in Waikawa Bay. She was built of 1.25-inch (3.2cm) single skin kauri and with a rounded Scandinavian stern. Like Cecilene, she had a full keel, which provided more stability at sea than the more modern fin-keeled boats. She was as solid as a rock, a little ‘wet’ when hard on the wind, but she could sail. She was in Nelson when they bought her in January 1984, so Mum, Dad and Pip sailed her north in February of that year. Dad wrote a feature article for the Sea Spray magazine on this trip, published in July 1984. The title, ‘Nelson to Sandspit and then…?’ speaks volumes about where Dad was in his head about another ocean cruise.

Dad had never liked Leigh Harbour as a place to keep a boat as it was badly exposed to the south-east. This was a fair point, as several storms had driven boats off their moorings and piled them up at the head of the bay.

So, despite the inconvenience of travel between home and boat, he put Jane Rhodes on a swing mooring at Sandspit. She was in good shape, but there was still much to do to bring her up to an offshore rating. He did this over the next three years on weekends and at increasingly regular moments, he could sneak away from the shoe store.

There were many shake-down cruises around the Hauraki Gulf, Great Barrier and the Bay of Islands, some of which they used to induct Scott, Gilly and Richard into a life of cruising. Once, just as they set off on their way north to the Bay of Islands, the engine died as they were off Cape Rodney. It proved not to be something that could be fixed with epoxy resin or the like and would need some significant professional attention. Mum, who had limited leave from her work, was gutted. Dad, however, wasn’t ready to give up and suggested they go anyway – under sail. “How hard could it be?” They spent the next three weeks sailing up the coast, around the Bay of Islands, and back to Sandspit without so much as a hitch. Mum, who thought marine diesel engines were noisy and smelly, was delighted.

By April 1987, Jane Rhodes was fit to go, they had sold the shop and Mum had quit her job. After endless trips to Sandspit in the old van, Dad had stowed away all they needed for the voyage – but for their French visas. They farmed out the cat – Deuteronomy Boggs – let the house and set off for Auckland where they waited for their visas. It was another two weeks before they finally got away, but on the 9th of May, they slipped their mooring lines from Admiralty Steps and set off down the Waitemata Harbour. Raywin Miller (their daughter-in-law Jude’s sister) had joined them as crew.

For the next several days, winds, when there were some, were all over the compass. Progress was slow, and Mum’s seasickness persisted beyond the first few days despite her use of the patches behind her ear. Her journal entries are still determinedly cheerful, however, and she still seemed to greatly enjoy eating their way through the fresh food.

Unlike their first trip, they kept watch throughout the night this time, or at least someone sat tucked under the dodger and periodically scanned the horizon. “Fred, the self-steering system, mostly did his job and was appreciated by the crew. He could keep a course and didn’t mind the odd bucket of seawater that periodically got dumped into the cockpit.”

Twenty days on, they had covered little more than 1,500 nautical miles. The wind had finally come in, but from the south-east and with gathering strength. After four days of lying ahull in gale-force south-easterlies they had a vote on whether they should wait it out and persevere on their course to Papeete or bear away north and head for Rarotonga. It was two-to-one for Rarotonga – Mum being hugely reluctant to give up her dream of returning to Tahiti.

Once off the wind, Jane Rhodes immediately settled into an easier gate, the temperature rose quickly, and things began to dry out. The Skipper, convinced they’d done the right thing, sat in the cockpit singing ‘We are Sailing’ as they rocketed under a pocket handkerchief of a headsail, approaching eight knots. As a foil for her ‘Slough of Despond’, Mum fed the crew pasta and Italian sauce (the Skipper hated pasta), listened to Dire Straits and read Alan Moorhead’s ‘The White Nile’ for the umpteenth time, concluding that the travails of 1860s African explorers made theirs pale into insignificance.

At 2:00am the next morning, Raywin smelt land, so they hove-to and waited for the dawn. Right on cue as dawn broke, Mangaia appeared out of the mist. They sailed close by the outer reef, smelled the pineapples, and headed on to Rarotonga.

One of the challenges of ocean cruising is to conserve water. I don’t know how much water Jane Rhodes carried, but it would not have been more than 300 litres. Mum and Dad had long perfected the art of a ‘flouse’, as Mum called it – a wash with a cup of water and a flannel, and they never washed clothes unless they could gather more water from the sky. As they ran north toward Rarotonga, there were many squalls that passed over them and they made several attempts to capture some rainwater, but with only limited success. The washing would have to wait.

At the commercial port of Avatiu, the Harbour Master would not let them tie up and insisted that they go on to the tiny lagoon in front of Trader Jacks – sadly not functioning at the time, having recently been destroyed by a hurricane. They got in – just, but bounced on the bottom at low tide and threatened to beat up against the coral breakwater when the wind got up. “Damn it; we’re going back to the main harbour”, Father’s declaration at 4:00am as the northerly strengthened. They tied up beside a sizeable Danish yacht, ‘Nordkaperew’, the only other yacht in the harbour, and waited for the argument with the Harbour Master. He never came and the Island Trader skipper adroitly manoeuvred around them, completely unperturbed.

Between washing clothes, restocking supplies, and cleaning up the boat, they spent the next week soaking up the Rarotongan culture and doing the tourist thing. Visitors came and went, as yachts were not common in Rarotonga in those days, and they spent some time sharing stories with their Danish neighbours.

One visitor, a Kiwi yachtie who was there with his non-boating wife, asked to listen to the WWVH time signals so he could practice his skills with a sextant. For most navigators of the time, having an exact time was crucial for finding your longitude, and WWVH could provide that. This American short wave radio transmission service provided time signals every minute and data on significant weather systems in the Pacific on the hour. Satellite navigation systems were beginning to be used in cruising vessels by 1987, but they were ruinously expensive and not particularly reliable. However, on this trip, Dad would have given his left arm for one several times, although he was not quite ready to give away his sextant.

They said their farewells to Raywin who flew on to Papeete, made some final preparations for sea and set off north toward Vava’u.

They had enjoyed their time in Rarotonga, its relaxed and hospitable people, the smells of frangipani, and everything clean and tidy. There were no mosquitoes, but there were no birds either besides minahs. There were masses of dogs—always friendly and rarely barking – and it was mostly warm. However, it was not quite warm enough for Mum.

The voyage north to Vava’u was relatively uneventful. The Mate spent much of the first few days battling seasickness. It was overcast, cold and blowing like hell. Often sailing with nothing but the radar reflectors and the ratlins to drive them, they made slow progress. The Skipper became exceedingly nervous about navigating solely on dead-reckoning, particularly as there was one of those nasty notations on the chart which read ‘breakers reported 1945’. However, the weather cleared, the wind switched to the south-east and they romped along under clear skies. The Mate got ‘logged’ by the Skipper for filling the meths-bottle, inside the requisite distance from the Primus stove, and they listened to the All Blacks play the French in the inaugural Rugby World Cup (29-9 to the AB’s) as they sailed past Niue.

Eleven days after leaving Rarotonga and after several days of rain and overcast, dead-reckoning and radio direction finding (using a transistor radio) suggested to Dad that they were somewhere near Vava’u. So, they hove-to through the night to await a good fix on their position in the morning. As it was, they could have sailed on, but he wasn’t to know that. He later wrote ‘I sat on watch in perfect sailing conditions thinking a Sat. Nav. might not be such a bad idea.’

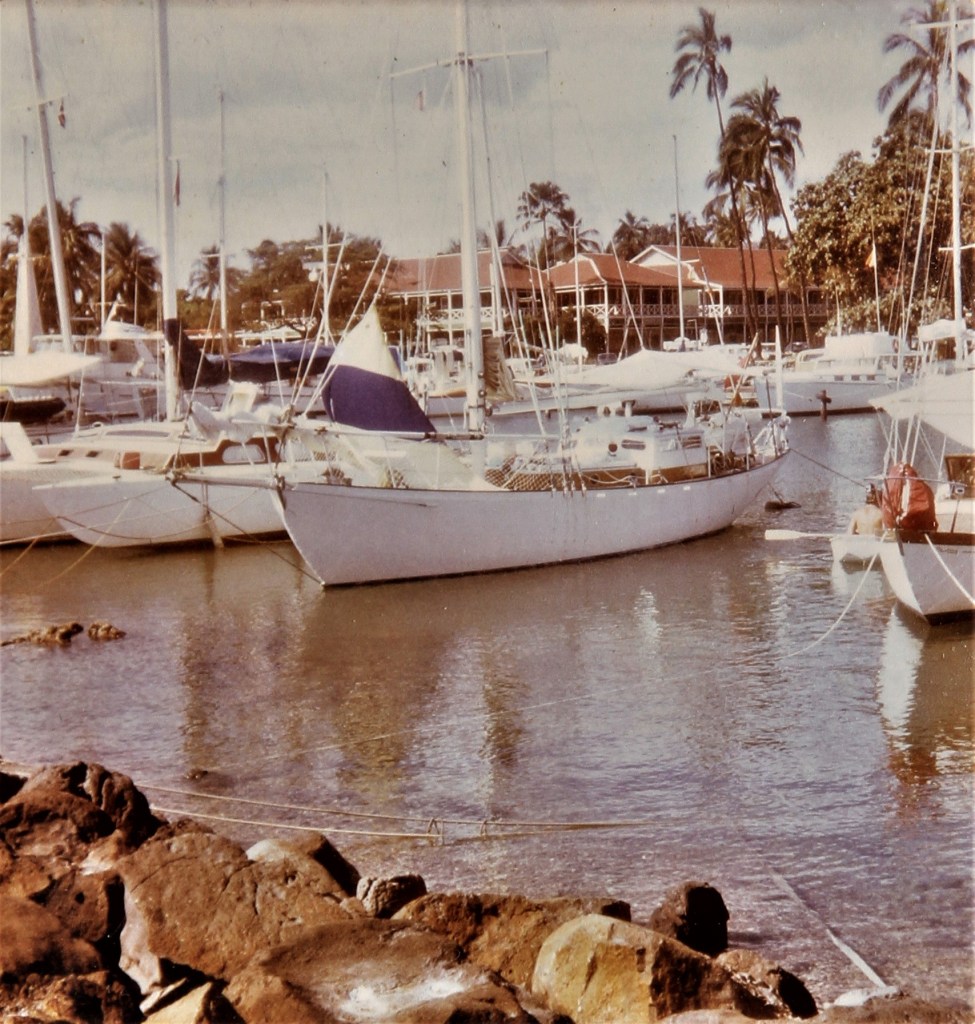

Late the following afternoon, they tied up to a jetty in Neiafu just as the King of Tonga set out to go sailing with much pomp and ceremony, accompanied by a flotilla of canoes.

The following month was a social whirl. They were not allowed to leave their anchorage at Niefu in the run-up to the King’s birthday celebrations on the 4th of July, but this hardly seemed to matter. Fifty other yachts were at anchor with them, some of whom had also diverted from a course to Tahiti in terrible weather. The fifty lots of crew seemed to spend their days on each other’s boats, in the markets and wandering the town. They all gathered in the evenings in the Paradise Hotel for ‘Happy Hour’ and stayed there, often to the wee small hours of the morning, dancing, singing and talking boats and cruising. These sessions were occasionally interrupted by local King’s birthday events to which they all descended en masse. On the day before the birthday itself, they all participated in the inaugural Neiafu visitors yacht race.

Mum’s journal describes some of the many people they met. Sue and husband from Illinois who went for a holiday in Miami, saw some boats and thought, why not, and never went home; Burt Woollacott’s daughter Madge and partner Tom who spent 8 months of the year either cruising or campervanning around the world; ‘an old goat’ who, after his wife left him and knowing nothing about boats, sailed down the French canals, across the Atlantic and down to New Zealand; an engineer – ‘a handsome Israeli’ enroute to Alaska; and Kay and Mark on their yacht ‘Shadowfox’.

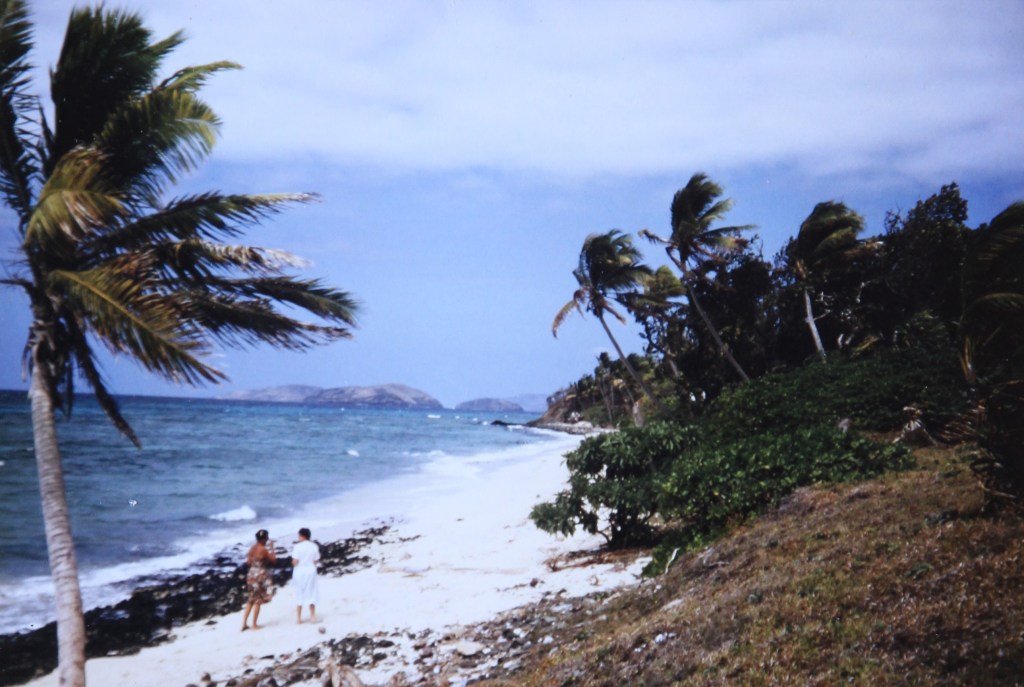

They were finally able to leave their anchorage on the 10th of July. They ventured out with other boats to Port Maurelle where they all barbecued on ‘a glorious white sandy beach’. Mum enthuses over the blue water ‘like liquid crystal’, the delicate corals and fish of every imaginable colour. The water is too cold for her though, so she leans over the side of the dinghy with her mask on.

Pip, Lynne and a three-and-a-half-month-old Sam arrived on the 14th of July, and despite the late hour, they had no difficulty finding Mum and Dad as every foreigner in town seems to know who they were and where they could be found. Gramma and Grampa were delighted to see their number nine grandchild. Over the next seventeen days, Grampa, recovering from a cold, would get many opportunities to practice his childcare skills. Mum, Lynne and Pip went off to explore the island around Niefu and later, when all five ventured out to the islands to the east, Dad would often be left boat and baby watching. Nuapapu was Mum’s favourite spot of the outer islands, but for her, every island seemed like it had come out of a travel brochure.

Come early August, many of their neighbours were heading east to Fiji, but the weather was still volatile – and way colder than Mum would have liked. They dallied around Neiafu for several more days, but finally and a little reluctantly, as they had grown to love this spot, they set off to sea.

Mum reflected on Vava’u as it slowly sank into the Pacific behind them. A cheerful and dignified people with a nice sense of proportion. Delightful children with open and completely unaffected curiosity; housewives outside the most minimal houses, painstakingly sweeping leaves off their lawns; and exuberant vegetation everywhere – frangipani, poinsettia, bougainvillea and shore hibiscus growing right down to the water’s edge. And the sea, that deep aquamarine blue with its corals and myriad fish, and those glaring white beaches.

Of Vava’u, Dad wrote:

‘Tonga, a feudal kingdom with a developing bureaucracy. Poor people who can walk tall. Elderly folk who have dignity and mana. Church schools churning out crops of fine young, educated people with few places to go. Its own country, washed and inevitably influenced by external currents.’

For them both, it was a wonderful social experience. The ocean cruising community was populated with a great array of characters and interesting people, but the one thing they all had in common was their love of ocean cruising. They would both miss it.

Two days later, they found Ongea just where it should be. The weather had been awful, but the wind was behind them and there was just enough sun to get a sight or two to quell the Skipper’s anxiousness.

A day after seeing Ongea, they were standing off Suva. The entrance is not easy to find at the best of times, but with a strong south-easterly putting them on a lee shore, a strong westerly setting current and low cloud, the Skipper was very nervous. ‘Sat nav climbed ten places in the priority list’ he later wrote. A ship, coming up behind them, showed them the way through the passage, but not before they had some anxious moments as they clawed off the reef into the wind, having heard it before seeing it.

It was mid-August 1987 and the political situation in Fiji was still very tense after the first coup d’etat in May. They expected to see more military presence in the streets and more restrictions on their movement, but life seemed unaffected. They wandered the markets and enjoyed the hospitality of the Suva Yacht Club for a week, and after picking up their next crew mate – Ruth Munro, an ex-workmate of Mum’s, they headed south to the Astrolabe Reef and the Kadavu group of Islands.

Dad later wrote of their first visit to a small Fiji island – Ndravani – and his first time offering sevu sevu (a gift) to the local chief. This is traditionally some kava root which one lays on the woven pandanus mat in front of the chief and at the same time saying “noqu sevu sevu gor”. If he picks it up, you’re free to play in their backyard. Presumably if he doesn’t, you must pack up and go. On this visit and all subsequent visits to other islands, he would add to the gift of kava root, books and barley sugars for the kids, instant noodles and Fiji tobacco. These gifts were always accepted, so they would share in the kava drinking ceremony and chat with the gathering families, often through the teenagers who would act as interpreters.

The weather had finally settled, and the temperature reached something near Mum’s comfort zone. They island-hopped down the chain, calling in at each village as they went. Mum describes the people as open, welcoming, and well-informed about the world beyond their village. They made some real connections with the locals here and Mum was to maintain contact with some of them by letter for some years after.

The islands were classic tropical Fiji – surrounded by bright sparkling water, good coral, heaps of fish and white sandy beaches. The land, though, was generally burnt to a crisp and largely treeless except for the coastal fringe. This was a source of great frustration for them both as they sailed west around Viti Levu and up the Yasawa chain. Smoking fires everywhere and almost no standing forest. They never could get a satisfactory explanation for why this was done, but Google maps today suggests that the practice has largely stopped, and some good reversion is occurring.

After a short stop at Saweni Beach and Lautoka to re-supply, they went onto Malola Lailai and the Musket Cove Yacht Club where the cruising community gathered in mass. Dad was in his element. There was much socialising at Dick’s Bar, Plantation Resort and on other boats, Mum and Ruth learned to windsurf, and they caught up with Elizabeth Farley, who was holidaying in Fiji at the time.

As they returned to Lautoka where Ruth was to leave them, radio reports began to come in of fires and shootings in Suva in the run-up to the second coup d’etat. There were noises of service shutdowns including buses and taxis, but life seemed to continue as usual around Lautoka. There was though, much talk in the streets about what was happening. Many ethnic Fijians were quite vocal in their support for Rabuka and critical of the ethnic Indian influence and control on their economy. The ethnic Indians for their part, were a little more circumspect. This attitude was to be repeated often when they were later in the Yasawas, when Rabuka declared a Fijian republic. Mum records all this with some frustration at the simplistic attitudes which she felt would badly hurt the Fiji economy.

Just as another friend, Jennifer Kirker, was to fly in, Rabuka and his military forces conducted the second coup d’etat, on the 25th September. He ordered a complete shutdown and curfew over the whole country. This included all shops, buses and taxis, but apparently not incoming flights from New Zealand. Jennifer duly arrived and somehow, they managed to persuade a taxi driver to take Dad to the airport in Nadi, collect her and bring her back to the boat. It seems that the attractions of a good fair overcame his fear of the military regime.

Despite their spirits having been dampened by a robbery while they were ashore shopping – losing some cash and equipment – they remained enthusiastic about the prospects for their next leg of their trip, out along the Mannanusas and Yasawa group of islands. They stopped first at Malola Lailai to induct Jennifer into the cruising community and set out to Yanuya Island. The following two weeks, they slowly made their way north as far as Soso Bay on Naviti Island. They stopped at villages on the way, drinking cava and exchanging gifts. They also spent several days at uninhabited islands, which today Google suggests are now occupied by high-end resorts. Their days began very early with a skinny dip, followed by the obligatory morning cup of tea. They then snorkeled, beachcombed and pottered about, and in the evenings, they watched the sun sink into the sea with a gin in hand. Mum was in her element.

It was now the middle of October and many of their cruising colleagues were beginning to drift off south to New Zealand. They reluctantly headed south again, first to Lautoka to re-supply, then to Musket Cove before finally heading home on the 24th of October. Dad describes the return trip as the easiest leg of their journey. They dropped anchor in Lagoon Bay on Motuarohia Island in the Bay of Islands at midnight on the 7th of November. ‘The weather had cleared, the near-full moon was out…, the land smelt good after the rain, and as an old ewe bleated nearby, we slept.’

The United Kingdom

Mum had always hankered to go to Europe. Various family members had travelled there throughout her childhood, her mother and uncle had toured Europe extensively in the late 1950s, and all her children had spent time there during their OE. She had also read much about it throughout her life, so it was a place she felt she had to see.

As she began her planning in 1988, Dad dug in his toes. “You can go if you want, but I’m not going!” So, she took him at his word and began to plan a trip alone. This would involve flying to London, working for a while, and then travelling through the UK and Europe. I wasn’t aware of this at the time, but it appears from her diaries, that at some point, Dad had agreed to join her after she had worked for some six months. It is unclear whether this agreement included touring Europe, but by the time he arrived in London, the plan was confined to touring the UK by camper.

Mum left for Singapore on the 8th March 1989, ‘masking the tears by making a meal out of filling in the departure card’ She had a couple of days in Singapore, wandering the city, offering her shower to a young Aussie reporter and together drinking pink gins in the Raffles Hotel – ‘just about as good and my man’s’ – and taking a quick trip into Malaysia. The latter she described as like walking over a short bridge from Auckland into Fiji, albeit with incredibly tight border controls. She even plucked up the courage to shop for clothes, buying some peacock blue pants and a navy top. Wearing these and an orchard in her hair as she boarded her flight to London, a young Malaysian woman said, “Oh, you do look pretty”. Her confidence boosted, she relaxed into the long flight and slept.

Unlike many new arrivals at Heathrow, she found the London morning warm and sunny. Her bus was waiting where it was supposed to be, and it dropped her right off outside her hotel, the Park Court, in Kensington.

As she set out the following day to orient herself in the city, a young Aussie woman asked if she could join her (Mum thought she looked little more than a kid but she was in fact, a qualified doctor with two years’ experience. She thought Mum looked like she knew where she was going). They spent the next two days walking the streets and parks of London together, visiting some of the more famous features including The National Gallery, Piccadilly Circus, Buckingham Palace and Kensington Park. The Irish Guards brass band brought forth floods of tears (brass bands always did that to her), but ‘their horses were dog tucker’. Everything seemed strangely familiar but at the same time, new and fascinating.

She moved into a bedsit in Ealing (where Joan and Ian Stewart had once stayed) and began looking for work. She clearly didn’t have her heart in it as she often ended up in places like Kew Gardens, or exploring other interesting parts of London, but over the following days, she made an effort to check out ads at the employment agencies and to look at ‘Staff wanted’ notices at pubs. However, nothing inspired her and after a visit to a particularly unattractive pub in Richmond, she decided she was off pubs and began thinking about companion help.

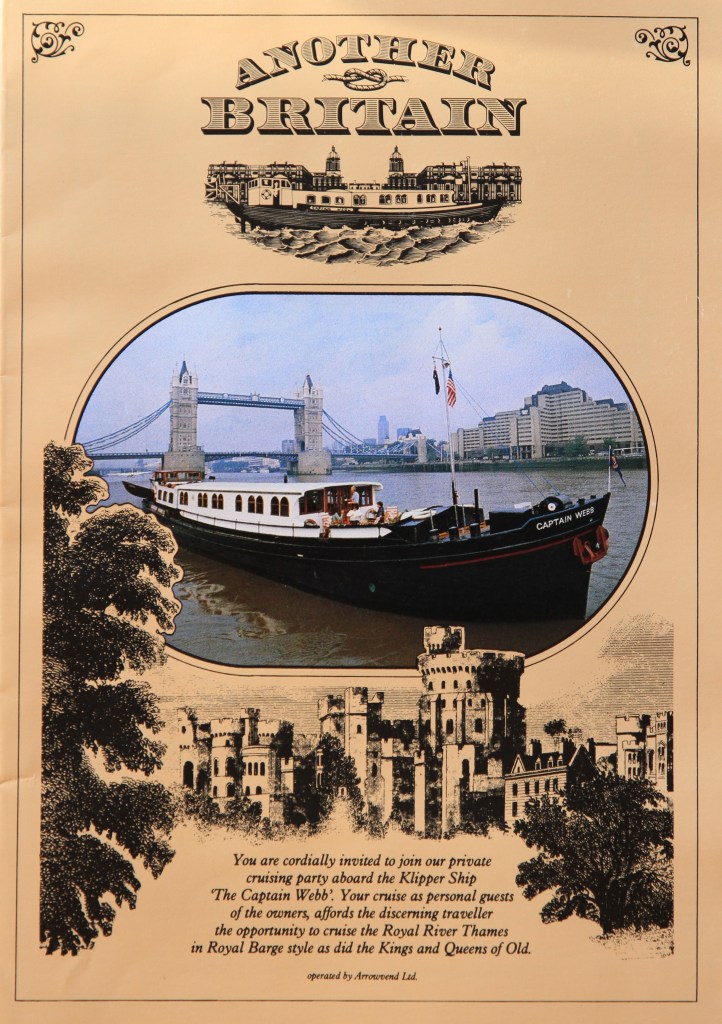

Some days later, after she’d been to visit Ham House with some friends and as they were walking along the canal towpath, she saw a particularly attractive river boat ‘with nice lines’, and on the gangplank, a list of prices for a tour including £500 for the whole boat. Below this, a sign read ‘Crew wanted’. On a whim, she went aboard and two days later, she was signed on as crew. This was the ‘Captain Webb’, a large and elegant barge that had been converted to accommodate and entertain guests. Her duties were to drive the barge, help manage its passage through the locks, do a little maintenance, and assist with the hosting of parties. It was a live-aboard in a comfortable, spacious cabin, and food was provided in the form of sumptuous leftovers.

The owners were Gaynor and Richard, and it was Richard who gave her the job. However, Gaynor was apparently the one in charge. Mum noted on first meeting her; ‘she looked and sounded like Victoria Wood, but she wasn’t nearly as funny – she’s a raving nutter!’ Despite her early damning assessment, they got each other’s measure and worked well together. Richard was not well, having recently been diagnosed with HIV AIDS, but this didn’t seem to prevent him from capably managing most things on board the barge.

Mum spent the next eight weeks travelling up and down the Thames and along London’s network of canals, picking up parties, wining and dining them as they cruised the canals, and returning them to their destinations. She often wondered why they travelled when a party was on board as the punters rarely noticed what they passed. However, she noticed, so it suited her fine.

The guests included wedding parties (‘the bride was delectable, but the groom and his sister got drunk and argumentative, and the Conservative MP was a perfect idiot!’), business ‘meetings’, friends’ groups, an American TV film crew, and ‘eleven Brazilian money shufflers of some sort’. All were well healed and generous with the tips, if not well behaved. The work wasn’t taxing, and she still had plenty of time to get out and explore London and visit people, including Jill and Colin Sargent who were living and working in London at the time. She was also able to take a couple of days for a trip to Bath where she had long wanted to see the Royal Crescent, a magnificent piece of Georgian architecture in the form of 30 terrace houses built in a sweeping crescent with a large lawn in front.

Not long after arriving in London, she began worrying about Dad, whose letters indicated that he was not coping well on his own, and the phone calls didn’t reassure her. She spent a fortune on these – up to £10.00 in a call – but she continued to worry. Meanwhile, back at home, Dad was sharing his anxieties with his kids and was finally persuaded to join her. When he told her he would be arriving in less than two weeks, she ‘…was all of a dither. What if he hates it all?’ Still, she was over the moon and began planning where to take him and what she would show him.

Mum finished her last day on the ‘Captain Webb‘ and on the 15th of May, she went out to Heathrow to meet Dad off the plane. ‘First on, so last off of course. He hove into view at last, oh joy and delight!’ Over the next few days, they travelled all over central London, going to all sorts of places she hadn’t intended to take him, and somehow missing the ones she had wanted to show him. None of this seemed to matter, however. He was very happy.

They bought a yellow 1973 VW camper at the Van Market for £1,950 and named it Karitane. They furnished it with essentials like a teapot, kettle, and two hot water bottles, and after some more exploration of London, they headed south to Tunbridge Wells, where they’d arranged to visit an agency specialising in companion help. This resulted in a week’s assignment for them both to care for an aging doctor in Tunbridge Wells.

This was followed by a month as cook and butler for ‘a one-hundred-year-old anachronism’, Lady Godber. She lived alone (but for her staff) in a large property called Cranesden just out of Mayfield. It was a classic upstairs, downstairs situation with four full time staff (two gardeners, a chauffeur come house manager, a cook and a butler), a part-time secretary, and six part-time nurses who worked a roster to provide nearly full-time care. It seemed that Mrs Godber could never keep cooks, (although a German woman had lasted nineteen years there and died on the job), so Mum struggled to meet Mrs Godber’s expectations. She always gave explicit instructions on what should be cooked for herself and her staff, but nothing seemed to quite meet her expectations – at least initially. Dad impressed immediately as a butler, and she was quite charmed by him. He did blot his copybook once early in their tenure when he tried to help her out of her chair – “I do not need help from my servants to stand, thank you!” – but this was soon forgotten. She was also quite taken by the idea that her butler and cook had owned several yachts and had sailed across the Pacific. She required a photo of the said yacht as evidence. When they left, she was quite sad to see them go, and they too, were sad to say goodbye. It had been a memorable experience with a remarkable old woman and her retinue of delightful servants.

Over the next two months, they leisurely explored the byways of England, Wales and Scotland, rarely travelling more than sixty miles in a day and often very much less. Campsites were easy to find. They were usually just paddocks opened up to campers by local farmers to help supplement their incomes. Finding the right one, however, was often a challenge as it had to have a good outlook and be within reach of a good walk. Most were very good, but there was much debate between them about the best they had visited.

They established a regular routine, always stopping in a pub for elevenses, eating lunch on the side of the road, and cooking their own dinner in the van. There were always long walks after dinner.

On leaving Lady Godber in Mayfield, they went south to Rye (‘narrow lanes, old shops and pubs, and reeking of smugglers and ancient goings on’). Then they swung west to Gosport and Portsmouth where they collected mail (‘Two letters from Kay. ‘A great daughter to mother one, two months old via London. Bless you Kay!’) and began exploring Britain’s maritime history. Further west in Fowey, Dad was delighted to see that his mentor and hero, Peter Pye (it was a toss-up between Pye, Wilson (of Antarctic), Mother Terisa, Whina Cooper and Earl Mount Batten – Pye won out) was well remembered in his home port yacht club.

Wales wasn’t quite what they had expected. A little less rugged and a more manicured landscape, although there were plenty of fat, prosperous looking sheep. The houses were all four square and uncompromising, except on the coast around New Quay. Here, London and Manchester retirees with fat cheques from houses sold back home, were buying up land on which to retire, and generating some considerable grumblings from local farmers.

Here, they contemplated the possibility of a ferry trip to Ireland but at £259 return, they felt they could make better use of their money.

Once away from the coast and in and around the Snowdonia National Park, the landscape was more rugged, with many narrow winding roads, lovely stone houses, ancient churches and clear rocky streams – the Wales of Mum’s imaginings.

They tarried in the Lake District for a while. There were some wonderful places to walk, and they had a campsite that competed for the top camping spot so far.

The Langdale Valley was a particular favourite. Their campsite near Chapel Stile provided acres of space, a magnificent view, and a river to wash clothes in.

‘Lovely spot to wash clothes with a boy fishing from a stone bridge beside me. It made me think of all the places I’d washed clothes in a river. It sure beats hell out of a laundromat!’

Keswick and Derwentwater were a very close second and provided perhaps the best campsite. The National Park was seething with climbers and other tourists. Mum remarked at how effectively the area soaked up people like blotting paper—you really didn’t notice them unless they were on the roads. Cars were everywhere, and the roads were simply not up to handling the volume.

As they entered Scotland, the weather got much colder. The clouds came down, and it began to rain. It remained this way all the way up the west coast of Scotland: dark and misty landscapes not dissimilar to the Otago of Mum’s childhood on a cold winter’s day. The buildings, too, were not dissimilar.

They went to an agricultural show at Ledaig, where they competed with the judges in picking the prize animals. They got it wrong every time—or was it the judges who got it wrong? Despite the agricultural show, the country around was amazingly empty of any livestock—cattle or sheep.

‘On Bonnie Prince Charlie’s Road to the Isles. Were he to have travelled it today, he would spend a few nights with no host, and he’d find scant few mutton chops. We saw scarcely a hoof between Fort William and Mallaig. Land clearances of this country is pretty well complete. What houses there are, are holiday jobs on the coast’

Out on Skye, the atmosphere was still dark and gloomy although green and attractive. They couldn’t quite see what sustained people other than fishing and fish farming, but Mum concluded that it was dreamer country, occupied by people who had fallen in love with the landscape. She had to admit though, it had its charms – green headland against a blue-grey sea and the Black Cuillen behind. She recalled as a child singing songs in school at Patearoa about the ‘Wild Cuillen’ and wondering what they were. ‘Well, here they are!’

South of Inverness, they entered the lands that kings of Scotland had gifted the early Murrays in exchange for their allegiance and for their efforts to suppress the local warlords. They visited Blair Castle at Blair Atholl and made some attempt to find where Ladywell might be. The castle looked in good shape and well visited, but Mum noted that the land around, though impressive, wouldn’t earn enough to pay the current Earl’s insurance bill.

After Edinburgh, they went southeast into East Lothian. When they saw a sign to Bothwell near Cranshaws. They suspected they might be in Murray country again, but they weren’t to know that just ten miles to the east, they would find Marygold where John, Jane, and their five sons and daughter had farmed in the early part of the nineteenth century. As it was, they went south to Duns where Mum suspected they might find some Aitchisons. There were indeed Aitchisons thereabouts but unbeknown to her, they had already passed through her ancestor’s country south of Edinburgh.

They later visited Foulden to the east of Duns, where they stopped to look at a graveyard for signs of Murrays but couldn’t find anything. However, in a churchyard the next day, they found several John Murrays, along with some Georges and Janes and even some Aitchisons. Some of these may well have been ancestors’ graves, as John Murray and Jane Hunter were both born here, and several preceding generations of Murrays had lived there.

In commenting on the country Mum wrote:

‘We stopped there (in Foulden) to have lunch and looked over the rain-soaked farmlands of some affluence, the sort of land that must always have been blessed. Only the pressure of too many family members could ever have moved people off these acres.’

Back in England, the rain stopped, the clouds lifted, and the temperature rose several degrees. They meandered down the country through beautiful English countryside with many old castles; stone walls, bridges and viaducts; and carefully manicured farmland that seemed to get better as they travelled south.

They set up at the van market in London and put ‘Karitane’ up for sale. As Dad sat in the van waiting for buyers, Mum went back into central London, ostensibly to take some gear to Mrs Jenkins’ Ealing bedsit, but she spent most of the day exploring new parts of London. She also caught up with the ‘Captain Webb’ crew. Richard had disappeared some two months before and had not been seen since, but the rest of the crew were still there and carrying on with the business, presumably under Gaynor’s careful eye.

When she got back, Dad had made a good sale to an Aussie couple, so they packed up their gear, carefully pointed out ‘Karitane’s’ idiosyncrasies to the new owners, and, with help from Jill and Colin, who came to collect them, set themselves up in Mrs Jenkin’s Ealing bedsit for the last two weeks.

During those two weeks, Mum must have walked every street in London, revisiting some of her favourite haunts and ticking off a long list of places she felt she must see. Dad joined her on many of these forays but as he’d had a tummy bug, he mostly left her to explore alone. He did, though, join her on a day trip to Oxford, went with her to Greenwich and to the Tower of London, and saw a display of the Queen’s Guards (this time the horses were magnificent). On September the 7th, their last day in the United Kingdom, as they were making their way to Victoria Station en route to Gatwick (like old pros), Mum wrote, ‘B very tearful about leaving dear old Britain. I can’t imagine that I will see it again. It’s somewhat of a puzzle why such a grubby and rubbishy old city can be such a pleasurable place to be in.’

Leave a comment